by Tom Delahunt the #hobopoet, and Dr Dave Boyd

Tom: In the realms of physical combat and artistic expression, there exists a curious intersection where the worlds of boxing, British wrestling, and poetry converge. While seemingly disparate pursuits, each holds a rich tapestry of symbolism, embodying themes of struggle, resilience, and the human condition. This exploration delves into the parallels and symbiotic relationship between these disciplines, highlighting the shared motifs that resonate through the ages.

Boxing, often dubbed the “sweet science,” encapsulates the primal essence of combat sports. Its origins trace back to ancient civilizations, where pugilistic contests were revered as tests of strength and skill. Throughout history, boxing has transcended mere physical confrontation, evolving into a metaphor for the human journey. In the ring, fighters confront their inner demons and external adversaries, engaging in a dance of controlled aggression and tactical prowess.

British wrestling, with its roots entrenched in carnival entertainment and sporting spectacle, offers a distinct contrast to the raw intensity of boxing. Yet, beneath the flamboyant theatrics lies a narrative of struggle and triumph. Wrestlers, adorned in colourful personas, grapple with larger-than-life personas, embodying archetypal heroics and villainy. Dr Dave Boyd’s exploration of British professional wrestling unveils its nuanced cultural history, revealing how it mirrors societal norms and values.

——————————————————————————————————————–

Dave: When I was first approached to contribute to this blog by comparing poetry to wrestling, I must admit, I was perplexed. The idea seemed unconventional, even bizarre. What could the refined, evocative world of poetry possibly have in common with the theatrical, physical spectacle of professional wrestling? However, as I delved deeper into the symbolic qualities of both, it became clear that these two seemingly disparate realms share more than one might initially think. Both poetry and wrestling are rich in metaphor, drama, and performance, each offering unique insights into the human condition. This conversation also connects to semi-recent scholarly discussions centred around finding new uses for various artforms in research to better understand the world and the people around us. Hoult et al. advocate for the use of poetry as a methodological tool, arguing that its emotive and expressive qualities can uncover layers of meaning often missed by traditional research methods. Similarly, in the paper ‘Scholarly grappling: Collaborative ‘work’ in the study of professional wrestling’, Litherland et al. highlight professional wrestling as a valuable subject for scholarly inquiry, emphasising how its performative nature can illuminate cultural and social dynamics. Both works underscore the importance of interdisciplinary approaches, demonstrating that poetry and wrestling, despite their differences, can provide rich, nuanced insights into the complexities of human behaviour and societal structures. Therefore, the discussion of comparing the symbolic power of poetry to that of meaning being generated through the physical, visual spectacle of professional wrestling is a particularly poignant one.

Barthes once defined wrestling as “ideal intelligence of things, a euphoria of humanity, raised for a while out of the constitutive ambiguity of everyday situations and installed in a panoramic vision of a univocal Nature”, suggesting that professional wrestling takes people out of their ordinary experiences and puts them in a world where everything seems clear and straightforward. It’s like being lifted into a world where everything makes perfect sense, unlike the complexities and uncertainties of everyday life. There is a contradiction here when relating to comparing wrestling to poetry. While professional wrestling simplifies and clarifies things according to Barthes, poetry often embraces the ambiguity and complexity of life. It can delve into the nuances of human experience, exploring emotions, thoughts, and perspectives in a way that doesn’t always provide clear-cut answers. Poetry might evoke multiple interpretations and emotions simultaneously, reflecting the intricate nature of existence. So, while wrestling aims to provide a clear narrative, poetry thrives in ambiguity and contradiction, offering a different kind of understanding and engagement with the world.

However, despite the apparent differences, there still stands a strong contrast between both forms. Just as wrestling allows temporary escapism from the complexities of life, poetry can also offer a form of respite or elevation from mundane reality. Through its use of language, imagery, and symbolism, poetry can transport readers to a heightened state of awareness or understanding, much like the “panoramic vision” described by Barthes. Additionally, while wrestling presents a simplified version of reality, poetry often distils profound truths or insights into succinct and evocative language, offering moments of clarity and revelation amidst the ambiguity of human experience. Thus, both wrestling and poetry can serve as vehicles for transcending everyday life and accessing deeper levels of meaning and emotion.

