Suzanne Bartholomew, PhD student in Developmental Psychology shares her view of the Technology and Media in Children’s Development Conference – organised by the Society for Research in Child Development, California, USA.

Technology and Media in Children’s Development

October 27-30,2016, Irvine, California

So here I am at my desk, fresh (fighting jet-lag but feeling like a kid at Christmas) and back from Irvine, California no less. I had been attending a four-day special topic meeting organised by The Society for Research in Child Development (SRCD). Since 1933, this US based society has encouraged multi-disciplinary research on child development and supported the application of such findings in order to benefit both children and families (Hagan, 2000). In the introductory speech, the conference was declared as the SRCD’s first special meeting “SELL OUT” with 100% attendance capacity booked by organiser Stephanie Reich. Not surprising to me as the meeting was titled: ‘Technology and media in children’s development’. Could there be a more relevant topic for conference discussions? (Maybe I carry a slight bias for the topic as a huge section of my research concerns child and parent use of media.)

The timeliness of this conference could not have been more perfect, as The American Academy of Paediatrics (AAP) has recently adapted their recommendations to meet the changing face of media use by younger consumers. Historically, the AAP have stressed the negative aspects of screen time, relying on empirical evidence implying possible interruptions to a child’s typical developmental trajectories. AAP previous recommendations included that parents of children under the age of two years should apply a blanket ban use of all media devices. As we know today, this seems pretty much an impossible guideline for any parent.

With electronic device use, most commonly now the mobile kind, being an integral part of peoples’ lives, it is not any surprise that the UK government (2014) suggests that 87% of UK adults (44.6million) use the internet, up 3.5million since the report in 2011 www.ons.gov.uk. Advances in touch screen technology has enabled younger children to become consumers of this digital world. The newest AAP guidelines acknowledged these changes, scrapping their blanket ban and replacing it with no mention of time limits but instead recommending that online media use for up-to-five year olds should be as much supervised by the parents as the childs’ non-media time (Radesky, Schumacher, & Zuckerman, 2015). Read more details of these changes on the AAP website:

https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/pages/media-and-children.aspx

My mission (if I chose to take it, which I so obviously did; in their right mind, who wouldn’t?) was to fly out to California and carry out a two-hour poster presentation titled ‘Digital effects of touch screen technology on focused attention and executive function’ (EF). The poster incorporated two studies. Primarily, research carried out by Dr Amanda Carr in the Canterbury Christ Church observation labs. The study examined attention in a sample of 18 children aged 10-36 months. Attention levels were recorded before and after both free play and touchscreen tablet play. Results concluded that although there was an overall drop in attention in both conditions, there was no significant difference in attention after tablet play or free play. This suggests that playing on a touchscreen tablet may not have such a negative association with attention span as commonly reported.

The second project was my own work. I looked at the association of screen time with EF and classroom behaviour in an older sample of 8-10 years (N = 276). Correlations hinted at a marginal negative association between screen time and EF skills. However, a larger positive effect was found between screen time and classroom behaviour. We concluded for our samples that, with very young children, screen time had no immediate negative effect on focused attention but, as age and screen time increased, so the effect on EF and classroom behaviour become more pronounced. Both studies have follow up research being carried out as you read.

Presenting both studies to an audience of highly knowledgeable and respected academics was an intimidating prospect that I tried to think about logically rather than emotionally. I was unsure which of the two projects I was more scared about explaining; under pressure to explain Dr Carr’s research 100% correctly, I couldn’t get anything wrong! Or my own, which, surrounded by all these highly educated people, I felt was possibly all wrong anyway. But that was to take place on the Saturday evening, and I had two days of conference before then.

I spent those two days sprinting from one set of talks to another. My conference diary of ‘things to see’ was full from 8.30am until 8pm. The conference offered many different types of talks including keynote speeches, hour long lectures, symposia (a ninety-minute session with three or four researchers giving twenty minute talks followed by Q and A and flash talks), an hour long session with five or six talks in rapid succession with limited Q and A—all offering and delivering valuable insights into contemporary media use research. There was much information I could share here but for space limitations I shall concentrate on reporting on keynote speeches.

Opening the conference proceedings were the principle keynote speakers, renowned psychologists Kathy Hirsh-Pasek and Roberta Michnick Golinkoff with their lecture “Putting the ‘Education’ back in Educational Apps” (Hirsh-Pasek, Zosh, Golinkoff, Gray, Robb, & Kaufman, 2015). The room was full to bursting point as the issues of the development and construction of apps designed for the young consumers were brought up. The conference audience was held captivate (me included) as it was explained how so many apps are being marketed as not just entertaining but also educational.

