Peter Joyce explores the library’s archives and special collections and finds Book of Common Prayer that piques his interest . Read on to find out why…

The hustle and bustle of the library in Augustine House to me, has always been an indication of the health of the university and is always a good place to stop, chat and reflect on the everyday strains and stresses of institution life.

On a recent visit, I bumped into Michelle Crowther and her amazing team of volunteers who look after the institution’s archives. Whilst talking about their work and the incredible work that students do on their digital humanities placement, I was kindly shown around the archive. Being a bit of a bibliophile, I have to say their collection of older books was far more interesting to me than the brown and grey boxes that adorn the shelves filled full of the correspondence of noted luminaries like Mary Elizabeth Braddon or the institution’s history.

As we walked through, I soon noticed a collection of theology books including what looked like an old bible. Now as a collector of bibles, the chance to pick up and explore a bible isn’t one that I was going to pass by. In my experience, a bible is a much-overlooked window into social history. Old family bibles often have notes of major family events and are quite often littered with newspaper cuttings or notes. These keepsakes which are left between the pages of favourite verses are often disposed of with the bible by a later generation who for whatever reason feel no attachment to the text and give them away to charity shops with the keepsake still inside all but forgotten.

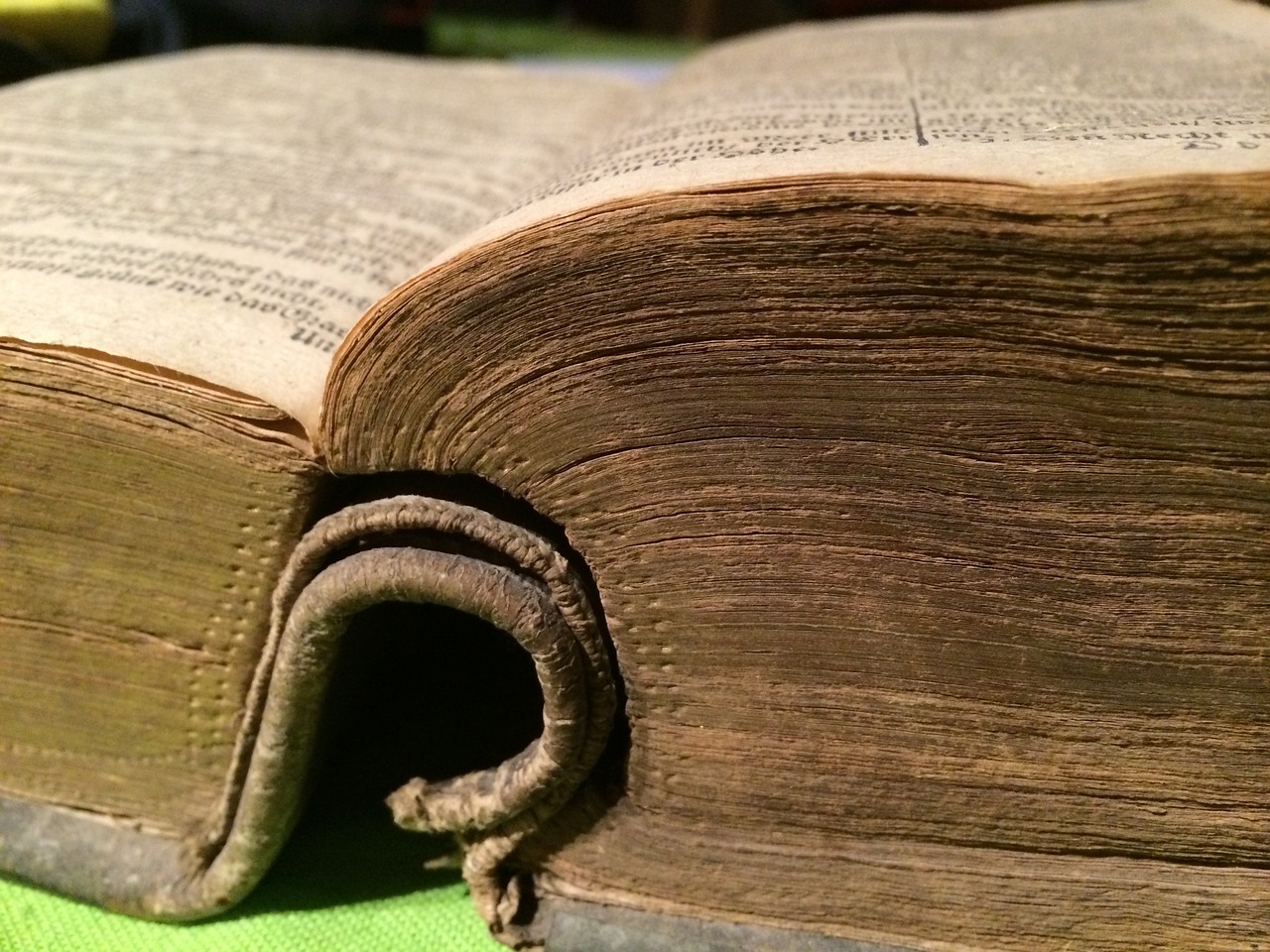

As many colleagues who have worked in archives or with old texts will know, you develop what can only be described as a sixth sense. As soon as you pick a book up, the weight, smell and feel all start to guide you towards an age. Then as you start to explore the page, instinctively you assess the text quality, the typeface and the page weight. Any marginalia is quickly observed as your eyes dart over the page in a scanning motion, looking for clues to the type of writing instrument, the ink type and any obvious connection with the book’s previous owner and slowly at first but with the quickening of the heartbeat you realise that whatever it is you’ve picked up is not your ordinary run of the mill library book………… Maybe that’s me being an old romantic but that has always been my experience and why I believe some books feel like a pair of comfy slippers and others like a pair of jeans that need letting out a few notches.

