LGBT+ History Month

February is LGBT+ History Month. This year’s theme is Medicine #UnderTheScope. We’re joining in with the celebrations and sharing stories of historical figures within the medical profession. Today I will be sharing the inspirational, ‘Sophia Jex-Blake’. Sophia was one of a group of seven women who became known as the ‘Edinburgh Seven’. Their long campaign was for women to have the right to higher education and the ability to graduate and practise medicine in the UK.

Who was Sophia?

Sophia Jex-Blake was born on 21st January 1840 in Hastings, Sussex. Sophia came from an already prestigious family – her father worked as a lawyer. Sophia was able to attend private boarding schools and had a good education, where she excelled. She was aware she did not have to make a living to earn a wage but had already decided to train as a schoolteacher.

At 17 years old, she entered Queen’s College in Harley Street, established back in 1848 and still a thriving college today. Richard Tillett, current principal for the college states:

“Queen’s was the first British educational establishment to give academic qualifications to women” (Tillett, 2024).

Sophia entered Queen’s College and undertakes a teacher training course specifically for women. In her article, ‘Education and Sex’. Burstyn says:

“With the opening in London of Queen’s College, Harley Street, and the Ladies’ College, Bedford Square at the end of the 1840’s, a quiet revolution in the education of governesses and teachers had begun.” (Burstyn, 1973)

Burstyn adds,

“Neither of these institutions offered a full-time university course; each had to act as a school as well as an institution of higher learning. Yet the education they gave was invaluable in raising the standards of women’s education throughout the county” (Burstyn,1973)

The influx of women undertaking training in colleges like Queens, and subsequently leaving to become governesses and schoolteachers, led to an increase in the supply of well-educated female teachers which in turn raised the standard of education in the country.

While Sophia was undertaking teacher training at Queen’s College, she also undertook private tuition in Edinburgh. While in Edinburgh, Sophia met Elizabeth Garrett-Anderson. Elizabeth was preparing to enrol to study medicine in Edinburgh.

From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository

This meeting was to change Sophia’s ambitions. Sophia decided she too wanted to study medicine.

You can find out more about Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and her own struggles while entering the medical profession here: CW+ Women in Medicine (Lawes,2024).

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson. Photograph by Swaine. Sourced: Wellcome Mooo5667.jpeg

Attitudes to women entering the Medical Profession in the 1870s and the Society of Apothecaries

At this time, women were not allowed to undertake degrees to enable them to enter the medical profession. A few were able to enrol and go to lessons but were not able to pursue their ambition of becoming a practising doctor due to not being able to undertake the exams they needed to qualify.

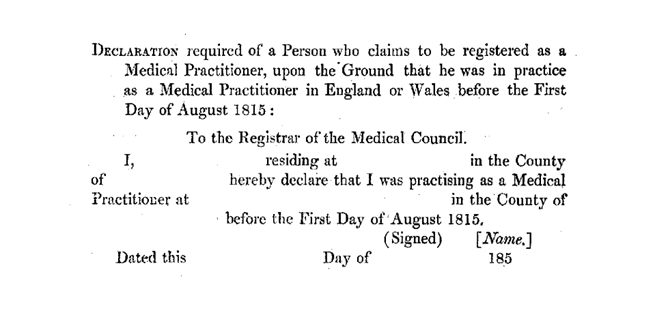

Under the 1858 Medical Act, newly qualified physicians had to have their names entered onto a register to be able to set up a practice as a GP or work as a physician. In 1865 just two names were entered on the register belonging to female candidates.

The above images have been sourced from Legislation.gov.uk Medical Act 1858 Chapter 90. Accessed online 26/07/2024.

When the Society of Apothecaries, (the establishment where medical exams were invigilated and processed), learnt of its error in allowing two women to pass the exam necessary for registration, they then made it impossible for women to take these exams.

“no candidate should be examined who had been privately educated, for it was well known that no woman would be admitted to the regular courses and classes at which men obtained their education” (Porritt, 1919)

Society of Apothecaries

Society of Apothecaries coat of arms.

Above are the coat of arms for Society of Apothecaries located on the building.

The Society of Apothecaries took steps to prevent women from obtaining registration by making certain compulsory courses within the medical syllabus closed to women. This in turn prevented women from undertaking the full courses and exams that would enable them to become fully qualified physicians.

The ‘Edinburgh Seven’

In 1869 Sophia and four other women enrolled into the University of Edinburgh. They became the first five women to join as medical students at a British university. By the end of the year an additional two women joined the university. The group of seven women became known as ‘Edinburgh Seven’.

