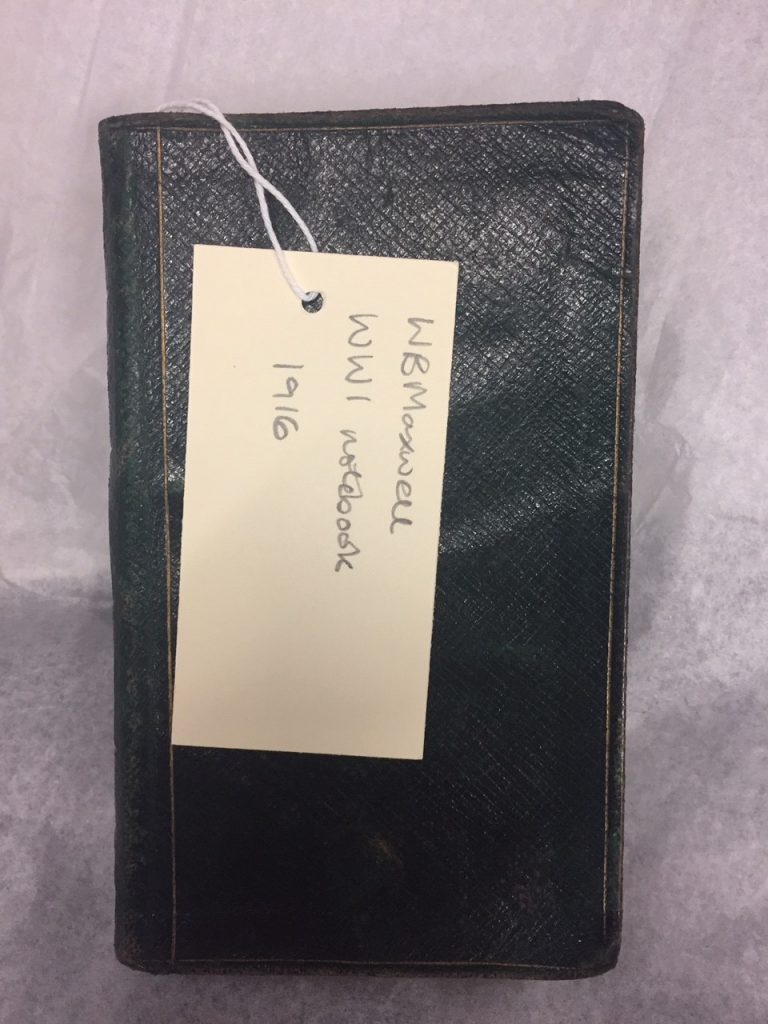

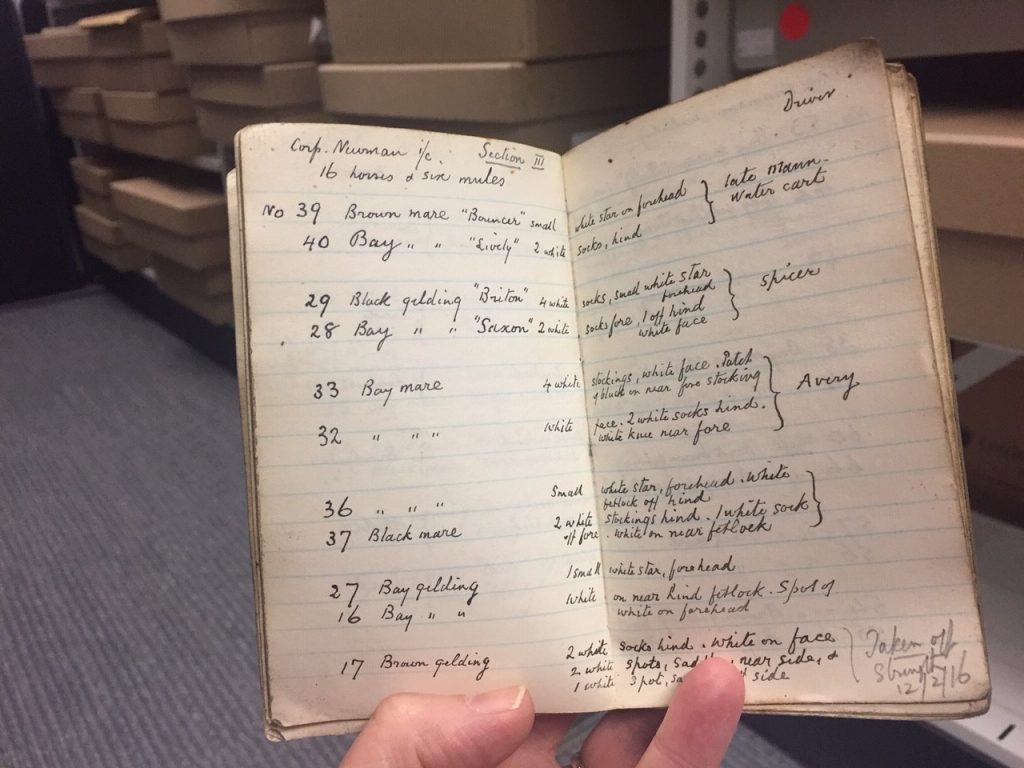

A notebook belonging to W.B. Maxwell, playwright and novelist, details his time serving in France with the Royal Fusiliers in 1916. As the Regimental Transport Officer, Maxwell lists the names of horses and their riders, as well as information about feed, harnessing and care of the horses. This extraordinary little notebook is part of a collection of Maxwell’s diaries, letters and manuscripts held at Augustine House Library.

William Babington Maxwell (1866–1938) was born in London, the son of John Maxwell and Mary Elizabeth Braddon. He grew up in a family that loved riding and described it as introducing “a cheerful element to life” (Maxwell, 1937, p.40). His first pony was “a round-barrelled mouse-coloured friendly creature” called Daisy whom he rode around Richmond Green accompanied by his riding instructor Knight (Maxwell, 1937, p.40). His mother was a keen although somewhat absentminded rider who hunted twice a week during the Spring. In his autobiography, he writes: “She had a truly magnificent grey mare called Vixen and a stockier, less interesting brown mare called Peggy” (Maxwell, 1937, p.141). Maxwell felt a wave of anxiety every time his mother rode out as both rider and horse seemed to never tire. He describes Vixen as “the one perfect horse that, as it proverbially alleged, comes to each of us in a lifetime” (Maxwell, 1937, p.141).

When war broke out Maxwell felt instinctively that he should be doing something, but his lack of military training meant that he wasn’t entirely sure what. He rushed off to his tailors to order a uniform imagining that he might make a “gallant and dashing” (Maxwell, 1937, p.216) aide-de-camp based on reading the stories of Charles Lever. When his tailor asked him his rank, he didn’t know, so he came away with a pocketful of badges, stars and crowns just in case.

Maxwell then purchased riding boots from Peel’s of Oxford Street and a saddle from Champion and Wilton, but when asked whether he wanted a regimental officer’s saddle or a Staff saddle, he wasn’t sure, so he sensibly asked for the most comfortable one.

Kitted out, Maxwell now sought some useful employment within the military but knew that as a 50-year-old man, he would struggle to be accepted into a fighting unit. He was initially given a role as a recruitment officer and later Regimental Transport Officer for a battalion of men from the city of London.

