Introduction

This year’s theme for LGBTQ+ History month is science and innovation. This blog post explores the life of Elke Mackenzie, a British botanist who devoted much of her career to the study of lichens, nature’s quiet, often overlooked organisms, a story similar to Mackenzie’s own academic presence within lichenology.

Much of Mackenzie’s research was published under her former name, which is not repeated here due to Mackenzie’s later gender transition and inability to consent to its continued use. Due to this, both her work and her gender identity have been frequently overlooked within scientific literature. This post aims to shed light on Mackenzie’s life and her devotion to lichens, and to show why her voice and research continues to matter.

Who is Elke Mackenzie?

Elke Mackenzie was born on 11 September, 1911, in Clapham, London. Her interest in botany, however, developed in Edinburgh, where she moved as a child with her family. After graduating from Edinburgh Academy in 1929, she went on to study Botany at the University of Edinburgh, graduating in 1933 with a Bachelor of Science.

It was here that Mackenzie began her botanical path that would lead her to become such an important figure in twentieth-century lichenology.

The image above is a photo by Jorge Franganillo. Sourced by Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0 Attribution 2.0 Generic, Deed – Attribution 2.0 Generic – Creative Commons, via Wikimedia Commons.

What are lichens?

To understand Mackenzie’s work, it helps to first understand what lichens are. You have likely come across a lichen before, perhaps mistaking it for moss. They appear in many forms: mustard yellow patches mottling tree bark, rosettes spreading across stones and up walls, or wispy, fern-like growths.

‘Sunburst Lichen’ image taken by NickyPe sourced by Pixabay, Content License – Pixabay

‘Lichen on a Wall‘, photo taken by Stephen McKay. Sourced by Wikimedia commons, CC BY-SA 2.0 Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic, Deed – Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic – Creative Commons, via Wikimedia Commons.

Lichens resist simple classification. Although they are classified as fungi, they are not single organisms but a synthesis of two or more. By definition, a lichen is a symbiotic relationship between a fungus and an alga or cyanobacterium, and sometimes both. As Mackenzie herself explained in Scientific American:

“A lichen is not a simple plant, a single unit of plant life, but a duality. Two entirely different organisms—a fungus and an alga—associate to form a lichen.” (1959, p.144)

When you look at a lichen, you are primarily looking at the fungal partner. Essentially, the fungus acts as a structure in which the alga can live, while the alga in turn produces food for the fungus. This reciprocal relationship means lichens can withstand some of the most extreme environmental conditions.

‘Crust Lichen Rock Limestone’, by Hans – Pixabay. Image sourced by Pixabay, Content License – Pixabay

A Brief History of Lichens

Lichens have not always been quite so well understood. Their complex nature meant they did not fit neatly into existing classification systems, making them a source of uncertainty and mystery within the realm of botany. For centuries, then, lichens were simply assumed to be plants.

‘Lichen Usnea Vegetale Beard’ by Camera-man – Pixabay. Image sourced by Pixabay, Content License – Pixabay

‘Lichen on Willow‘, photo taken by by Ed Iglehart. Sourced by Wikimedia commons, CC BY-SA 2.0 Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic, Deed – Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic – Creative Commons, via Wikimedia Commons

It wasn’t until 1867 that the Swiss botanist Simon Schwendener proposed what became known as the dual lichen hypothesis, suggesting that lichens were composed of two separate organisms. This idea was initially rejected by many leading lichenologists of the time and was only widely accepted toward the end of the nineteenth century. As lichenologist Ilse Honegger observed in his 2000 article in The Bryologist, resistance to Schwendener’s theory was not based purely on empirical evidence, but on how life itself was understood at the time. In the nineteenth century, life was viewed mainly through a Darwinian logic, which emphasised individual organisms and antagonistic relationships, leaving little room for concepts such as symbiosis and dual organisms.

It is this developing scientific context that Mackenzie entered, at a time when lichens were beginning to reshape how biologists understood life itself.

Mackenzie’s Early Career

Mackenzie’s interest in lichens developed through her role as an Assistant Keeper in the lichen collections of London’s British Museum in 1935, now known as the Natural History Museum. There, she apprenticed under Annie Lorrain Smith, a renowned lichenologist who carried out her work at a time when women were not formally employed by the museum.