——————————————————————————————————————–

T: Poetry, the art of distilled emotion and linguistic mastery, serves as a vehicle for introspection and expression. From epic ballads to poignant sonnets, poets harness words to capture the essence of human experience. Many poets throughout history have also been fighters in their own right, engaging in metaphorical battles with language and societal conventions. Their verses echo the rhythm and cadence of combat, invoking imagery that resonates on a visceral level.

At the heart of these disciplines lies a common thread: symbolism. Whether it be the pugilist’s struggle for redemption, the wrestler’s portrayal of heroism, or the poet’s quest for truth, each endeavour is imbued with layers of meaning waiting to be unravelled.

In the world of boxing, symbolism permeates every aspect of the sport, from the rituals of the ring to the narratives woven around its champions. The boxing ring itself becomes a battleground where warriors confront their fears and aspirations. The ropes, symbolic of boundaries and constraints, confine fighters within the arena of combat, while the bell tolls the passage of time and the inevitability of fate. Even the gloves worn by boxers carry significance, serving as both weapons and shields in the pursuit of glory.

British wrestling, with its theatrical flair and larger-than-life characters, offers a canvas for storytelling akin to epic poetry. Wrestlers adopt personas that embody virtues and vices, playing out morality tales in the squared circle. From the valiant hero fighting against insurmountable odds to the dastardly villain plotting nefarious schemes, each wrestler becomes a symbol of broader societal themes. Dr Boyd’s research sheds light on the cultural significance of these personas, revealing how they reflect the hopes, fears, and aspirations of the audience.

——————————————————————————————————————–

D: A prime example of such symbolism being portrayed through wrestling characters is from the famous ‘Attitude Era’ of late 1990s to early 00s WWE, whereby the industry saw a boom in popularity arguably due to the audience living vicariously through the anti-establishment, rebellious actions of Stone Cold Steve Austin – a rebellious icon in wrestling, standing up against authority and embodying toughness and resilience. His defiance of the establishment and refusal to conform resonated with fans who admired his independent spirit. Austin’s character symbolised individualism and freedom, inspiring audiences to embrace their own strength and stand up for what they believe in. With his signature gestures and catchphrases, he became a pop culture icon, representing empowerment and defiance against the odds.

