Aphra Behn

This March we’re celebrating all the women who tell our stories – women past and present whose words have moved, inspired, entertained, and above all changed the way we view the world around us. Aphra Behn was the first woman to achieve fame and success as a playwright, writing and staging at least eighteen plays on the Restoration stage to wide acclaim, indeed, counting royalty among her biggest fans. Besides her passion for the theatre, she was also a prolific writer of poetry, novels and translations of French works, too. The popularity of these works and her plays made Aphra the first woman in England to ‘live by her pen’. Let’s celebrate Aphra’s remarkable life and works this Women’s History Month!

Life & Times (1640-1689)

Aphra (or Eaffrey as she appears in some records) was born to Bartholomew Johnson and Elizabeth Denham in Harbledown, a small village on the outskirts of Canterbury, and baptised at a local church on 14 December 1640. What role, if any, Bartholomew played in his daughter’s upbringing remains something of a mystery. Elizabeth meanwhile was a wet-nurse for a distinguished family of Kent, the Culpepers, and it is likely that Aphra benefitted from these connections both in terms of her education (after all, Aphra could not attend King’s School like her male counterparts) and later as a way into fashionable society and theatres in London. While relatively little is known about Aphra’s early life beyond these few speculative details, we do know that she was born into a tumultuous period and lived through massive upheavals in society and government. In 1642, the English Civil War broke out, a struggle which lasted nine long years. The execution of King Charles I ushered in a new political era – a republic led by Oliver Cromwell. Teenagers like Aphra, however, probably found this new age a lot less exciting, especially when Cromwell closed the theatres and announced bans on everything from sport to Christmas. But by adulthood this had been reversed: Charles II was crowned king and the monarchy was restored – and with him came a resurgence of the arts.

In her mid-twenties, England was once again at war with the Dutch Republic. Evidently eager to prove her loyalty to the newly restored king, Aphra began working in Antwerp as a government agent for the crown. Being a woman proved to be the perfect disguise – the very fact Aphra was overlooked and underestimated because of her gender allowed her to gather information about overseas plots against the king. This intelligence she concealed by creating her own alphabet and code, signing off as ‘Astrea’ in her letters, a name she would go on to publish under in the literary world.

But Aphra returned to England a poor woman (spying, it turns out, was not a very lucrative career) and, not only that, she was a widow. Within months of marrying her husband, who was probably a Dutch or German merchant, Johan Behn had succumbed to the Great Plague of 1665-1666. Penniless and desperate, Aphra turned to writing and, above all, to the stage. Here, she thrived and found herself in close circles with the most famous writers of the day, including John Dryden and Edward Ravenscroft.

Aphra’s literary career was cruelly cut short by poor health. The Widdow Ranter was the last play she wrote before she died on 16 April 1689, aged only 49. Aphra was buried at Westminster Abbey, although sadly not in Poets’ Corner.

Work & Themes

Some Hands write some things well; are elsewhere lame;

Charles Cotton, “To the Admir’d Astrea” (1689). The sock and buskin are two ancient symbols of comedy and tragedy. Extract from J. Lipking, Aphra Behn: Oroonoko (London, 1997), p. 189.

But on all Themes, your Power is the same.

Of Buskin, and of Sock, you know the Pace;

And tread in both, with equal Skill and Grace.

The Restoration marked a turning point for women in the arts. For the first time, women were allowed to become stars of playhouses and the literary world in their own right. Female authors burst onto the scene while theatres saw the emergence of an entirely new role, that of the actress. In this way, theatres (and the artistic scene in general) did not only reopen in the Restoration period, they reopened transformed.

It was this new world that Aphra stepped into. She began writing poetry, pindaric odes as well as many pastoral elegies. These poems were often rather bawdy, as was the style of the time. The Disappointment remains her best-known poem for this very reason. Her explicitly lesbian love poetry, moreover, has made her something of an icon in the LGBT community today. Her first play, The Forc’d Marriage, was performed in 1670 by the Duke of York’s Company at Lincoln’s Inn Fields in London. She went on to write at least seventeen more plays which covered all sorts of genres. Ever the prolific writer, Aphra soon expanded into novels (publishing around seventeen in total) and produced several volumes of translations, too.

