John McGowan gives a quick psychological tour of some coming-of-age classics

Our term is up and running in Tunbridge Wells and our Clinical Psychology doctorate course has recently welcomed a new group. When our students start we don’t plunge them instantly into the world of mental health, but instead spend a few weeks thinking about the different phases of life. What make us who we are? What helps or hurts us as we develop? What are the challenges of growing older? We do sometimes write about films on this blog which prompted me to reflect on which are the most psychologically acute movies about growing up? Which ones illustrate, maybe without even realising it, psychological theories of development? Which ones make you cringe with recognition? Here is my top ten.

10.The Railway Children (1970)

Given that its the source material comes from a book written in 1905, The Railway Children is surprisingly modern and more than a little feminist. Its author E. Nesbit has been somewhat underestimated as a trailblazer in all sorts of ways. Among other characters in The Railway Children, she created a mother who supports her children by the power of her pen alone. Though it nominally deals with children plural, the story is really about one particular child: Roberta (Bobbie). Her safe, familiar and comparatively well-off life is upended when her father is accused of spying, and imprisoned. The family have to go and live in Yorkshire and Bobbie, while initially frightened and overwhelmed, gradually discovers her sense of agency. In particular she finds an ability to help the people she meets: from the local station master, to a Russian refugee, to a boy she might just be keen on. Though there are echos of events from the Dreyfus Affair to the rise of Russian Communism, the story stays faithful to Bobbie’s perspective and to her developing identity as a young adult.

German-American psychoanalyst Erik Erikson described the teenage years as all about the exploration of identity and who you’re going to be. The challenges are about accepting yourself and crafting a personality through which you will meet the world. It’s this identity development that’s at the heart of The Railway Children (and several other films on this list).

In the end the father, who was falsely accused, is released to join the family again. His reunion with Bobbie (“Daddy, my daddy”) is one of the single biggest tear-jerkers in the history of film*. The Railway Children is an eternal story of voyage and return. It’s not her father’s journey though. It’s Bobbie who travels, and she who is changed.

(* The Railway Children was suggested by my colleague Trish. She doesn’t have to wait for the ending to cry as even a snippet of the theme music is enough to have her welling up.)

- Heavenly Creatures (1994)

Your teens can be intense. Really intense. If any film has ever gone further down this road than Heavenly Creatures I don’t know it (and am not sure I’d actually want to see it). Based on true events, Heavenly Creatures details a story of an obsessively intimate friendship between Juliet (an early run out for Kate Winslet) and Pauline (Melanie Lynskey, less famous as she was not about to star in Titanic). It takes immersion in another person and distrust of anyone outside to extreme levels. The girls bond over a history of childhood illnesses, lose themselves in alternative realities and, when their relationship is threatened, end up killing Pauline’s mother.

Psychoanalytic analyses of the story have emphasied the shared childhood trauma the girls experienced. Also though some consider the id (Freud’s instinctual, libidinous drive of the psyche). Among other things, the id is deeply attractive and it is this aspect that Julie Burchill latched onto in a famous Sunday Times review:

“It is part of the power and glory of Peter Jackson’s unspeakably beautiful and terrifying Heavenly Creatures that he nevertheless makes a friendship that ends in carnage look like the most satisfying and enviable relationship on earth.”

- The 400 Blows (1959)

I haven’t seen The 400 Blows for pushing 40 years and I’ve never seen it as an adult. The fact that it makes this list says something about its staying power. I didn’t watch it again for this article either but instead wondered if I could think through just what had made it stick.

The story follows Antoine, a boy growing up in 1950s France. He’s what used to be referred to in my own childhood as a “tearaway”, a term often combined with either sympathy for, or blame of, the parents. He truants from school and lies that his absence was due to his mother’s death. He steals and is taken, rather heavy-handedly, to the police by his stepfather. He ends up in a youth offending centre. He is interviewed by someone (a psychologist possibly?) and the result is something so fresh and authentic that it’s the main bit I can remember.