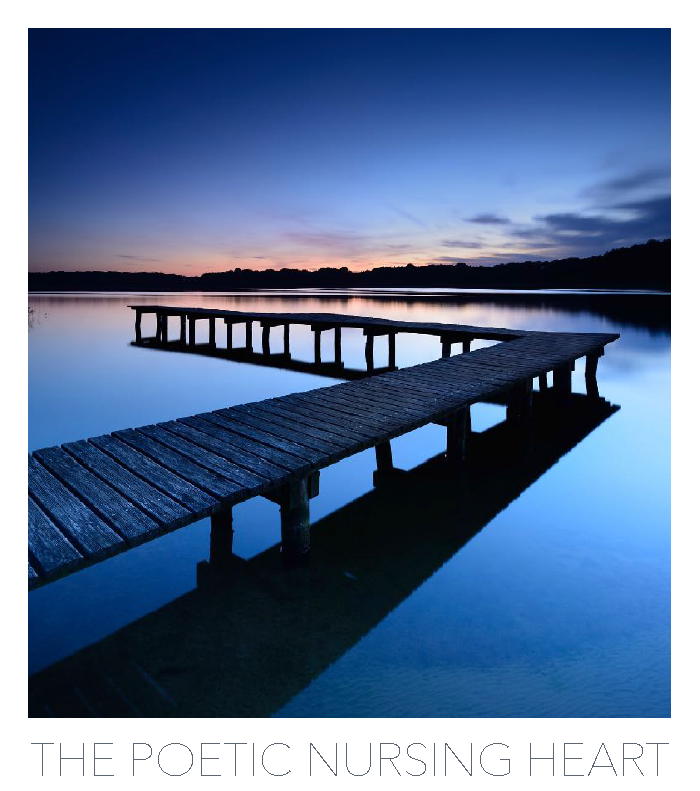

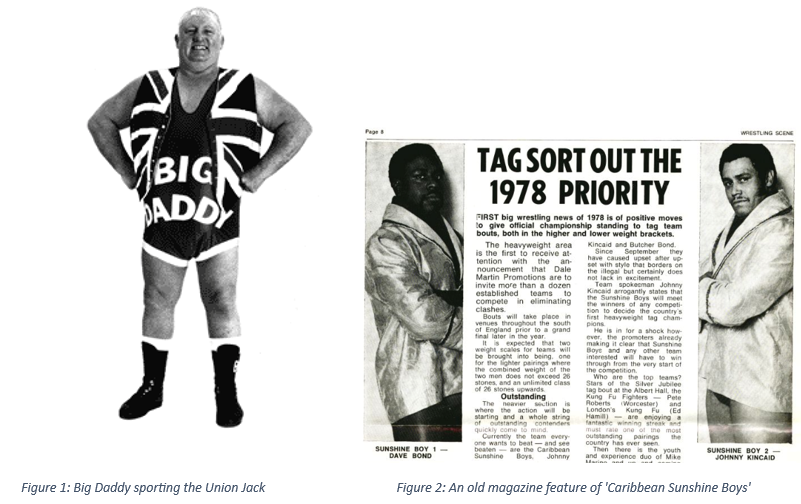

In British wrestling history, Big Daddy, a beloved figure in British wrestling, stood as a symbol of national pride and heroism during the 1970s and 1980s. With his iconic Union Jack attire, he embodied the spirit of working-class Britain, captivating audiences with his larger-than-life presence. Big Daddy’s persona resonated with fans as a champion of the common man, engaging in theatrical battles against villainous opponents that reflected everyday struggles. His family-friendly appeal and entertaining matches made him a beloved figure for audiences of all ages, fostering a sense of unity and community. Of course, an alternate reading of this era can relate to the notion of toxic nationalism in the context of racial tension within the period. Less favourable representations of race and nationality were observed, such as the ‘Caribbean Sunshine Boys’ – a team comprised of wrestlers Johnny Kincaid and Dave Bond, performing as wrestlers from Barbados despite both performers being native Londoners. As the documentary ‘When Wrestling Was Golden: Grapples, Grunts, and Grannies’ (Originally aired on BBC Four), this racially stereotypical characterisation of Blackness served as a symbol of both hope and fear amidst the racial tensions of 1970s Britain. Facing discrimination and prejudice in a society marked by racial division and hostility, their presence in the wrestling world challenged the status quo, evoking fears among some segments of the population who were resistant to multiculturalism and diversity – namely groups such as the National Front. However, the ‘Caribbean Sunshine Boys’ also arguably represented a beacon of hope and progress, breaking barriers and paving the way for greater racial inclusion in British society. Their success in the ring symbolised resilience and defiance against racial injustice, inspiring marginalised communities and challenging entrenched prejudices. Through their performances and eventual continued individual performance efforts, they forced audiences to confront their fears and confrontations, ultimately contributing to the ongoing dialogue on race and identity in 1970s Britain.