The Rover (1677)

This comedy is considered to be Aphra Behn’s most successful play, indeed, the Duke of York (the future King James II) enjoyed it so much he frequently ordered for it to be put on at court. The Rover is a bawdy yet subversive play which, like many of Aphra’s works, explores double standards in society and challenges gender roles through satire. The play follows a group of Englishmen who find themselves in Naples during Carnival, a topsy-turvy festival where normality was mocked and people let loose. Here, we meet our protagonist, Hellena, one of several strong female characters created by Aphra who subverts societal norms and speaks out against the patriarchy. Navigating the excitement and temptations of the Carnival through her wit and intelligence, Aphra presents Hellena as a woman in control of her own destiny and sexuality.

Many of the play’s ideas around gender and sexuality still resonate with us today, and is often read through a feminist lens. The Rover has since been adapted in many colourful and playful ways for modern audiences, including by the Royal Shakespeare Company at the Swan Theatre in 2016.

Oroonoko (1688)

Oroonoko signified a ground-breaking new form in literature – the novel. Unlike plays or poetry, novels were a lengthy work of fiction written predominantly in prose. It was a radical idea at the time and Aphra became one of its pioneers with Oroonoko one of the first publications in England to take this innovative form.

Oroonoko is now one of Aphra’s best-known works, not only for its literary form, but for its exploration of important themes such as colonialism, racism, and the brutality of slavery. The story follows our brave hero, Oroonoko, an African prince, who is enslaved by the English and brought to Surinam, a British colony in South America. Here, he is reunited with his long-lost lover, Imoinda, who has also been enslaved and subjected to brutal treatment at the hands of the English. Oroonoko and Imoinda live as husband and wife in their own slave cottage but, stifled by their lack of freedom, Oroonoko leads a revolt against his masters. While putting up a courageous fight, Oroonoko ultimately meets a tragic and very bloody end.

Whether Oroonoko may be as true a history as Aphra boldly claims (the full title of the novel is Oroonoko, or, The Royal Slave. A True History) is something that has been fiercely debated by scholars. Some, like M. Duffy, argue Behn actually visited Surinam in her early 20s and it was this trip which inspired the later novel. Others contest that Oroonoko is purely a work of fiction, demonstrating nonetheless the power of Aphra’s remarkable imagination. Fictional or not, it goes without saying that Oroonoko was very much a product of its time, reflecting and perpetuating many racial stereotypes already firmly established in literature. These harmful characterisations need to be discussed in their wider context and challenged. But while Aphra was complicit in many respects, Oroonoko also exposes the savagery of English colonial government and the inhumanity of the slave trade. It is a graphic and emotive depiction of the cruel realities of life in English colonies.

Silencing Aphra

Have you ‘ever seen Mrs. Behn’s novels?’ the old woman asked her great-nephew, Walter Scott – and could he retrieve a copy of the playwright’s works for her to read? The Romantic poet and novelist hesitated. After a long pause, Scott replied that while he could, he warned that he ‘did not think she would like either the manners, or the language’ she would find. Still the great-aunt insisted, recalling how much she had enjoyed reading these popular and delightful works in her youth. And so rather reluctantly Scott obliged, though he made sure to seal up the works in a packet marked ‘private and confidential’.

The next time he saw his great-aunt, Scott recalled her complete volte-face, how

she gave me back Aphra, properly wrapped up, with nearly these words: –

Sir Walter Scott in Lockhart’s Life of Scott (1837). Extract from Lipking, Aphra Behn, p. 194.

’Take back your bonny Mrs Behn; and, if you will take my advice, put her in the fire, for I found it impossible to get through the very first novel. But is it not,’ she said, ‘a very odd thing that I, an old woman of eighty and upwards, sitting alone, feel myself ashamed to read a book which, sixty years ago, I have heard read aloud for the amusement of large circles, consisting of the first and most creditable society in London.’

An amusing but very revealing anecdote. In little over a century, Aphra’s reputation had been utterly tarnished and her once popular works disparaged. Certainly, Aphra had faced criticism in her day for daring to write, above all about sex, but she had been able to confront her critics head-on; indeed often before publishing her texts, she would attach a prologue defending her honour and noting that her male counterparts did not receive such criticism. But as time went on, tastes changed and the bawdy style of Restoration literature (and the age in general) was increasingly seen as distasteful. More so, with a newfound emphasis on women writing in a feminine style (i.e. writing only on modest subject matters), Aphra’s works were considered vulgar and shocking. A new age of critics vilified her as a lewd woman who wrote works so immoral that they should not even be opened. And so, for over two centuries, Aphra and her achievements were erased from English literature.

Influence & legacy

All women together ought to let flowers fall upon the tomb of Aphra Behn, … for it was she who earned them the right to speak their minds.

Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

With the dawn of the twentieth century came a new open-mindedness. Moralising and gender expectations were put to one side and critics finally began to take her work seriously. In 1915, Montague Summers brought together and published many of Aphra’s works in a new six-volume collection and, in 1927, came a biography by Vita Sackville-West, Aphra Behn: the Incomparable Astrea.

But beyond scholarly circles, Aphra still remained little known to the wider public. That was until the feminist movement of the 1970s. This brought a new wave of interest in women’s writing and studying literature and history through a gender lens. There was a surge of activity surrounding Aphra Behn, including biographies, critical interpretations, republications of her work, journal articles, documentaries, and even the establishment of dedicated Aphra Behn societies. The Rover, moreover, has proved to be a hit in theatres ever since, with a new production out in playhouses every few years. Suffice to say, Aphra’s reputation has been restored to its former glory.

Aphra Behn is now studied by students at universities up and down the country. Her plays have become classic texts on modules exploring Restoration literature and theatre in the seventeenth-century, her poetry now analysed alongside other renowned authors of the age, while Oroonoko is often a staple text on postcolonial modules.

Today, interest in Aphra only continues to grow! There is still so much to learn and uncover about this fascinating figure and her writing.

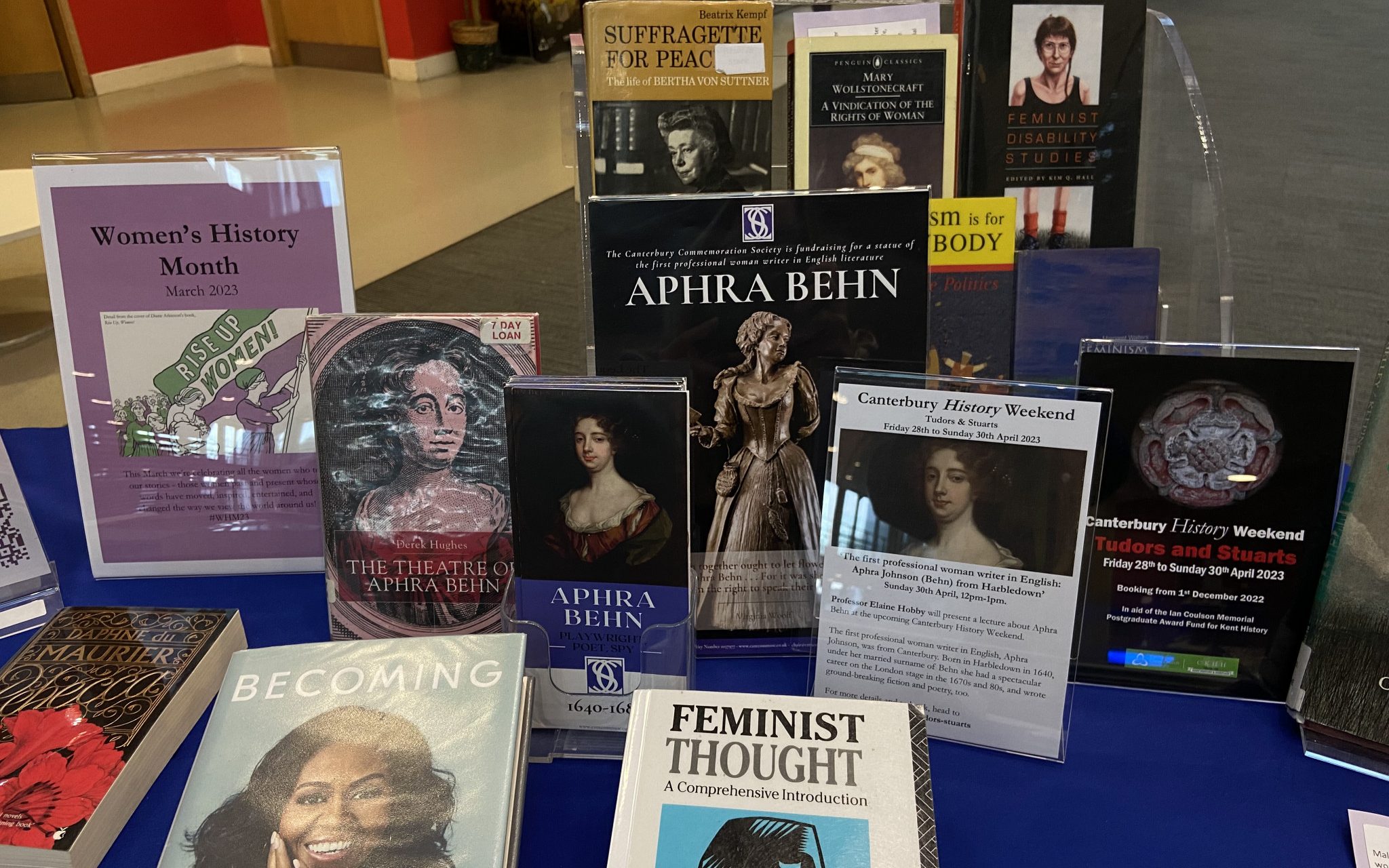

Celebrating Aphra’s connection to Canterbury

Over the last few years, there has been a surge of interest in Aphra Behn within the Canterbury community, her hometown. For a city that has long celebrated its ties to Chaucer and Marlowe, locals are keen to see this pioneering playwright take her place alongside these literary giants. The Canterbury Commemoration Society, for instance, is fundraising for there to be a statue of Aphra in the city. There are plenty of talks happening, too, including a lecture by Professor Elaine Hobby next month at our Canterbury History Weekend (student tickets are only £2!). This will culminate next year in one spectacular celebration – the Aphra Behn Festival. There is a fantastic line-up planned, ranging from various theatrical and musical events to an Aphra Behn Walk. It is also during this festival that the bronze statue of Aphra will be unveiled! At the same time, the Aphra Behn (Europe) Society will meet for its 8th international conference, Aphra Behn & her Restoration, at the University of Kent. So there’s a chance for everyone to get stuck in and celebrate Aphra Behn.

