A manuscript of ‘The Strange Adventures of Captain Dangerous’ written by the Victorian author George Augustus Sala has been discovered in the Mary E. Braddon Archive at CCCU. Read on to find out more about this extraordinary find.

“I do not know whether the “Adventures” I have ascribed to Captain Dangerous will be readily recognised as “strange.” To some they may appear exaggerated and distorted, to others merely strained and dull. If truth, however, be stranger than fiction, I may plead something in abatement; for although I am responsible for the thread of the story and the conduct of the narrative, there is not one Fact set down as having marked the career of the Captain that has been drawn from imagination.” – George Augustus Sala

The story is serialized

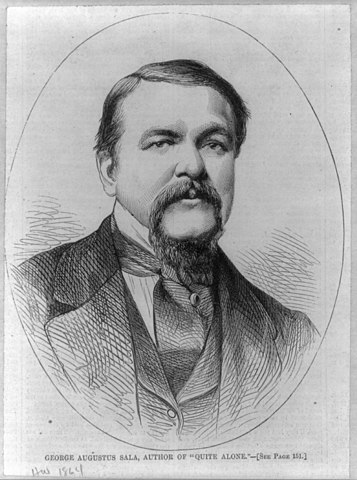

‘The Strange Adventures of Captain Dangerous’ written by the author and journalist George Augustus Sala (1828 – 1895), was serialised in twenty-six chapters in Temple Bar: a London Magazine for town and country readers from January 1862 until February 1863. It is indeed a strange story as the subtitle reveals:

The Strange Adventures of Captain Dangerous: who was a soldier, a sailor, a merchant, a spy, a slave among the moors, a bashaw in the service of the Grand Turk, and died at last in his own house in Hanover Square. A narrative told in old-fashioned English. Attempted by George Augustus Sala.

The story which romps through “countless mutations of fortune” (Athenaeum) includes tales of slavery, which Sala describes as ‘abominable’, arguing that it was “then so Familiar and Unquestioned a Thing in all our Colonies, that its innate and Detestable Wickedness was scarcely taken into account in men’s minds.” (p.44) His strength of feeling on the subject and his in-depth treatment of it in the story may be linked to his own mixed-ethnicity. His great grandmother, Dorothy Thomas, was a former slave.

A reviewer in the Athenaeum magazine described the story as having no plot whatsoever and said that “readers who begin at the last chapter of the third volume and work backwards, will slide into the story just as smoothly at those who in orthodox fashion begin at the beginning.”

A monthly shilling magazine

Temple Bar was a monthly shilling magazine established in December 1860 and published by John Maxwell. It was a rival to the Cornhill Magazine, published by W.M.Thackeray, and although its aim was to capture a respectable middle-class market, it became increasingly sensational.

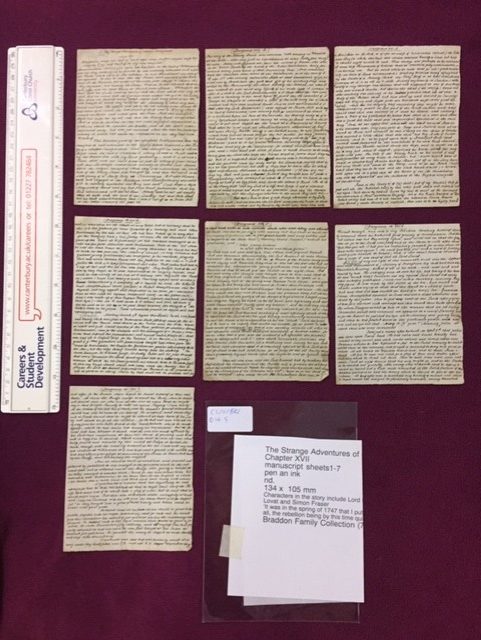

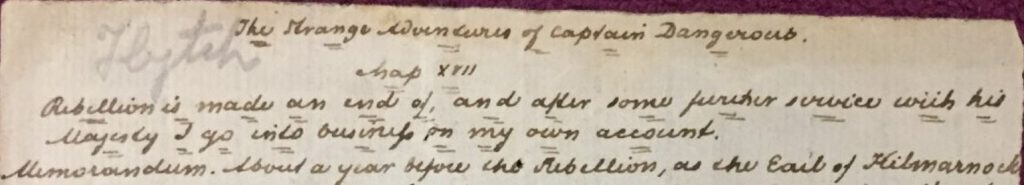

Sala was the first editor of the magazine from 1860-1862 and received £2 a page for his contributions (Blake, 2013). The manuscript below is the first part of chapter 17 of ‘The Strange Adventures of Captain Dangerous’ which was published in October 1862. It is a tiny document with each page 134 mm x 105 mm. (What is extraordinary is that Sala suffered vision loss in one eye, yet was capable of producing such incredibly small and neat writing.) The typeset version which appears in the magazine is 25 pages (You can read it via British Periodicals) so presumably, Sala was paid £50 for this chapter. These seven pages only represent the first seven pages of the chapter. They have been annotated with the names of the printer compositors who were responsible for setting the type blocks and producing the finished article. These have been added in pencil throughout the document and reveal how the document was divided up and worked on.