I think the thing that thrilled me (beyond 1950s Paris being about a million times cooler than 1970s Glasgow) was, and I realise this sounds pompous, Antoine’s moral development. Theories of developing morality often stress a stage of living up to societal or parental expectations. Basically being a good boy or girl. Antoine is, exploring somewhere out beyond these boundaries. Why he does so is never entirely clear. No matter though, his sheer chutzpah is intoxicating and terrifying in equal measure. Saying his mother is dead! Is he really going to get away with it? His final escape to a beach alone seems to sum it up. He’s free! What’s he going to do? Never mind, he’s free!

- Inside Out (2015)

Recently my colleague Alex Hassett gave a talk about neuroscience research on teenagers. His conclusion, that teenage brains may struggle to control intensified emotions, might feel a little familiar to many parents.

Inside Out give us a sneak peak into how this might work. The nascent teenager is called Riley. She’s 11 and has just moved to San Francisco with her parents. Struggling to adjust to a new place and new friends, Riley is sad. In a combination of epiphenomenalism and The Beano’s Numbskulls, we see all this from the perspective of the personified emotions in the control room of her brain. The central story is the journey of Joy and Sadness round Riley’s mind to stop fundamental memories from being tainted by melancholy. Riley is controlled in the interim by Anger, Fear and Disgust. As things go wrong she’s is overwhelmed. Eventually the emotions learn to live in greater harmony. The importance of having different feelings, and even of combining them, come to the fore as Riley settles into her new life. Her made over control room is all set for the teen years. A quick tour of some other teenage brains at the end clues us in to what to expect next…

- City of God (2002)

In 2011 psychologist Steven Pinker published The Better Angels of Our Nature, arguing that violence in human societies has declined across millennia. There has been no shortage of people ready to question both Pinker’s premise and some of the reason he offers for a more pacific humanity. While he’s been criticised for excessive optimism, my own take away from Pinker’s work was different: violence certainly does seem to have declined and we are privileged to live at such a moment, however, the threads that keep barbarity in check are fragile.

City of God is the kind of film that makes you think about such fragility. Set in a favela outside of Rio de Janiero, it follows gangs and gangsters as they go through their teens and take control of the expanding drug trade. For all that it’s rightly praised as a sensual feast and an exhilarating experience, it is also seriously dark. In some of the other movies on this list there are growing-up challenges (unhappy home lives, illegal abortions, ill parents). In City of God the path to manhood is children killing other children and doing it so everyone can see how ruthless you are. Li’l Zé the lead gangster rises to power not only because he is the cleverest but also because he is the one who is prepared to go furthest in his disregard for human life.

You can link in the development of City of God’s characters with theories of moral development and end up in a far scarier place than The 400 Blows. In many ways favela teenagers’ growth is quite conventional but takes place a situation where valued outcomes and a sense of justice are divorced from a wider social group. The City of God is what emerges when whole societies are disregarded. As in Lord of the Flies, people brutally remake the rules from the ground up. It’s not always an easy watch, but is really is a great film.

- Ferris Buller’s Day Off

A quick trawl of the internet will tell you that this film has attracted as much affection and fan analysis as any film of the 80s (like the Guardian’s Hadley Freeman I think the 80s an unjustly derided cinematic decade). What’s it about? On the surface not that much. Ferris takes a day off school by pretending to be sick. He heads out with his depressed friend Cameron in Cameron’s dad’s vintage Ferrari. Ferris gets his girlfriend Slone out of school by pretending to be her father and the three enjoy a perfect day in Chicago.

What’s it really about? Theories are legion: from social class to Cameron’s lousy home life. There is even one about Ferris being a aspect of Cameron’s dissociated state of mind (in a sort of Fight Club way). Actually many of these analyses are pretty good and there is certainly a lot to be said about social status and wealth in all the films of Ferris-director John Hughes. For an apparently superficial film there’s a lot in. Ferris, like Antoine in The 400 Blows, actually engages in some objectionable and selfish behaviour. He lies outrageously and gets his best friend into serious trouble. But, also like Antoine, we find him utterly charming (partly down to Matthew Broderick’s performance). Unlike Antoine though, everyone else finds Ferris charming too. Except his meanie high school principal, who is horribly punished for his poor judgement.