Resources

Whether you are a student of English literature, a history buff, or simply interested in learning more about this remarkable woman, there are many resources available at Augustine House (and online!) to find out more about the life and work of Aphra Behn…

Books in Augustine House – all found on the moving shelves unless otherwise stated

- Aughterson, K., Aphra Behn: the comedies (Basingstoke, 2003) 822.4 BEH

- Behn, A. & Todd, J. (ed.), Aphra Behn. Oroonoko : The rover, and other works (London, 1992) 823.4 BEH

- Duffy, M. (ed.), Five Plays (Reading, 1992) 822.4 BEH

- Duffy, M., The passionate shepherdess : the life of Aphra Behn, 1640-1689 (London, 1989) 822.4 BEH

- Goreau, A., Reconstructing Aphra: a social biography of Aphra Behn (Oxford, 1980) 822.4 BEH/GOR. Takes a feminist approach.

- Hicks, M., Aphra Behn: Selected Poems (Manchester, 1993)

- Hughes, D. & J. Todd (eds.), The Cambridge companion to Aphra Behn (Cambridge, 2004) 822.4 BEH [7 day loan]

- Hughes, D., The theatre of Aphra Behn (Basingstoke, 2001)

- Hughes, D., Versions of Blackness: Key Texts on Slaver from the Seventeenth Century (Cambridge, 2007) 820.9355 VER

- Iwanisziw, S.B. (ed.), Troping Oroonoko from Behn to Bandele (Aldershot, 2004). 823.4 BEH

- Lipking, J., Aphra Behn: Oroonoko (London, 1997) 823.4 ORO. See pp. 189-198 for Aphra’s critical reception before the revisionist turn in the ’80s.

- Spender, D., Women of Ideas and What Men Have Done to Them: From Aphra Behn to Adrienne Rich (London, 1982) 301.412 SPE

- Wiseman, S.J., Aphra Behn (Devon, 2007) 828.4 BEH

Box of Broadcasts (BoB)

- Harlots, Housewives and Heroines: A 17th Century History for Girls, Act III: At Work and At Play

- In Our Time: Aphra Behn

Other e-resources

- ‘A is for Aphra‘

- ‘Aphra Behn & her Restoration: 8th international conference of the Aphra Behn (Europe) Society‘

- ‘Aphra Behn Festival‘

- ‘Canterbury Commemoration Society‘

- ‘Canterbury History Weekend 2023‘

- ‘Oroonoko‘

- ‘The Rover at the RSC‘

- Todd, J., ‘Behn, Aphra [Aphara]: Janet Todd‘

- Woolf, Virginia, A Room of One’s Own (Rudolstadt, 2020), particularly Ch. 4.

Feature image credit: Alamy. Quotation in heading from Sir Patient Fancy, 1678.

Library

Library Irene Szmelter

Irene Szmelter 956

956