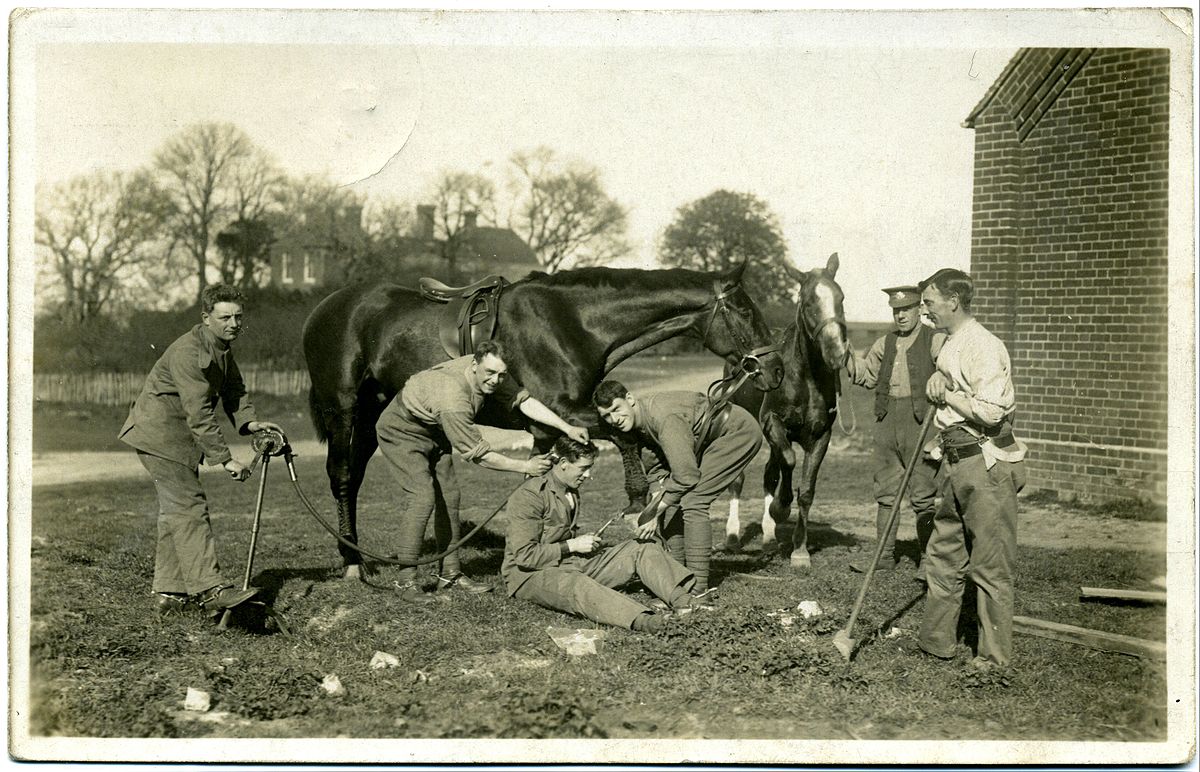

Responsible for 50 or 60 men, of whom only two had any experience of horses, it was Maxwell’s job to teach them how to look after them. Flynn (2012) explains that the mechanisation of public transport in the cities had resulted in a dearth of men who could actually handle a horse. Maxwell writes in his autobiography: “The fact that we had no horses available made riding lessons difficult to organise. I, therefore, bought some more horses again, trusting to the Government or the Lyon Fund to defray the cost in the end“ (Maxwell, 1937, p.223).