In the end Ferris is a offbeat kid’s fantasy of what might happen if everyone liked you despite being you being odd and different. Instead of juvenile detention Ferris gets to serenade a cheering carnival parade with a rendition of Twist and Shout.

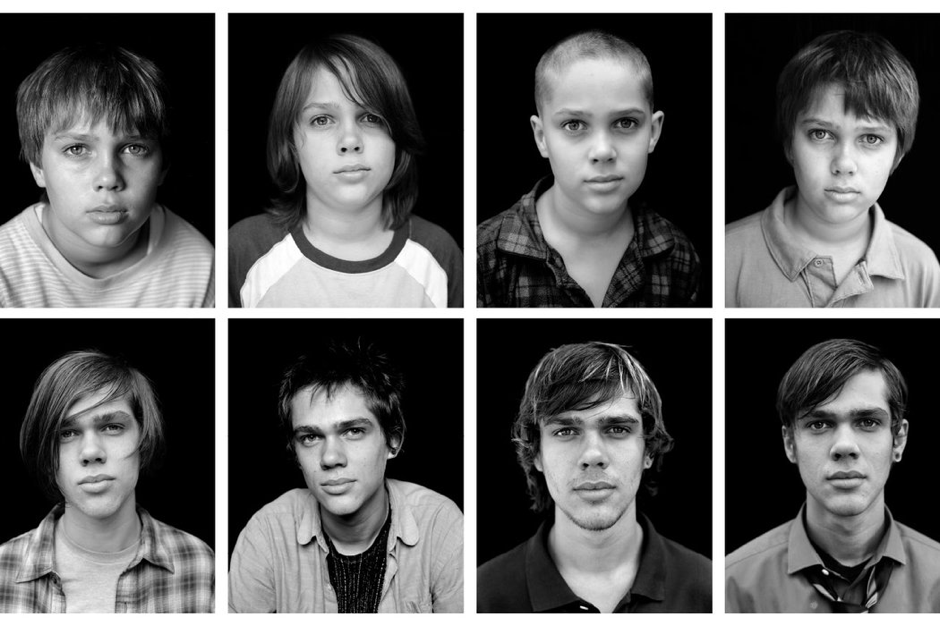

- Boyhood

Not a lot happens in Boyhood. And yet everything happens. The story is absolutely unconventional in that there isn’t really one.

Boyhood paints a picture of something far more like regular life than most films. However, it has the added, and unique, device of filming with the same cast for a few weeks annually for 11 years. It follows the growing up of six-year-old Mason, a child of divorced parents living in Texas. And he… well he grows up. And he leaves home. And his mum reckons with what her life has and hasn’t been. It’s both very Eriksonian and as fresh and authentic as the therapist scene in The 400 Blows. As Slate.com’s Dana Stevens says in her review, Boyhood is “as transcendent as it is ordinary – just like life”.

- To Kill a Mockingbird

The psychoanalyst Melanie Klein offered a view of growing up where the ability to perceive complexity, especially moral complexity is central. From an early infantile world where the world is composed of simple binaries (so called “good” and “bad” objects) we move to a deeper appreciation of complexity. Rather than simply good and bad, people become more complex actors holding ambiguities and contradictions. Klein considered that at least a move towards a greater appreciation of complexity is essential to healthy emotional development.

For me, the primary pull of To Kill a Mockingbird is how we learn about such complexity through the eyes of two children. The two, Jean Louise “Scout” Finch and her brother Jem grow up in small-town Alabama in the 1930s. They find out about human weakness and ambiguity in multiple ways though primarily through the racism of the townspeople. This is brought into sharp focus when their father, Atticus, is appointed to defend a black man, Tom Robinson, falsely accused of raping a white woman. Scout witnesses not only a lynch mob but also a heartbreaking miscarriage of justice.