Viewing the BCP in the Archives

In this case, I knew I was into a comfy pair of slippers but not the ones I expected. What I had thought was a bible while it was laid on the shelf turned out to be a Book of Common Prayer (BCP). The BCP was in common use in the Church of England until c.2000, since then its use has declined. First introduced by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer in 1549, the BCP has been the backbone of the Anglican Communion ever since. Over the years it has gone through several revisions, most notably 1662 which is the accepted standard version still used with some minor adjustments. This history of the BCP is complex but each monarch from Edward VI to Charles I demanded that various adjustments were made to promote their particular theology. There was a proscription of the BCP after the Parliamentarians’ victory in the civil war which lasted until the restoration in 1660 leading to the 1662 version. Attempts to substantively change it in 1688 to unite the Puritans with the church were rejected and in 1928 parliament rejected a further attempt at revision, the first since 1688[1].

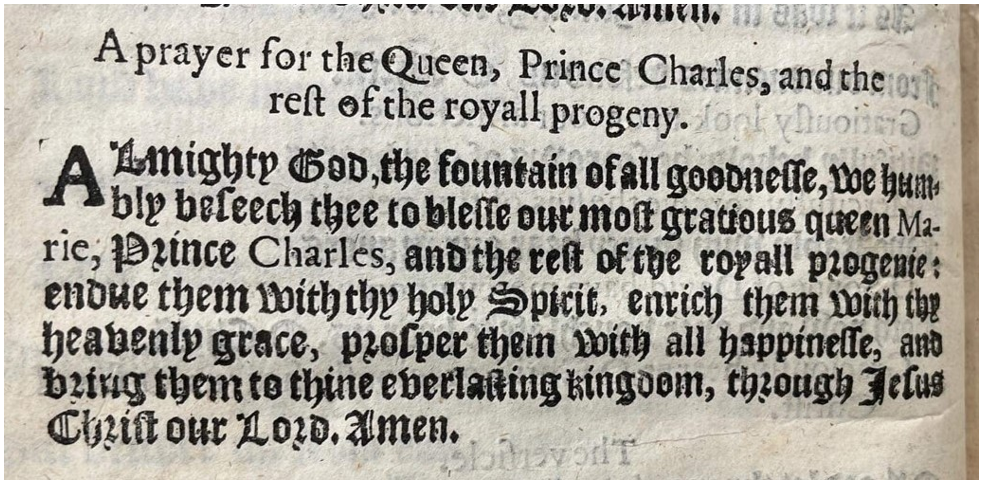

Dating a BCP is a matter of elimination which generally means that accurate dating before the 20th century can be at times nearly impossible. Like all these things there are BCP scholars who know nuanced changes that they can detect but for most people, the simple guide is to look at A prayer for the sovereign (or the fourth collect) which can be found at the end of morning or evening prayer. This prayer currently includes the line “Most heartily we beseech thee with thy favour to behold our most gracious Sovereign Lady, Queen Elizabeth…” The name of their Most Gracious Sovereign printed here will be the best clue, as dates that monarchs are on the throne are easily obtained. However, there are drawbacks, for instance, is it Elizabeth 1 or 2 and the same for George, Charles, James etc. In that case, we must turn to A prayer for the Royal Family. This prayer immediately follows the previous prayer and until the passing of HRLH Prince Phillip read “…we humbly beseech thee to bless Phillip Duke of Edinburgh, Charles Prince of Wales…” The combination of the two should date, quite reasonably, most prayer books. After that, it is a case of more detailed knowledge of when collects were removed. For instance, the famous collect for the 5th of November “O LORD, who didst this day discover the snares of death that were laid for us, and didst wonderfully deliver us from the same; Be thou still our mighty Protector, and scatter our enemies that delight in blood. Infatuate and defeat their counsels, abate their pride, assuage their malice, and confound their devices…” was removed in 1858 after petitions by the Earl of Stanhope. One of the other factors in dating this BCP was the use of black type in the printing. While this type of printing remained in Germany until after World War II in England it had started to be obsolete by the 1700 and had almost completely disappeared from regular use by the mid-eighteenth century.