The Manuscript

The name Flytch or Hytch has been pencilled on the top of the first page of the manuscript in another hand. It is possible that this was Joseph Hytch (1819-1884), a printer’s compositor who lived in Upper Park Street, Islington, and whose name is variously spelt as Flytch, Hytch and Hytche. The double underlines are the textual marks that indicate where the compositor should use capital letters. Here they are used to indicate the title and subtitle of the piece.

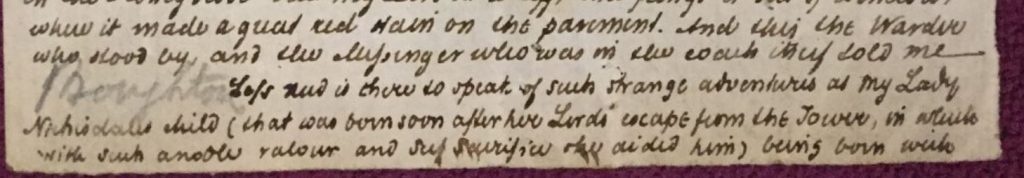

On page two near the bottom of the page, a new name is added to the manuscript – Boughton. This is possibly Henry Boughton (1834-), a lithographic printer living in Holborn. There are no images within the completed story as it was considered too expensive to insert them, so Henry may have been doubling up as a compositor at this time or it is another member of his family who is working as a compositor.

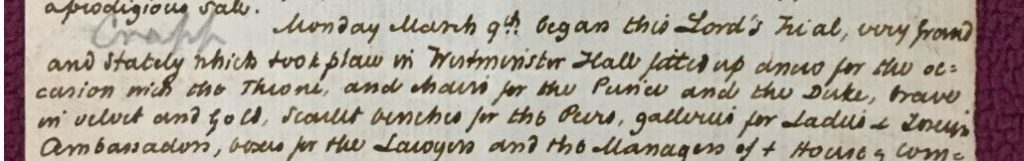

On page 4 we see the name Crapp. John Crapp (1834- ) was a compositor living in South Hackney.

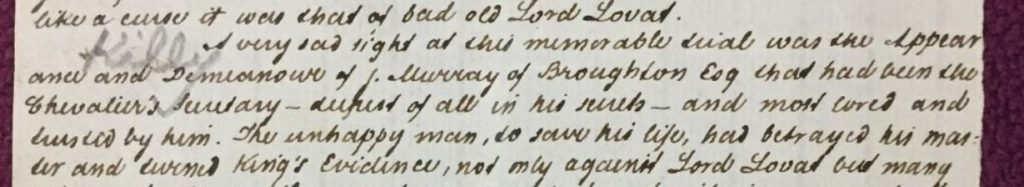

On page 6 the name Killy appears (although census evidence suggests that this name was actually Kelly). This could be Samuel Rosser Kelly (1801-), Arthur Bower Kelly (1838-) or Samuel Bower Kelly. (1836- ). Samuel R. Kelly was a letter press printer and his sons Arthur and Sam were printer’s apprentices. The family were living in Bow, Poplar.

These men who were responsible for ensuring the accuracy of the printed document have ironically suffered the fate of the census enumerator or genealogist in the recording of their own names. What we can learn from the censuses is the age of these men and where they lived. It gives us an insight into their lives and the economic status of the printer compositor. Temple Bar was printed by William Clowes and Son, Stamford Street and Charing Cross from at least 1869 however earlier copies do not include printing information. Although earlier in the century, Clowes had been criticised for poor wages, by the 1860s, it supported almshouses for printers and had a rowing club, so conditions seem to have improved.

Connections with Mary Elizabeth Braddon

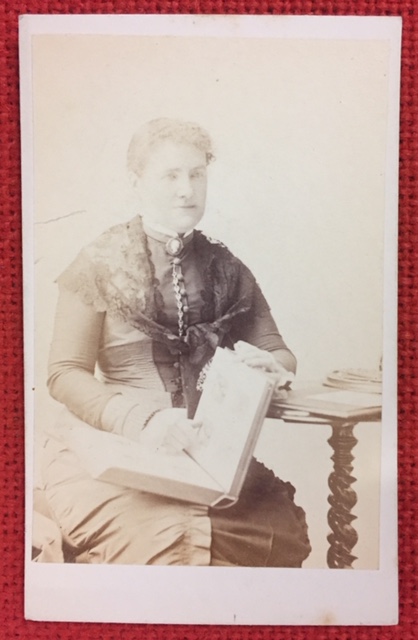

Chapter 29 of “Aurora Floyd”, a serialised story by Miss Braddon was in the same October issue of Temple Bar as ‘The Strange Adventures of Captain Dangerous’. Mary Elizabeth Braddon was living with the publisher John Maxwell at this time and she was later to become his wife. She also edited Temple Bar and this may help explain why the manuscript was tucked in with Braddon’s manuscripts and letters. Sala had known Braddon for some time and knew both her and her mother.