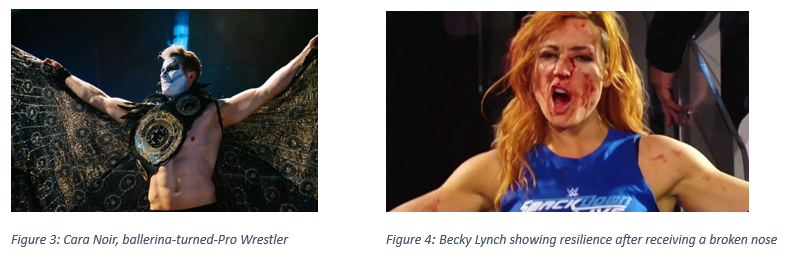

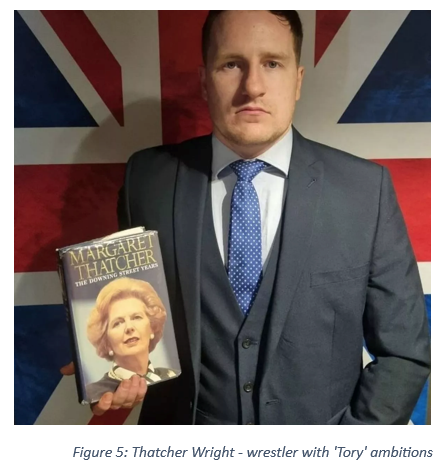

Nowadays, wrestling performers tend to reflect a more aspirational and multicultural audience than ever before. With successful characters on the independent British wrestling scene such as Cara Noir,– a much more diverse range of identities are being experienced by audiences, challenging the traditional, typical presentations of fighting performance and masculinity, giving way to a new wave of representation for future generations of both performers and fans. Women particularly have seen a much wider level of representation in modern wrestling, transcending stereotypes, showcasing not only athleticism but also compelling narratives and characters. This broader representation has allowed female wrestlers to become symbols of empowerment, resilience, and self-determination for audiences worldwide, particularly for female fans. On November 12, 2018, during an episode of WWE’s Monday Night Raw, Becky Lynch delivered one of the most iconic moments in modern wrestling, showcasing the empowerment of women in the sport. During a brawl, Lynch suffered a broken nose and a concussion after a punch from Nia Jax. Despite the severe injury and blood streaming down her face, Lynch continued to fight, embodying resilience and strength. Instead of retreating, she stood triumphantly in the crowd, arms raised, bloodied but unbowed, with a fierce expression that became an enduring image of determination. This moment transcended the scripted nature of professional wrestling, as Lynch’s grit and refusal to back down resonated with fans worldwide.

Lynch’s display of toughness drew parallels to the legendary match between Stone Cold Steve Austin and Bret Hart at WrestleMania 13. In that bout, Austin, despite excessive bleeding from a severe head wound, refused to submit, eventually passing out from the pain. This moment symbolised his unyielding determination and resilience, earning him the admiration and support of the fans, and cementing his status as a wrestling icon. Similarly, Lynch’s perseverance and defiance in the face of injury underscored her tenacity, capturing the hearts of the audience and elevating her status within the wrestling world.

This moment personifies Barthes’ notion of wrestling as a semiotic “performance of suffering,” where the display of pain and endurance plays a crucial role in the narrative. Lynch’s empowerment is highlighted through her presentation of resilience in the face of suffering, a process typically reserved for male performers and rarely seen for female ones. By enduring and overcoming visible pain, Lynch not only broke physical barriers but also shattered symbolic ones, showcasing that women in wrestling can embody the same heroic qualities of strength and perseverance.

However, it’s important to acknowledge that Lynch’s adoption of the moniker “The Man” to signify her dominance and top status in WWE is not without its criticisms. While it reflects her ascent to the pinnacle of professional wrestling, the term can be seen as problematic. It aligns with post-feminist ideals that suggest empowerment is achieved by adopting traditionally masculine traits and titles, which can inadvertently reinforce gender norms rather than dismantling them. Despite this, Lynch’s moment of bleeding yet standing tall remains a powerful symbol of women’s empowerment in wrestling, demonstrating that female wrestlers possess the same grit, determination, and resilience as their male counterparts.

Much like poetry, where symbolism often conveys deeper meanings and universal truths, wrestling personas symbolise wider beliefs or societal issues. Lynch’s bloodied visage and unyielding spirit symbolised a broader narrative of resilience and empowerment. Just as poets use vivid imagery and metaphor to evoke emotional and intellectual responses, Lynch’s real-life “performance of suffering” served as a powerful symbol of endurance and strength, resonating deeply with audiences and adding a rich, symbolic layer to the storytelling in professional wrestling.