As well as the greater clarity with which the children view their neighbours (including the recluse, and sometime bogeyman, “Boo” Radley) they also begin to see their father as having a life beyond them. They don’t exactly learn to see him as complex (Atticus Finch is perhaps one of the most unambiguously heroic characters in the history of fiction**) but as someone who has other relationships, other allegiances and, at the very end, a certain flexibility about how the moral principles are applied. Perhaps the central moment for Scout is when black townspeople stand as Atticus leaves the court after Tom’s guilty verdict. The line “Miss Jean Louise, stand up. Your father’s passing” will probably finish off any tissues you have left after The Railway Children.

(** I’m just concentrating on TKAMB here. Atticus emerges in a somewhat different light in author Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchman.)

- A Monster Calls

Conor’s mother is dying of cancer. He can’t do anything about it and is tormented by a terrifying dream where she falls away from him. He’s bullied at school, his father lives abroad and he’s being sent to live with his Grandmother (whom he can’t stand). In the midst of this he starts receiving nocturnal visits from a terrifying monster who tells him stories with echos of his own life…

Adapted by Patrick Ness from his own novel, A Monster Calls explores how we stop ourselves feeling things that we can’t bear, and how we need to feel them anyway. I’ve never found a piece of fiction that has offered a better account of the psychoanalytic idea of defense mechanisms. Though it was only classed a 12A in the UK and a PG-13 in the US, don’t go in unprepared. This is as raw a couple of hours in the cinema as you’re going to get. See it nonetheless. It really is quite something.

- Dirty Dancing (1987)

In some ways Baby (Dirty Dancing’s lead character played by Jennifer Grey) is like a 1960s version of The Railway Children’s Bobbie (minus the bonnet and petticoats), or 2007’s Juno, (though without being pregnant). In all three cases girls become young women, their choices and desires are validated and their identity crystalises. Again it’s a fairly simple story. Boy meets girl. Actually girl meets boy. As you’ll see the distinction is important. Baby, goes to a Catskill Mountain holiday resort with her well-to-do family. Here she meets and falls for Johnny, the wrong-side-of-the-tracks dance instructor (the late Patrick Swayze’s finest hour). Why does Dirty Dancing take my palm though? Two reasons:

Firstly it has to be one of the most feminist films ever made. While it’s frequently dismissed as teen schlock or high camp, it’s so much more. I’m drawing heavily on Hadley Freeman’s analysis here, but how many teen movies address the horrors of illegal abortion in the 60s? How many are completely centred around the viewpoint of a young female protagonist? And feature a young woman gets to feel (and act on) desire without being punished? The film’s writer Eleanor Bergstein wanted to address all these themes but in a way that wouldn’t alienate the audience.

The second reason for Dirty Dancing’s primacy, and the one that swings it for me, goes back to Erik Erikson. Erikson termed the stage of identity development in your teens and 20s “fidelity”, and if there is one thing I’m a sucker for, it’s a story with fidelity and truth at its heart. Even more than a dance training montage, and that is usually enough to sell me on a film all by itself. Towards the end of Dirty Dancing Johnny is wrongly accused of a crime and Baby risks everything to save him. She has realised something important about the difference between her own privileged life and the far more parlous existence of people like Johnny. This isn’t a diving into a river/jumping off a building kind of rescue, but something far more real and identifiable. She risks the love of her father and her reputation (no small consideration in 1963) by saying she was with Johnny all night. Baby’s actions are genuinely heroic and are not just motivated by the desire for a close rhumba and more, though I repeat she does very much want this and the film does not judge her for it. Ultimately she is absolutely true to herself and to what she knows is right. When Johnny comes back in the final scene and announces “Nobody puts Baby in the corner!” I think this is the reason why the audience roars her on to the time of her life. If you find you aren’t out of your seat cheering, maybe you should watch it again.

So that’s my list. Near misses include Juno, Pretty in Pink, and Up (because growing up isn’t only for the young). What did I miss? Let me know in the comments below or on Twitter @drjohnmcgowan.

Discursive of Tunbridge Wells

Discursive of Tunbridge Wells John McGowan

John McGowan 14716

14716