We do not know how the editor, the publisher and Miss Braddon got on at this time, however, we do know that in the preceding year Maxwell was not entirely happy with Sala’s editorship and the direction he had been taking the magazine. In August 1861, Maxwell wrote to Anthony Trollope asking if he would write a novel for Temple Bar “and fill the position that Mr Sala now occupies” (De Baun, ‘The Story of Temple Bar’, 44, quoted in Blake, 2013) He offered him £1000 per annum for three to five years (Blake, 2013).

Trollope did not accept and so Maxwell and Sala continued to work together. It is possible that Maxwell had been unhappy with Sala’s rejection of Braddon’s manuscript ‘About the Childhood of Tommy and Harry & Introduction ‘to the Reader’ – the History of a Bad and a Good Boy which she had sent Sala weeks earlier (Letter to Sala, 14 July 1861). It was not published in Temple Bar and Sala wrote hastily to Maxwell from the Reform Club saying “Tommy and Harry with Miss Aurora no” The no is underlined six times to emphasise his feelings. He describes it as the “old pig-tail and square-toed business all over again.” (Letter to Maxwell, undated) Instead, he promises to write the concluding portion to “Dangerous”.

By 1862 Temple Bar was “not making a mint of money” (Sala, 1895, p.3) but Maxwell was reluctant to sell the copyright of the magazine. Sala resigned his editorship at Temple Bar in October 1863, eight months after he completed “The Strange Adventures.” He was to set off on his own adventures as a reporter on the American Civil War for the Daily Telegraph (Blake, 2013). According to his autobiography, he had earned about £2,000 in 1863 but constant criticisms from reviewers left him feeling discouraged. He decided to abandon literature for journalism (Sala, 1895, p.364) The Strange Adventures of Captain Dangerous was quickly published as a novel and in 1864 Sala’s Breakfast in Bed was published by Maxwell as a cheap 2 shilling edition.

A continuing friendship?

A letter at the Harry Ransome Center, University of Texas reveals that Sala and Mary Braddon corresponded in 1892, three years before his death, so presumably, there were no hard feelings about the rejected manuscript. However, his death is not recorded in her diary.

After his death in 1895, Sala was described in the Tablet as having “humour, a dash of cynicism, and a perfect armoury of anecdotes; all of which coupled with his easy gossipy style, helped to place him at the head of descriptive writers.”

Works Cited

Blake, P. (2010) “The Paradox of a Periodical: Temple Bar Magazine under the Editorship of George Augustus Sala (1860–1863),” The London Journal 35 (2): pp.185-209.

Braddon, M.E. ‘About the Childhood of Tommy & Harry’ & Introduction ‘to the Reader’ – the History of a Bad and a Good Boy. Letter Addressed to: George Augustus SALA Esq., 14 Clements Inn, London E. C. July 14 1861. Braddon Archive, CCCU.

Sala, G.A. “The Strange Adventures of Captain Dangerous; Who was a Soldier, a Sailor, a Merchant, a Spy, a Slave among the Moors, a Bashaw in the Service of the Grand Turk, and Died at Last in His Own House in Hanover Square; a Narrative in Old-Fashioned English.” Temple Bar. (1862-3) ProQuest. Web. 8 Nov. 2021.

Sala, G.A. Letter to Maxwell. Undated. MSS_WolffRL_37_20_008

Sala, G.A. (1895) The life and adventures of George Augustus Sala, written by himself. New York : C. Scribner’s Sons.

“The Late George Augustus Sala” Tablet. Saturday 14 December 1895.

“The Strange Adventures of Captain Dangerous; who was a Soldier, a Sailor, a Merchant, a Spy, a Slave among the Moors, a Bashaw in the Service of the Grand Turk, and died at last in his own House in Hanover Square; a Narrative in Old-fashioned English. 1863,” The Athenaeum, (1852), pp. 546-547.

Image Credits:

George Augustus Sala, 1895, Allister, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

George Augustus Sala, bust portrait, facing right LCCN2005686039. Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

M.E. Braddon, Photograph from the M.E. Braddon Collection, International Centre for Victorian Women Writers, Canterbury Christ Church University.

Images of the manuscript are taken from the original in the M.E. Braddon Collection, International Centre for Victorian Women Writers, Canterbury Christ Church University.

Library

Library Michelle Crowther

Michelle Crowther 1970

1970