The Edinburgh Seven were:

Sophia Jex-Blake

Isabel Thorne

Edith Pechey

Matilda Chaplin

Helen Evans

Mary Anderson

Emily Bovell

When the seven women applied to the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary so they could undertake medical training, their applications were all rejected.

Professor of medicine Robert Christison, himself a renowned physician, and others believed:

“This would be lower the standing of the profession” (Ellis, 2012)

Other faculty members were said to believe the same. There was an outcry within the male student body, as they also felt that to allow women onto the course would lower the reputation of school.

Kristine Swenson in her book, “Medical Women and Victorian Fiction” describes the contemporary opinions of male medical practitioners:

“The medical establishment’s most powerful weapon against the threat came from its own “scientific” findings that suggested that women were unsuited for the intellectual and physical work involved”

Swenson, (2005) p. 86-87.

Swenson goes on to detail one of the male physician’s ideas of women who wanted to become doctors:

“Many of the most estimable members of our profession perceive in the medical education and destination of women a horrible and vicious attempt deliberately to unsex themselves – in the acquisition of anatomical and physiological knowledge the gratification of a prurient and morbid curiosity and thirst after forbidden information – and in the performance of routine medical and surgical duties the assumption of offices which Nature intended entirely for the sterner sex”

Swenson, (2005) p. 86-87.

You can find out more about Medical women within, ‘Medical women and Victorian Fiction’ by Kristine Swenson. Discoverable via LibrarySearch.

Medical Women and Victorian Fiction by Kristine Swenson.

The Surgeons’ Hall riots: a turning point for the Edinburgh Seven

It was 18th November 1870, the day of the anatomy exam for Sophia and her fellow students. The exam was always undertaken within the Surgeons’ Hall, Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, Scotland.

Surgeons’ Hall, Edinburgh.

The image above was sourced by Wikimedia commons Surgeons Hall by Paul Gillett, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

When the female students tried to enter their exam, they were met by a large crowd made up of their male student peers. Several were drunk, and hurled verbal abuse and mud at the women.

Sophia describes the event in her own words:

“On the afternoon of Friday 18th November 1870, we walked to the Surgeons’ Hall, where the anatomy examination was to be held. As soon as we reached the Surgeons’ Hall we saw a dense mob filling up the road… The crowd was sufficient to stop all the traffic for an hour. We walked up to the gates, which remained open until we came within a yard of them, when they were slammed in our faces by several young men”. (Sophia Jex-Blake)

Once the exam started, it was continually interrupted. One instance saw the college sheep, named Poor Mailie, let loose into the exam hall. Once the exam had finished, the women were met with more abuse, with more rubbish and mud being thrown at them. They were escorted home by a group of supportive male students, who were later known as the ‘Irish Brigade’.

This incident was recalled as an appalling event and the community was shocked to have such a situation occur towards a group of women. Newspapers, including The Scotsman, wrote articles describing what happened and the abuse and anger the women were submitted to.

“all men to come forward and express their detestation of the proceedings which have characterised and dishonored the opposition to ladies pursuing the study of medicine in Edinburgh” (The Scotsman)

Sophia was called to court and proceedings were set against her for ‘defamation of character’ by Mr Craig who, interestingly, was Professor Christion’s classroom assistant. Mr Craig himself was named as the leader of the riot. Unfortunately, Sophia lost her case to Mr Craig and was ordered to pay one farthing in damages! Sophia and her colleagues, the ‘Edinburgh Seven’, considered this to be a small win against her opponents. This kindness towards Sophia, as someone who lost a defamation case, especially within these circumstances, was not usual then. The Surgeons’ Hall riot was despicable, and the news coverage helped their cause. Working women from all areas of employment were now following the ‘Edinburgh’s Sevens’ story and joining in with the campaign for the right of women to become physicians.

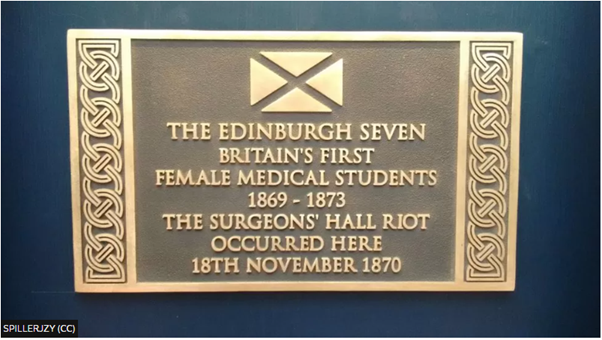

There is a plaque outside the Surgeons’ Hall, with the date and location of the riot, commemorating the bravery of the Edinburgh Seven.

