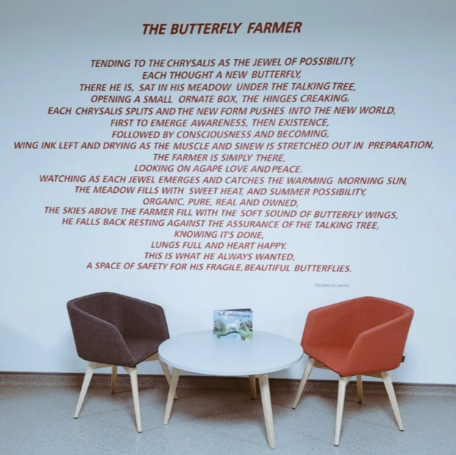

By Tom Delahunt, the #hobopoet

In contemporary nursing education, the intersection of art, activism, and social justice remains a vital yet often overlooked dimension of vocational training. As Audre Lorde (1984) powerfully stated, “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,” underscoring the urgency for alternative pedagogical approaches that challenge structural inequities within higher education institutions (HEIs). Integrating art as a form of activism in nursing education aligns with critical pedagogy principles, fostering self-reflection, resilience, and a deeper understanding of the social justice challenges within healthcare.

Eli Clare (1999) in Exile and Pride emphasizes how storytelling and creative expression serve as tools for confronting systemic ableism and oppression. Embedding the arts into nursing curricula not only amplifies marginalized voices but also provides students with the opportunity to engage critically with the embodied nature of care and the complexities of healthcare inequities. Kimberlé Crenshaw’s (1989) concept of intersectionality offers an essential framework for understanding how race, gender, and class intersect within nursing. As nursing students navigate these socio-political landscapes, integrating poetry, visual arts, and narrative medicine into their education fosters cultural competence and amplifies the often-silenced lived experiences of both healthcare professionals and patients. In this way, the arts move beyond supplementation; they become a radical reimagining of what it means to be a nurse in the 21st century.

This reimagining is urgent. Recent parliamentary discussions in the UK highlight the need to protect the nurse title against dilution, ensuring that only those with accredited education and registration can claim it (Royal College of Nursing, 2025; Nursing Times, 2025). Future-proofing nursing education demands curricula that not only meet regulatory standards but also prepare nurses to engage in social advocacy. Arts-integrated education serves as a powerful tool for fostering advocacy and equipping nurses to confront systemic inequalities within healthcare.

The integration of creative methodologies serves a dual purpose: nurturing critical consciousness (Freire, 1970) and empowering nurses to challenge the socio-political dimensions of their profession. As HEIs consider reforms to pre-registration nurse training, artistic activism must be embraced not as an auxiliary practice but as an essential element of a socially just, future-oriented nursing curriculum. By embedding arts-based practices into education, institutions can cultivate nurses who are not only clinically competent but also capable of driving meaningful, transformative change within the healthcare system.

Nursing has long been situated at the intersection of care and activism. In an era where the NHS faces increasing strain, nursing applications are plummeting (BBC News, 2024), and working conditions are deteriorating, the role of the nurse extends far beyond bedside care. It is a profession rooted in radical resilience, where creativity and care become acts of protest against the system.

The decline in nursing applications—down by 20% since the pandemic (UCAS, 2024)—reflects both economic and institutional failures, as well as a growing disillusionment with the profession. The high cost of training, low wages, and relentless working conditions have made nursing less attractive, despite its essential nature (The Guardian, 2024). As Lorde (1984) reminds us, “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” The current exodus from nursing is itself an act of resistance, rejecting a system that undervalues caregivers.

Creativity as Resistance: The Role of Art in Nursing

Nurses have long used creative methods to process trauma, build community, and advocate for change. Projects like the Poetic Nursing Heart exemplify how creativity fosters resilience, while artworks such as Banksy’s Game Changer (2020)—which depicts a child discarding superhero toys in favour of a nurse—illustrate the cultural recognition of nursing as radical and essential.

Crenshaw’s (1989) theory of intersectionality reveals how race, class, and gender shape nurses’ lived experiences. Nurses from marginalized communities, particularly Black and working-class nurses, face disproportionate burnout and systemic inequities (RCN, 2023). Creative expression becomes a form of healing, as bell hooks (1994) asserts, “the function of art is to do more than tell it like it is—it’s to imagine what is possible.”

The Future: Reimagining Nursing Through Art and Activism

If nursing is to survive as a profession rooted in care and resistance, it must embrace radical change—advocating for fair wages, fostering creativity within education, and recognizing the arts as an integral aspect of healing. Integrating art into nursing education offers more than personal resilience; it is a form of political engagement that reaffirms the role of nurses in acting to resist oppressive systems.