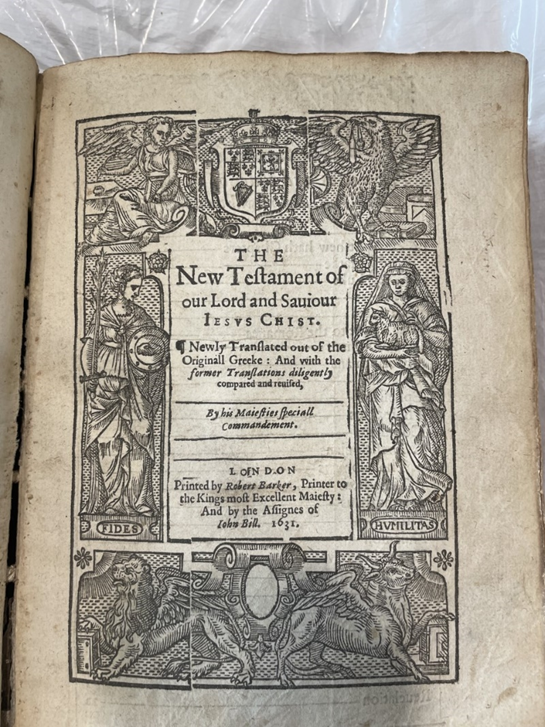

In this particular case, the fourth collect read “most hartely we beseche thee with thy favoure to beholde our most gracious soveraigne Lord King Charles” and the prayer for the Royal Family was “…we humbly beseech thee to bless our most gratious queen Marie, Prince Charles and the rest of the royal progenie…” Meaning, that we can quite specifically date the prayer book to the reign of Charles I (1625-1649). However, that still left a window of 24 years during which some of the most important English histories happened. I wondered if it was possible to do better. Bound in with the BCP was a New Testament, printed by Robert Barker in 1631 and although I was tempted to accept that as a date, I still had my reservations. Research shows that despite Robert Barker being the King’s Printer and the original printer of what we refer to as the King James Version (KJV) of the bible in 1611, found himself in prison in 1635. Despite his role as the King’s printer, Barker was notoriously bad at proofing his work and one such error would cost him liberty. In 1631 Robert Barker and Martin Lucas printed a version of the KJV which omitted the word NOT in Exodus 20:14 so instead of the seventh commandment reading “Thou shalt not commit adultery” it reads “Thou shalt commit adultery” This bible also known as the Adulterous Bible or the Sinners’ Bible was labelled by James Lenox as the Wicked Bible at the June 1631 meeting of Society of Antiquaries of London, the name has stuck ever since. Only sixteen of these bibles are known to exist in the current day with most of them being destroyed at the time. Roughly a year after printing Barker and Lucas were fined £300 (about £42,983.82 in 2022). The inability to pay that debt and various other debts on the back of their printing misdemeanours landed them both in prison in 1635.

Therefore, we have now narrowed the possible date to 1631-1634. However, we can do better. You will have noticed that the prayer for the royal family contains the term progenie. This term, which is no longer in general use means “Offspring, issue, children; descendants. Occasionally: a child, a descendant; a family” (OED, 2022.). In the BCP collect for the royal family, this term was not added until after 1634 following the birth of James, Duke of York in 1633. This closes the dating window now to 1634 – 1635 a maximum of 24 months and I do not feel it is possible to do better than that.

To contextualise the journey that this BCP has been on since printing let us look at the events that have passed in its approximate 390 years of life: the martyrdom of Archbishop Laud who oversaw its revision, a civil war, a revolution, fifteen monarchs, two world wars, countless minor revisions and an unknowable number of owners. The fact it is lying on a shelf in the Augustine House library is a minor miracle in its own right. So, what for the future? Sadly, the BCP is in quite a damaged state and desperately needs conservation work that is expensive. Why should that be done? For a number of reasons: Firstly, its value as a historic artefact and its connection to the Anglican history of the institution. Secondly, it is unusual as it is printed or bound right at the cusp of Robert Barker’s imprisonment, so may represent his last-ditch attempt to avoid prison. Thirdly, because it warrants further scholarship. Its providence, if possible, needs to be established; it has the name of Elizabeth Campe as marginalia. Who was Elizabeth, what is her connection? Fourthly, it is possible based on Barker’s reputation that the 1631 New Testament was left on the shelf unused for three to four years because it contains errors, that need a careful and systematic approach to either confirm or discredit, as it may be vital to further biblical scholarship.

So next time you are in the library do not pass by when something catches your eye because you never know what journey into the past or future that object might take you.

Pete Joyce is a PhD scholar with CKHH looking at Parochial charity in the long eighteenth century in the lower Medway valley.

Image Credits:

Featured image: Image by Christian Fraaß from Pixabay

[1] For more on the history see Procter, F. (1902) A new history of the Book of Common Prayer: with a rationale of its offices London: Macmillan (264.039PRO); Parker, J (1877) The first prayer book of Edward VI. Compared with the successive revisions of the Book of Common Prayer: Also a concordance to the rubricks in the several editions. London: CofE (264.039CHU). There are a number of other highly recommended books on the BCP, possibly the best place to start is with The Prayer Book Society (www.pbs.org.uk).

Library

Library Michelle Crowther

Michelle Crowther 1898

1898

Very cool forensic work. Keep it up! — Ivan