Plaque outside the Surgeons’ Hall.

Image above sourced by Wikimedia commons Spillerjzy, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Edinburgh Seven continued to demonstrate. They wrote to the newspapers and brought cases against the university. In 1873, after a long battle, the courts decided that the admission of women was beyond its powers and therefore women were still not eligible to graduate with medical degrees.

What was next for Sophia and her friends?

The Edinburgh Seven all left for London and Sophia Jex- Blake founded the ‘London School of Medicine for Women’.

London School of medicine for women.

Image above is sourced via Flickr licensed under Creative commons created by Royal Free Archive Centre.

For the school to become established they needed partners in education to support the examinations. In 1876 the College of Physicians in Dublin agreed to admit women for examinations and in 1877 the London Free Hospital in Gray’s Inn Road began teaching female medical students.

What was next for Sophia?

Sophia never gave up. She travelled to Switzerland, where she graduated with an MD from University of Berne in 1877. She passed her examinations in Dublin and qualified as a medical practitioner in May of the same year. In 1878, Sophia opened a medical practice in Edinburgh and established an outpatient clinic for deprived members of the community. The medical schools and women that ran hospitals were to be key figures in the small network of first-generation medical women.

In 1885 The Royal Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons of Edinburgh changed their rules and gave women the right to take part in the examinations to enable them to become doctors.

Sophia wrote in one of her letters to her friend Lucy Sewell:

“It is a grand thing to enter the very first British University ever opened to women, isn’t it?”

In 1886 Dr Sophia helped to open Edinburgh School of Medicine for women, where approximately 80 women were educated. It was still to be another eight years before women were admitted to study medicine. Dr Sophia also met her life partner Dr Margaret Todd in the same year. Together, they wrote several crucial articles in favour of women’s suffrage and women’s importance to the medical profession. Dr Sophia Jex-Blake passed away from heart failure on 7th January 1912.

Sophia Jex-Blake.

The above image was sourced by Wikimedia commons Sophia Jex-Blake authored by Margaret Todd, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

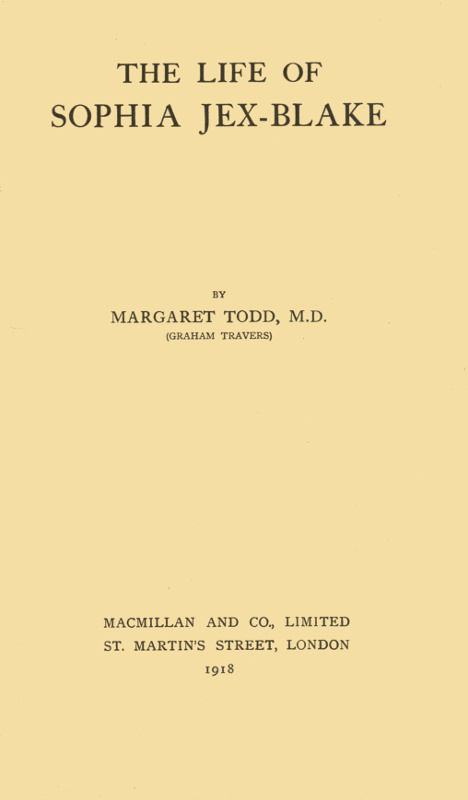

Dr Sophia’s partner, Dr Margaret Todd, wrote a book dedicated to Sophia, titled ’The Life of Sophia Jex-Blake’. The book describes both their struggles and experiences trying to enter the medical profession. Dr Margaret pays tribute to her partner’s strength and determination.

Annie G. Porritt, reviewer of Dr Todd’s book said:

“Somewhat headstrong temperament injured her in public estimation” Within the book, she explains, “without the strength and the fighting spirit so strongly present in Miss Jex-Blakes character, the fight could never have been won, and that English and Scotch women might have had to wait many years longer”. Porritt, (1919)

The Life of Sophia Jex-Blake cover.

You can find a review and article by Annie G. Porritt by searching within LibrarySearch and selecting for jstor from the Databases A-Z tab.

An online copy of the book is available via Google Books.

In her article, Annie makes the following statement.

“It was the battle that had been waged by Dr Sophia Jex-Blake that made possible the heroic service of Dr Elsie Inglis and of the great company of women doctors who served in the military hospitals of the Allies between 1914 and 1918” Porritt, (1919).

