Dr David Bates is Principal Lecturer and Director of Politics and International Relations at Canterbury Christ Church University. His research and expertise focus on contemporary and radical political thought, Marxism, Hardt and Negri, Occupy, Arts and Politics, New Social Movements.

Dr David Bates is Principal Lecturer and Director of Politics and International Relations at Canterbury Christ Church University. His research and expertise focus on contemporary and radical political thought, Marxism, Hardt and Negri, Occupy, Arts and Politics, New Social Movements.

Until recently, political scientists often claimed that British politics had ceased to be ideological – by which they meant that it was no longer divided so clearly between left and right. The concomitant claim was that election battles were to be fought on the ‘centre ground’. As a social and political theorist, I have always found these claims to be deeply problematic.

First, we might note that those issues which typically underpinned left-right distinctions (that is, issues of economic distribution, of wealth and power) have continued to shape British politics.

Second, the centre ground as typically understood is a fiction. The idea of the centre ground is, in the minds of most people, associated with moderation, a middle way between ‘extremes’ – an Aristotelian mean. But as one writer has maintained, since the 1970s the fictitious centre is ideologically an extreme one. Put another way, extreme free market policies have come to be dressed in the clothes of pragmatic ‘common sense’. As the philosopher Slavoj Zizek has maintained, ‘post-ideological times’ are in fact the most ideological of times.

We have seen left-populist attempts to articulate a different common sense in Greece and Spain. In the last election, Ed Miliband spoke of the need to move the ‘centre to the left’. But he failed to articulate this within an effective left-populist discourse. Jeremy Corbyn – aided by an innovative social media campaign – has achieved this. The Labour campaign was based on the articulation of a form of friend-enemy distinction which the political philosopher Ernesto Laclau has argued is essential to all forms of populism. Corbyn claimed to represent ‘the many’ (the people), against ‘the few’ (financial elites, Tories, media barons, et al). This was a rhetoric of mobilisation. And his mobilisation of young people (the turnout figure for 18-24 year olds is estimated to be over 70%) has been one of the big stories of this election.

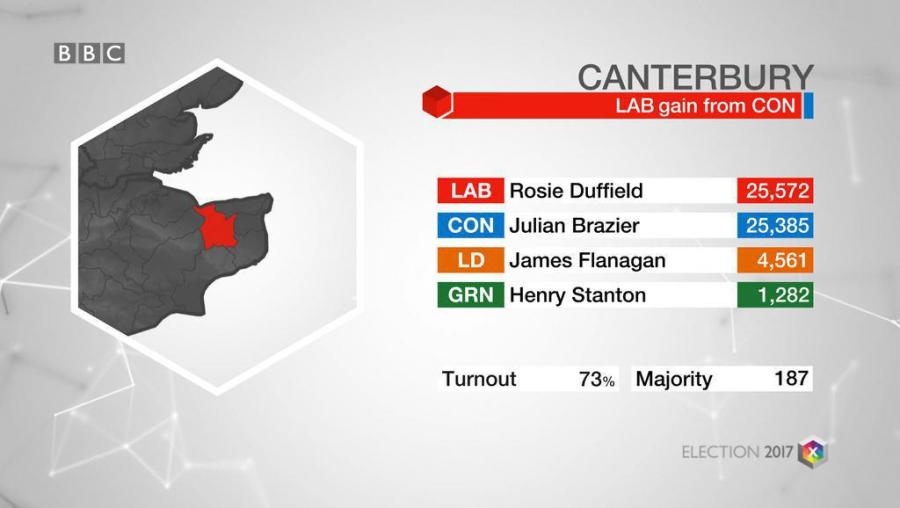

In the Canterbury and Whitstable constituency, it is clear that the mobilisation of young people was a key factor. Another factor has undoubtedly been the palpable lack of popularity of the long-serving MP Sir Julian Brazier. Throughout the campaign, social media has focused on how his free market and socially conservative beliefs have conflicted with the economic interests and beliefs of his constituents. Indeed Sir Julian was considered by many to have taken the electorate for granted. All his opponents were able to capitalise on this, but Rosie Duffield for Labour won through with the votes. It is difficult to imagine someone further away ideologically from Sir Julian (a man who has held his seat since 1987) than the new Labour MP for Canterbury and Whitstable.

As Bob Dylan would no doubt put it: ‘The Times They Are A Changin!’

Politics

Politics Anna Vanaga

Anna Vanaga 668

668