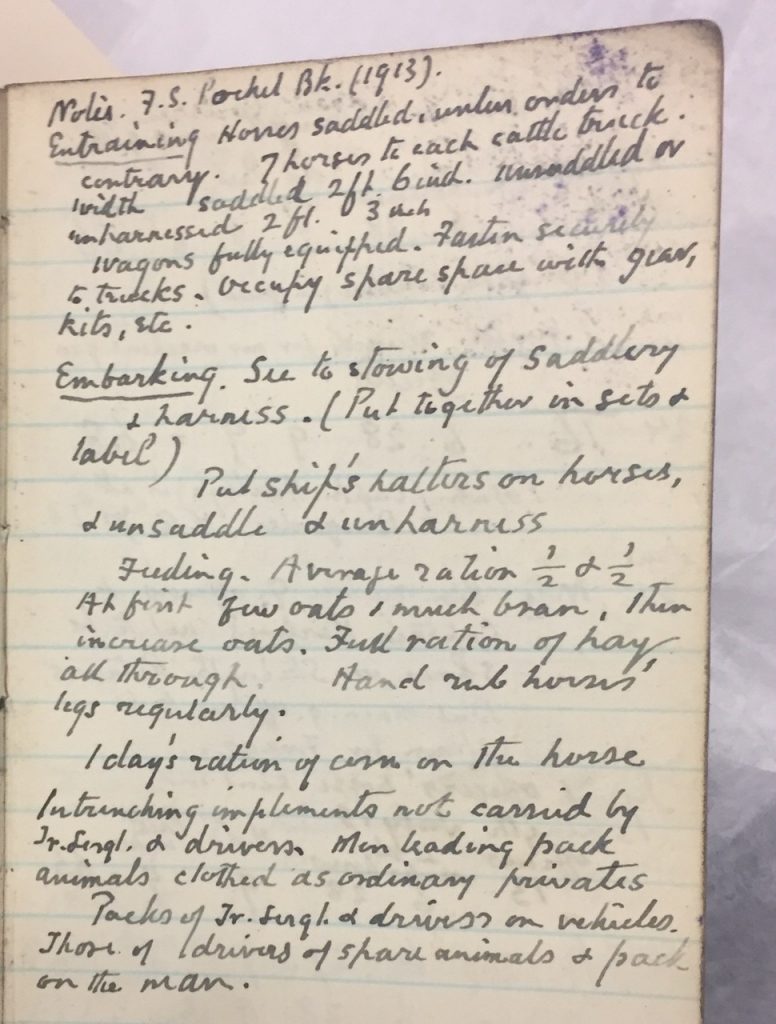

Even with the horses, Maxwell found that the work was difficult, and the men became dispirited, he writes: “I laboured intermittently with my section, teaching them all I could, but, unluckily teaching them a good deal that was altogether useless. We had been given mules and horses but no wagons.” (Maxwell, 1937, p.226). Eventually, Maxwell discovered, after receiving word from France, that limbered wagons were being used and his efforts to teach long rein work had been wasted. Maxwell continued to write in his spare time and contributed to The Times’ Red Cross story book (1915) by famous novelists serving in the armed forces. In 1915, the regiment received orders for France; Maxwell’s notebook outlines the tasks that were undertaken for transporting the horses:

- see to stowing of saddlery and harness (put together in sets and label).

- put ship’s halters on horses and unsaddle and unharness.

- feeding. Average ration ½ and ½ . At first few oats, much bran, then increase oats. Full ration of hay all through.

- hand rub horses’ legs regularly.

On arrival in France, the regiment camped in the dug outs and cellars of Souastre. Maxwell describes the apple orchards and the omelettes and the German shells which “droned high and lazy in the bright warm air” (Maxwell, 1937, p.228). Delays in further orders meant that the mules were harnessed, then unharnessed as the men watched and waited. Eventually, they stood down, to learn later that the Battle of Loos had taken place without them.

In the Spring of 1916, Maxwell was given command of the Divisional Band. He had little knowledge of brass music but was given the task of ordering sheet music from London and devising a weekly programme. As part of his responsibility, he was assigned a wagon, driver and horses who transported the instruments and he had to make sure that the instruments were kept in good repair.

At the Battle of the Somme, Maxwell was instructed with his men, to lead mules carrying bombs to the trenches. He says: “I felt a glow of pride as I thought of the early days at Colchester when the men as such innocents first came to me and the mules were fiery untamed beasts that had to be taught everything also. What a long journey we had made since then” (Maxwell, 1937, p.236).

As the battle progressed, Maxwell witnessed scenes of horror, dead horses and wagons on fire. He writes: “the warm July sun shone down upon death. Men were dying in the bright sunshine – easier at least than to die in cold and darkness” (Maxwell, 1937, p. 236). By 1917 he was sent home as it was feared that he would not cope with another winter.

Maxwell returned to writing novels and plays after the war. In his novel Life can never be the same (1919) set in the fictitious French village of Sainte Chose, the “village street was alive with British soldiers in khaki, horses and mules going to and returning from water, laden wagons passing, companies falling in for parade, sentries on guard, with military police at each end of it to keep order, regulate traffic, and look at people’s passes” (Maxwell, 1919, p.2). It was probably inspired by his time at Souastre.

For anyone interested in the use of animals in warfare, this notebook provides a useful insight into the lives of the horses in Maxwell’s care. If you would like to visit the archives, please email the library to book an appointment.

If you are interested in volunteering and uncovering more stories like these, please sign up at the university’s volunteering portal

References

Flynn, J. (2012) ‘Sense and sentimentality: a critical study of the influence of myth in portrayals of the soldier and horse during World War One’, Critical Perspectives on Animals in Society Conference Proceedings. University of Exeter, UK, 10 March 2012, pp.25-30.

Maxwell, W.B. (1919) Life can never be the same. Indianapolis, The Bobbs-Merrill Company.

Maxwell, W.B. (1937) Time Gathered. London: Hutchinson and Co.

Postcard photo of soldiers and horses during World War I. The postcard is postmarked 1915. The photographer was Fred C. Palmer of Tower Studio, Herne Bay, Kent. Wikimedia Commons.

Library

Library Michelle Crowther

Michelle Crowther 2387

2387