Photo by Grant Ritchie on Unsplash

According to George A. Llano’s obituary for Mackenzie, published in The Bryologist (Autumn 1991), Mackenzie regarded herself as Smith’s disciple. Under Smith’s mentorship, Mackenzie became particularly interested in Antarctic lichens, which at the time were comparatively more unknown than other species of lichens.

In 1936, Mackenzie married Maila Elvira Laabejo, and in 1940 they had their first son during the Blitz in London. Amid the personal and political changes in her life, Mackenzie’s interest in Antarctic lichen flora persisted. In 1943, she received her doctorate from the University of Edinburgh, writing a monographic thesis on the subantarctic genus Placopsis, undertaken in part to improve the identification of specimens held in the British Museum Herbarium.

The image above is by Jason Hollinger. Sourced by Wikimedia commons, CC BY 2.0 Attribution 2.0 Generic, Deed – Attribution 2.0 Generic – Creative Commons, via Wikimedia commons.

Operation Tabarin

Soon after she completed her doctorate in 1943, Mackenzie took a leave of absence from the British Museum to partake in Operation Tabarin, Britain’s secret wartime expedition to the Antarctic Peninsula. The operation aimed to maintain British sovereignty over Antarctic territories and was comprised of a small team of scientists, including Mackenzie.

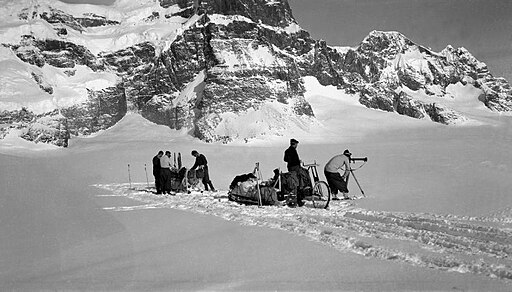

It was this expedition that provided Mackenzie the means to directly collect lichens. There, she undertook a range of roles, from botanist to dog-driver and surveyor’s assistant.

‘Operation Tabarin. Survey field work ‘ by Marr, James, supplied by British Antarctic Survey, image reference BAS:AD6/19/1/A42/7, https://www.bas.ac.uk/about/about-bas/history/operation-tabarin. Sourced by Wikimedia Commons, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Mackenzie learned to adapt her work to the harshness of the Antarctic climate, packing lichen specimens into soft snow inside pemmican boxes to preserve them, and later drying them in sunlight or on stones heated over pressure stoves in their tents.