As the nursing profession faces a deepening recruitment crisis, with applications falling by 15,000 since 2021 (Lillywhite, 2024), the NHS’s financial struggles and workload pressures have made nursing an increasingly unattractive career choice. Yet, the solution to this crisis lies not only in financial incentives but in reigniting prospective students’ connection to the profound purpose of nursing. Creative therapeutics, integrating artistic approaches into healthcare education, can promote resilience and well-being among nurses, making the profession more appealing to newcomers (Malchiodi, 2012; Love, 2014).

However, without evolving recruitment efforts to incorporate alternative strategies, the profession will face a future marked by declining numbers and worsening patient care. The NHS, already undermined by underfunding and privatization (Hunter, 2023), risks further degradation without meaningful intervention.

The systematic underfunding of the NHS is not merely the result of poor policy decisions but some might say a deliberate effort to undermine publicly funded healthcare, driven by the interests of private companies. Since 2012, private companies with ties to Conservative politicians have secured NHS contracts worth billions, further eroding public healthcare (The Guardian, 2014). This process, framed as a “manufactured crisis,” is used to justify the privatisation of public services, creating a two-tier healthcare system where those who can afford private care receive preferential treatment, while the most vulnerable remain in an overstretched, under-resourced public sector (Fisher et al., 2022). These policies are not accidental; they align with a neoliberal agenda that seeks to replace universal healthcare with profit-driven models, deepening inequality within the system (Lethbridge, 2023).

Healthcare and nursing are far more than the mere delivery of services; they are about compassion, human connection, and addressing the holistic needs of individuals. Nurses are at the forefront of this dynamic, offering not just clinical care but emotional support, advocacy, and a sense of dignity to those they serve. The continued underfunding and privatization of the NHS threaten the very core of this mission, undermining the ability of healthcare professionals to provide the compassionate, patient-centred care that is essential to the well-being of society. To truly honour the values of nursing and healthcare, we must prioritise a system that values people over profit, ensuring that all individuals, regardless of their financial means, have access to the care they need.

References

Banksy [2020]. Game Changer. Retrieved from https://www.banksy.co.uk [Accessed: 14 March 2025].

BBC News [2024]. Nursing crisis: Why nurses are leaving the NHS. BBC News, 3 March. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-56495712

[Accessed: 14 March 2025].

Clare, E. [1999]. Exile and Pride: Disability, Queerness, and Liberation. Duke University Press.

Crenshaw, K. [1989]. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex. University of Chicago Legal Forum. Available at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8

[Accessed: 14 March 2025].

Fisher, M., Green, D., & Wilton, L. [2022]. Healthcare Privatisation and Inequality: The Changing Face of Public Services. London: Policy Press.

Freire, P. [1970]. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Continuum.

Hooks, b. [1994]. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. Routledge.

Hunter, D. [2023]. Manufactured crisis: The politics of NHS underfunding and its consequences, British Journal of Health Policy, 45[2], pp. 187–201.

Lethbridge, J. [2023]. The Neoliberal Erosion of Public Healthcare: Policy, Power, and Profit. Bristol: University of Bristol Press.

Lillywhite, M. [2024]. Nursing course applications in the UK fall for the fourth year, BBC News Gloucestershire, 13 March. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cdrx6l45le0o [Accessed: 14 March 2025].

Lorde, A. [1984]. Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Crossing Press.

Love, G. [2014]. Healing Arts: The Therapeutic Potential of Art, Drama, and Music. London: Routledge.

Malchiodi, C. [2012]. The Art Therapy Sourcebook. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

Nursing Times [2025]. Nurses’ Professional Identity and the Protection of the Title. Available at: https://www.nursingtimes.net [Accessed: 14 March 2025].

Royal College of Nursing [RCN] [2023]. The impact of systemic inequities on nurses of color. Retrieved from https://www.rcn.org.uk [Accessed: 14 March 2025].

The Guardian [2014]. Private companies with links to Conservatives win NHS contracts, The Guardian, 17 November. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/nov/17/private-companies-conservatives-nhs-contracts [Accessed: 14 March 2025].

UCAS [2024]. Annual admissions report. Retrieved from NHS grows its nursing workforce with UCAS’ unique student insight | Business, Apprenticeships | UCAS [Accessed: 14 March 2025].

The Poetic Nursing Heart

The Poetic Nursing Heart Jack Charter

Jack Charter 1941

1941