——————————————————————————————————————–

T: Poetry, perhaps the most abstract of the three disciplines, channels symbolism through the power of language. Poets, like fighters, engage in a form of combat, wielding words as their weapons. From the epic verse of Homer to the existential musings of T.S. Eliot, poetry spans the spectrum of human experience, capturing moments of triumph and tragedy with equal fervour. Many poets, such as Lord Byron and Arthur Rimbaud, led lives marked by tumult and conflict, mirroring the struggles of the pugilist and the wrestler.

In the poetry of Dylan Thomas, we find echoes of the pugilistic spirit, as he famously declares, “Do not go gentle into that good night, Old age should burn and rave at close of day; Rage, rage against the dying of the light.” Here, Thomas summons the imagery of battle to confront the inevitability of death, urging defiance in the face of mortality.

Similarly, in the work of William Wordsworth, nature becomes a metaphorical arena where the human spirit contends with the elements. In “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud,” Wordsworth writes, “For oft, when on my couch I lie, In vacant or in pensive mood, They flash upon that inward eye, Which is the bliss of solitude; And then my heart with pleasure fills, And dances with the daffodils.” Here, the poet’s solitary contemplation becomes a form of spiritual combat, as he grapples with the transient nature of existence.

In conclusion, the symbolism between boxing, British wrestling, and poetry underscores the universal themes of human struggle and resilience. Whether in the ring, the squared circle, or the written word, these disciplines offer avenues for exploration and expression, transcending mere physicality to evoke deeper truths about the human condition. As Dr Dave Boyd’s research illuminates, the interplay between culture, history, and performance yields insights into our collective psyche, reminding us that the stories we tell are as enduring as the struggles we face.

——————————————————————————————————————–

D: Wrestling can provide a means of escape, but also a sense of solidarity and community for its viewers. On the performance side, wrestlers can become figureheads for movements including those signifying resistance or simply perseverance against the power structures which cause them struggle. We live vicariously through their struggle and subsequent victories. In poetry, we also have witnessed such creative outputs of resistance, such as Kentish War poet Siegfried Sassoon who symbolised his journey into pacifism and anti-war stance through the symbolic and stylistic qualities of his writing. Catharsis in wrestling, like poetry, offers emotional release and clarity. Both forms provide a safe space for audiences to confront and process intense feelings. Whether through physical combat or lyrical expression, they evoke cathartic experiences that resonate deeply with human emotions and experiences. Through their creative work, wrestlers and poets alike create a shared space where audiences can confront their own emotions, find solace in collective experiences, and ultimately emerge with a renewed sense of understanding and catharsis. Audience reactions, for example – whether cheers or boos, serve as barometers of societal sentiments. Ultimately, British professional wrestling acts as a microcosm of broader societal dynamics, offering both reflection and commentary on the values, conflicts, and aspirations of its audience and the culture at large.

To exemplify, controversial characterisations as traditionally observed in professional wrestling still exist on the scene to date, such as Thatcher Wright – a wrestler imbuing a sense of implied support of Conservative politics in his performance. The blatantly ‘Tory’, villainous Wright both acts as a symbolic figure representing current political unrest in the country, as well as providing a sense of catharsis for the audience when being beaten by the heroic ‘babyface’ or ‘good’ competitor. Despite problematic representations of race and nationality still being evident on contemporary professional wrestling, and those characterisations tending to evolve and shift societally, the connection stands between that of wrestling performance and poetry as ways of manifesting wider struggles and aspirations of their viewers and readers. This is reminiscent of how A.A Gill’s ‘The Angry Isle’ suggests argues that the English are characterised by a pervasive, often unspoken anger, stemming from deep-seated frustrations with social structures, historical grievances, and the perceived decline of their global influence. While this is quite a reactionary and reductive view overall, it intriguingly relates to professional wrestling, a sport that has historically provided a sense of catharsis and relief from everyday working-class struggles. Through its dramatic narratives and larger-than-life characters, wrestling offers an emotional outlet and a form of escapism that resonates with the underlying discontent. Even Kent Walton, renowned ringside commentator for the original ITV World of Sport wrestling broadcasts seems to observe this, noting in Simon Garfield’s classic book The Wrestling that the sports-based performance “provided a TV programme that almost everybody went for. […] It displayed aggression in its purest form and a conflict between good and evil in which sides could be easily chosen. This conflict was so basic that almost every viewer could identify himself or herself with it.” Lastly, Wrestling, much like the cathartic poetry explored by Hovey et al., provides an emotional outlet for the working class, offering a sense of relief and catharsis through its dramatic narratives. Both wrestling and poetry allow individuals to process and release their emotions, creating a space for psychological healing and insight. Thus, professional wrestling, with its symbolic struggles and victories, serves a similar therapeutic function, addressing and alleviating the underlying discontent Gill describes.