This is another reason why we must thank and appreciate Sophia, the Edinburgh Seven and all the medical women who invested their time in fighting for the right to become doctors. World War One was coming, and history could have been very different without them.

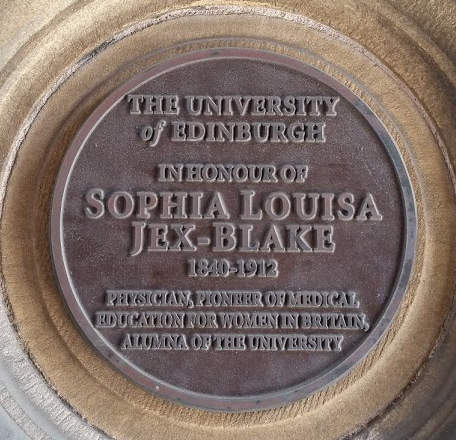

Dr Sophia Jex-Blake’s legacy

I think we must thank Dr Sophia Jex-Blake for her bravery and her tenancity, and her colleagues in the Edinburgh Seven for campaigning for women to have an equal right to higher education. The shift in professional ideals and personal and sexual identities was reflected in Dr Sophia’s long relationship with Dr Margaret Todd. It is important we remember the sacrifices made by women like Dr Sophia and the Edinburgh Seven as they led the way to push for change for women within society both professionally and personally.

Plaque located on the walls of The University of Edinburgh.

Sourced by gnomonic, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Sophia was courageous, some would say rebellious! Some have quoted her as tough with a hasty temper, but these were traits that she needed to fight her battles. She has been quoted as an honest woman determined and dedicated to the cause! Thank you, Dr Sophia Jex – Blake.

References and further reading.

Burstyn, J. (1973) ‘Education and Sex. The medical case against Higher Education for Women in England, 1870-1900’, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 117(2), pp. 79-89.

BBC History (2024) Elizabeth Garrett Anderson 1836-1917. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/garrett_anderson_elizabeth.shtml (Accessed: 24 January 2024).

BBC News (2019) Edinburgh Seven doctors to graduate after 150 years. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-edinburgh-east-fife-47814747 (Accessed: 26 January 2024).

BBC News (2018) Sophia Jex-Blake. The battle to be Scotland’s first female doctor. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-edinburgh-east-fife-46180368 (27 January 2024).

Carter, A. (2024) ‘Queer women in the history of medicine: Sophia Jex-Blake and women’s medical education in Victorian Britain’, University of Toronto Libraries Thomas Fisher rare book library, 21 June. Available at: https://fisher.library.utoronto.ca/fisher-blog/queer-women-history-medicine-sophia-jex-blake-and-womens-medical-education-victorian (15 January 2024).

Ellis, H. (2012) ‘Sophia Jex-Blake: the first woman medical graduate to practise in the UK’, British Journal of Hospital Medicine, 73(3),

Lawes, S. (2024) C+ Women in Medicine. Available at: https://www.cwplus.org.uk/about-us/heritage/300-years-of-chelsea-and-westminster/women-in-medicine/ (Accessed: 30 January 2024).

Porritt, A G. (1919) ‘Reviewed works: The Life of Sophia Jex-Blake by Margaret Todd’, Political Science Quarterly, 34(1), pp. 179-181.

Riad, A. (2020) ‘The Surgeons’ Hall Riot, Edinburgh Medicine Timeline, 20 April. Available at: https://blogs.ed.ac.uk/edmedtimeline/the-surgeons-hall-riot-a-turning-point/ (Accessed: 27 January 2024).

Society of Apothecaries (2024) The Worshipful Society of Apothecaries. Available at: https://www.apothecaries.org/who-we-are/ (Accessed: 27 January 2024).

Swenson, K. (2005) Medical women and Victorian fiction. Edition. London: University of Missouri Press.

The University of Edinburgh (2021) Centre for Biomedicine, self and society. Available at: https://www.ed.ac.uk/usher/biomedicine-self-society/blog/the-hidden-lgbt-history-of-the-edinburgh-medical-s (Accessed: 26 January 2024)

Queen’s College (2024) Welcome from Queen’s College. Available at: https://www.qcl.org.uk/ (Accessed: 27 January 2024).

Featured image: of Sophia Jex-Blake by Margaret Todd, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons sourced by Royal Free Hospital

Library

Library Vicky Mason

Vicky Mason 2386

2386