From Dr Demetris Tillyris – Lecturer in Politics and International Relations at Canterbury Christ Church University.

The scale of the defeat of May’s Brexit plan aside, the outcome of the Brexit meaningful vote was hardly unexpected. With the exception of a small sect of Tory MPs who remain loyal to the Prime Minister (or, who pretend that they are), it was apparent that May’s plan was detested by all sides since its inception. Yet, the defeat of May’s Brexit agreement and the government’s survival of a no-confidence vote beg the following question: now what?

To suggest that politicians, from across the spectrum, are armed with an answer to that question would be to ignore the vacuity with which Brexit has been approached over the past 18 months. This is not to say that a number of options or possible outcomes do not exit. And, whilst some of these options might appear more viable than others, it would be imprudent amid our turbulent times to discount any of these (regardless of how imprudent and, indeed, disastrous some of these might be).

A No-Deal Brexit on March 29, which would see the UK revering to trading on World Trade Organization rules and which would put an end to frictionless trade, is likely, despite numerous warnings that such an outcome would be catastrophic for the economy, for jobs, for food supply and for health (amongst other things). Indeed, a No-Deal Brexit would be a certainty if no further action is taken, ifno second referendum or general election are held, and if no further deals are agreed. So if a No-Deal Brexit constitutes an unprecedented abdication of political responsibility, then how plausible are the aforementioned alternatives?

Whilst a Second Referendum might appear to constitute an answer to Remainers’ prayers, there is little guarantee that the public would deliver a different outcome (even if one assumes that the British demos is more informed about the European Union now, than it was in 2016), or that it would settle the matter once-and-for-all. Indeed, the worry here is that a second referendum will sow further division within an already polarised society, and further compromise the public’s capacity to distinguish between fact and fiction amid a political domain already ridden not with lies (conscious acts of deception and misrepresentation of the truth) but with bullshit (‘anything-goes’ statements which bespeak of disregard or indifference to the truth altogether).

An Article 50 extension, likely as it might seem, requires the agreement of the EU and will merely postpone the issue. But such a postponement would presuppose commitment to resolving the issue: an extension Article 50 would be possible only if it served a specific purpose or point – a second referendum or a general election; or, perhaps, buying some time in order to get the legislation through.

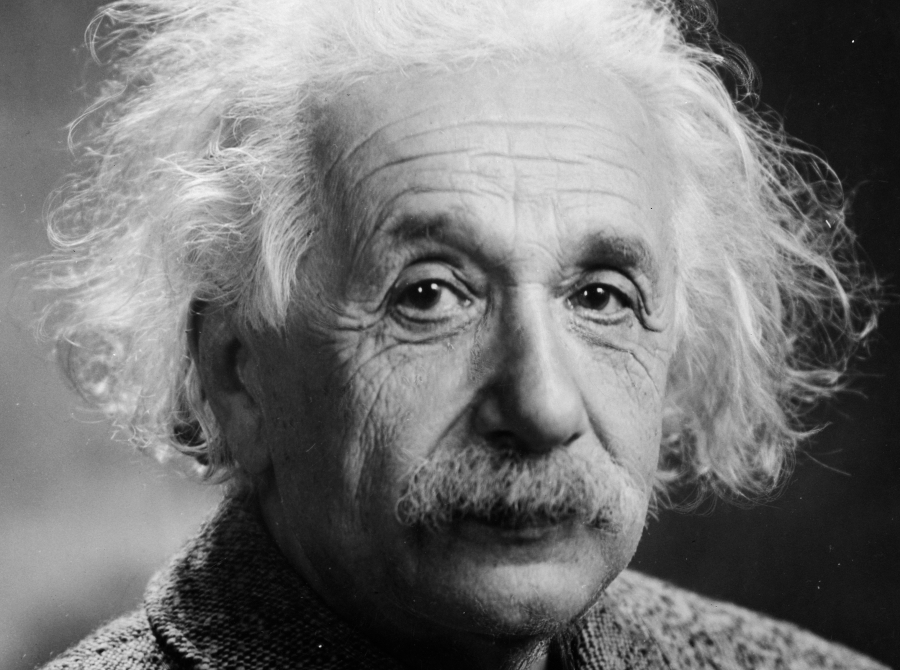

So, perhaps, the rejection of her Brexit agreement might compel May to return to Brussels, in the hope of securing a ‘better’ deal. This option seems to be favoured by hard-line Brexiters, who have suggested that May’s defeat has armed her with a ‘massive’ and ‘unmistakable’ mandate to renegotiate with the EU. The trouble is that statements of this sort, are fuelled by the unwarranted presupposition that the EU would be content to further stretch its already stretched red lines. Given that the EU-27 have been repeatedly emphasising since the day of the referendum what they can and cannot offer or compromise on, renegotiating on the same lines would constitute a manifestation of Einstein’s definition of insanity. Renegotiation would, in short, be purposeful only if broader issues, such as the customs union, are reintroduced to the table – a prospect which May has rejected. Given that a lot rests on what one means by a ‘better deal’ in the first place, and the irreconcilable differences in attitudes towards the EU and Brexit, securing a ‘better’ deal would require, at the very least, a plethora of politicians to suspend their obstinate quest for ideological purity for the sake of politics – to compromise some of their deeply-held convictions and aspirations. Without such compromises or renegotiation, it is difficult to see how a new deal would differ from the old deal, both in it terms of its content and fate.

Politics

Politics Christina Ackah-Annobil

Christina Ackah-Annobil 586

586