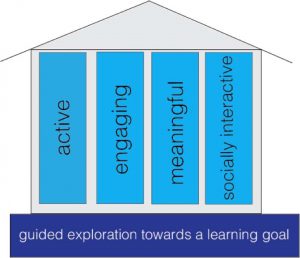

The psychologists explained that such claims are being made without much consideration of the known psychological processes of child learning and development. They offered us the four pillars of learning: a comprehensive framework designed to enable apps designers and app buying parents alike, the ability to deliberate on the apps associated learning outcomes.

(Hirsh-Pasek, Zosh, Golinkoff, Gray, Robb, & Kaufman, 2015).

Summing up the vast amount of information that was given, the four pillars represented the factors required for learning to take place: active, engaging, meaningful and socially interactive. The added necessity was that all four pillars are embedded with the context of guided exploration towards a learning goal. This framework can be applied to almost any contextual learning situation. However, as a critical element of the digital world, the researchers gave examples of supporting evidence. An example for the social interaction pillar was the teaching of a child via three different social conditions; live video chat between a teacher and the child, the child watching a recording of another child having a live video chat with the teacher and lastly the child watching a pre-recorded lesson from the teacher. Hirsh-Pasek and Golinkoff reported their finding with equal significant learning gain from condition one and two whilst no significant gains made in learning for condition three. The other three pillars were highlighted by research examples and much to the audiences delight the lecture was interspersed with amusing clips of educational apps and not so educational apps.

A full PDF of this lecture can be found at :

Doing a bit of name dropping now, further to the fantastic Hirsh-Pasek and Golinkoff session the conference itinerary of keynotes included:

- Justine Cassell: Addressing the influence of peers and how this intrinsically dyadic interpersonal closeness could be replicated by a child with a virtual friend.

- Patricia Marks Greenfield: Appling the theory of social change in a world where digital technology is a key aspect of our culture.

- Ellen Wartella: Addressing public policies and asking how the media can be responsible for childhood issues such as obesity.

I enjoyed all of the above sessions, but as an admirer (dare I say fan?) I was most looking forward to attending the Sonia Livingstone keynote speech. Professor Livingstone was introduced as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire after having been awarded the OBE in 2014 ‘for services to children and child internet safety’. The audience delighted in this description with energetic claps and cheers erupting around the room. In her talk, she asked the question, “What did I learn from spending over a year following around – at home and school, offline and online – a class of 13 year olds from an ordinary urban London school?” Sound interesting? Yes, it was. Professor Livingstone explained her ethnographic study in great detail, describing how this journey challenged popular inferences about teenagers’ use of the media, outlining the conception of the ‘digital native’. Further, she questioned the assumption of a teenager’s need to be constantly connected to the digital world, suggesting, instead, that a teenager’s need to be able to enter the digital world when they wish to grants them agency. As a parent to three teenagers, this explanation has made me start to rethink my worries about their mobile phones becoming an extension of their hands. I am taking on board their possible need to protect their digital life in doing so protecting their individuality.

The accompanying book ‘A Class: Living and Learning in the Digital Age’ (Livingstone, & Sefton-Green, 2016) is top of my Christmas list, I will ask my children to gift it to me!

(Details of work by Professor Livingstone can be found on the LSE website.

http://www.lse.ac.uk/media%40lse/WhosWho/AcademicStaff/SoniaLivingstone.aspx

And so to the reason I was in the United States: the moment had arrived for this highly stressed but excited researcher to present this ‘well-travelled’ poster (approximately 5,318 miles from London to California). We were on stand number ten; number ten out of forty five! That’s a lot of poster presentations for fellow academics to get through. I nervously stood before our poster wondering if after sitting through ten hours of talks earlier in the day that this would just be too much to ask of my fellow attendees? Maybe this would be one poster session too many?

(Please ignore the distortion of the picture. The poster board was bent!)

Nope! It seemed not. The room was teeming; to my relief, enthusiasm had not waned. Explaining the research and answering questions to many interested researchers made the session a great success. I had completed the mission, I felt extremely proud of our research, a feeling akin to attending the Christmas nativity play when your child has a ‘talking’ role.

And so here I am sitting at my desk still suffering with jet lag but still feeling like a kid at Christmas and planning to put myself through the conference experience again as soon as possible.

Hagen, J. W. (2000). Society for Research in Child Development. AE Kazdin, Encyclopedia of Psychology, 7.

Hirsh-Pasek, K., Zosh, J. M., Golinkoff, R. M., Gray, J. H., Robb, M. B., & Kaufman, J. (2015). Putting education in “educational” apps lessons from the science of learning. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 16(1), 3-34.

Livingstone, S., & Sefton-Green, J. (2016). The class: Living and learning in the digital age. NYUPress.

Radesky, J. S., Schumacher, J., & Zuckerman, B. (2015). Mobile and interactive media use by young children: the good, the bad, and the unknown. Pediatrics, 135(1), 1-3.

psychology

psychology Marcus Roberts

Marcus Roberts 1323

1323