——————————————————————————————————————–

T: Embedded within the narrative of the boxing ring, British wrestling arena, and the realm of poetry, lies the personal journey of a boxing coach, once a competitive fighter, now a poet who continues to fight, albeit against different opponents. As a former boxer, the transition from the physicality of the ring to the intricacies of verse may seem like a departure, but in reality, it is a continuation of the same pugilistic spirit. The discipline and dedication honed in training camps now find expression in the meticulous crafting of words, while the strategic acumen developed in the heat of battle informs the poet’s approach to language and narrative. Yet, the fight continues, albeit in a different form. No longer confronting opponents in the ring, the poet now grapples with societal structures and entrenched ideologies, seeking to dismantle barriers and challenge prevailing norms. Each poem becomes a bout, a skirmish against injustice, inequality, and the tyranny of silence. In this new arena, the poet draws upon the lessons learned from years of training and competition, harnessing the power of metaphor and symbolism to provoke thought and inspire change. Thus, the journey from fighter to poet is not a divergence but a natural evolution, a testament to the enduring spirit of resilience and transformation.

Garfield, S (2013), The Wrestling. London, Faber and Faber.

Gill, A.A (2006), The Angry Island: Hunting the English. London, Phoenix.

Barthes, R. (1972). Mythologies. Translated by Annette Lavers. London, Paladin

Hoult E.C., Mort H., Pahl K. and Rasool Z. (2020) ‘Poetry As Method – Trying to See the World Differently’. Research for All, 4 (1): 87–101. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18546/RFA.04.1.07

Hovey R.B, Khayat V.C, and Feig, E (2018), ‘Cathartic Poetry: Healing Through Narrative’, The Permanente Journal, Vol.22. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/17-196

Thomas, D. (1951). “Do not go gentle into that good night.” In Collected Poems, 1934-1952 (pp. 124-125). New Directions.

‘When Wresting Was Golden: Grapples, Grunts and Grannies’ (2012), Timeshift, Series 12, Episode 6, BBC Four, 16th December.

Wordsworth, W. (1807). “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud.” In Poems in Two Volumes (Vol. 1, pp. 120-121). Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme

Image Credits:

Figure 1: Bleacher Report (2011), Big Daddy, available at: https://bleacherreport.com/articles/711139-wwe-kharma-and-wrestlings-50-biggest-behemoths-of-all-time

Figure 2: Wrestling Furnace (n.d), https://wrestlingfurnace.site/galleries/k/kincaid/kincaid13.jpg

Figure 3: Daily Star (2022), While the character of Cara Noir has strands of ballet and Swan Lake running through it, there’s nothing ballet-like about the in-ring action. Available at: https://www.dailystar.co.uk/news/latest-news/progress-wrestling-champion-talks-post-26499430

Figure 4: Wrestletalk (2021), BECKY LYNCH HAS NO MEMORY OF ICONIC WWE MOMENT. Available at: https://wrestletalk.com/news/becky-lynch-has-no-memory-of-iconic-wwe-moment/

Figure 5: Daily Record (2023), Thatcher Wright Uses a Margaret Thatcher Book Often As a Weapon Available at: https://www.dailyrecord.co.uk/in-your-area/lanarkshire/thatcherite-wrestler-says-rutherglens-in-30570460

The Poetic Nursing Heart

The Poetic Nursing Heart Jack Charter

Jack Charter 2407

2407