Technological advances mean virtual reality has gone from a clunky gimmick to the next stage of human-computer interaction and social engagement. Whole worlds can be explored without leaving the room and people can experience others’ perspectives at the flick of a virtual switch. Richard Weatherall, Senior Psychology Technician at CCCU explores current research in the realm of VR.

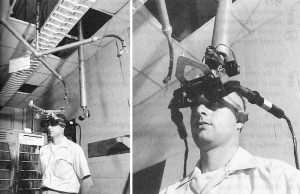

Virtual reality is not a new concept. While the specific origins of the term are debated, advances in photographic technology allowed the simple stereoscopic device, the ‘View-Master’, to appear in the 1940s, allowing people to view tourist attractions and travel locations in primitive, yet revolutionary 3D. In the 1960s, large mechanical devices offering stereoscopic imaging and binaural sound, such as the Sensorama and Sword of Damocles (named after its formidable, ceiling-suspended appearance) began emerging, although were hindered by the graphic technology of the time. Virtual reality research continued in fits and starts through the next few decades, mainly focusing on medical and military applications before being adopted by the games industry. Poor graphics, user health concerns and expensive production contributed to commercial failures and lack of general interest from brands like Sega (Sega VR, 1991), Apple (QuickTime VR, 1994) and Nintendo (Virtual Boy, 1995).

Skip ahead 20 years and VR is back with a vengeance. Technology developments not only allow devices to display thousands of pixels per eye display but also combine motion tracking and 3D audio for incredibly immersive experiences. Development of VR technology has grown almost exponentially in the last few years. Social media and networking company Facebook branched into VR through its acquisition of Kickstarter company Oculus VR in 2014 for 2 billion USD, and now has around 400 employees dedicated to VR development. Google, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Sony and Samsung all have dedicated Virtual and Augmented Reality sections.

While current generation VR is still developing, its applications in research are already far reaching. Detailed and realistic environments allow for high levels of ecological validity while allowing research almost full control of the environment and testing situation, as well as enabling the standardisation of social variables. Studies have shown performance in VR to correlate with equivalent pen and paper measures whilst at the same time more accurately reflecting everyday behavior. It has also been shown to be more immersive than studies using visual images as it stimulates multiple sense modalities. The engaging nature of VR has also been shown to increase motivation as well as participant focus.

The immersive nature of VR enables existing paradigms to be taken to another level, allowing, for example, embodiment studies to ‘literally’ put the their participants in another persons’ skin. Research has shown the reduction of negative stereotypes in areas such as race, age and body image (height and weight); as well as allowing new insights into the study of pro-social behavior, bystander effect and studies on bullying. This immersion has also lent to management of addictive behaviors such as gambling and nicotine dependency, in addition to management of various phobias, such as spiders, heights, flying and claustrophobia, as well as social anxiety and public speaking. The ability to be instantly transported to a forest or mountain top has profound implications for those with physical disability.

The virtual nature of these environments also open new possibilities for lab based experiments. Cognitive tests requiring specific room layouts can be recreated regardless of physical location. A participant can walk through room after room, each as exact or varied as required with little more than a few lines of code.

While lower functionality, cheaper smartphone based systems are available, the graphical computing power required to run a current generation VR setup still makes them fairly inaccessible to the general population. However, popular games companies Sony and Microsoft both plan to release VR devices with their accessible games consoles, bringing VR into the mainstream. Online shopping, whose paradigm drastically changed when people began purchasing items without the physical need to enter a store, is now merging old and new paradigms to create virtual stores of any design that can be imagined. Art programs allow freehand drawing in 3D space. News companies can show experiences that put you directly into a war zone or refugee camp. Social events and entertainment can allow people to connect in ways only seen in science fiction. The pornography industry, historically dictating the medium of new media technology has seen an increase of 250% in VR content in the last year alone. As universities adopt more remote learning to encourage engagement, how long before all lectures are attended virtually?

While we may still be some way away from the dystopian view of unmoving amorphous human blobs only and totally connected to the world through technology, it seems apparent that before long, every possible human experience, will be possible through VR. Until then however, we should seize the profound opportunity afforded, embrace the fantastical opportunity available, and bring research to the cutting edge of technology and human experience.

References for studies discussed in this article are available on request from psytech@canterbury.ac.uk

psychology

psychology Marcus Roberts

Marcus Roberts 1897

1897

VR is a interesting subject and something I would like to include in my art practice. I find the whole concept very exciting, and look forward to seeing future applications of VR. The technically is expanding rapidly – only last year my lecturer suggested I look into VR for my research project but I thought it would be too expensive and complicated. I was surprised how cheap some VR headsets are, and how easy it is to download apps/games to use. I am particularly interested in seeing how these virtual spaces can be places of learning and creativity.

Thank you for the post.