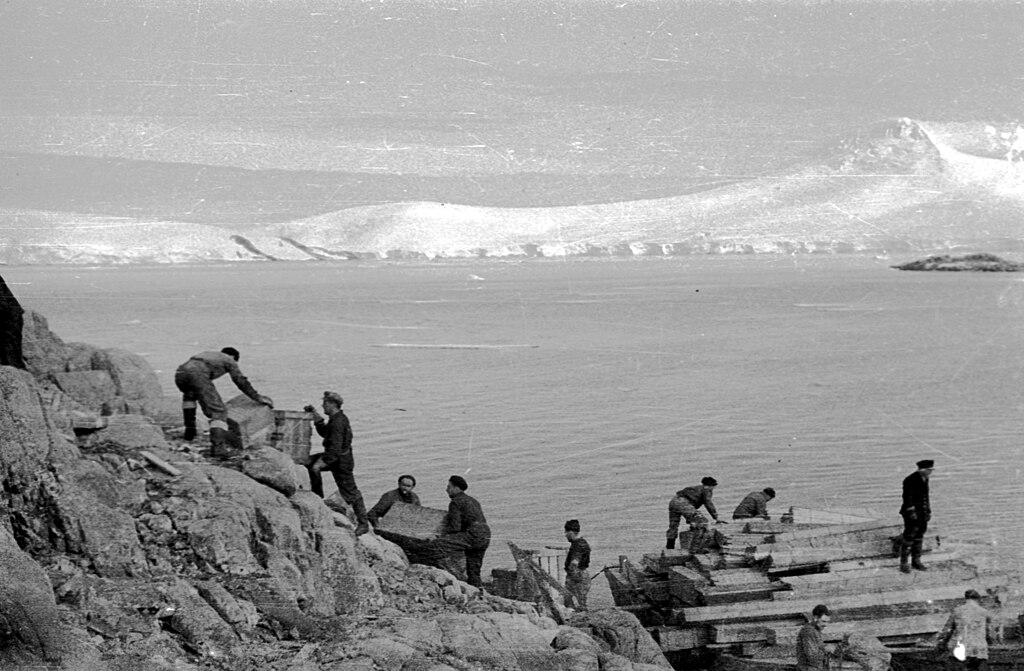

‘British Antarctic Survey 1944’ by Alan William Reece, supplied by British Antarctic Survey, archives reference: AD6/19/1/A1/29, https://www.bas.ac.uk/about/about-bas/history/operation-tabarin. Sourced by Wikimedia Commons, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

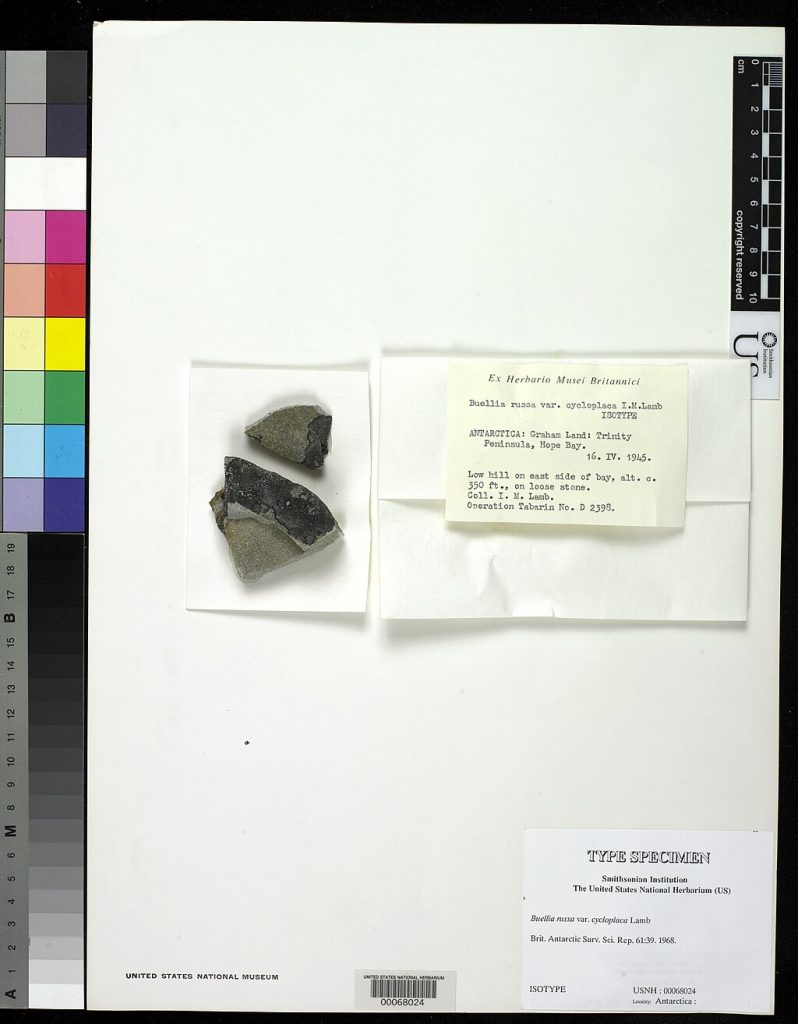

Over the course of the operation, Mackenzie and her team collected more than 1,000 botanical specimens, including 865 lichens, many of which were new to science. One of which includes Verrucaria serpuloides, the only known marine lichen which lives permanently underwater.

‘Buellia russa var. cycloplaca I.M. Lamb’, image by National Museum of Natural History as part of the Smithsonian Institution’s Open Access collection. Sourced by Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0 Universal, Deed – CC0 1.0 Universal – Creative Commons, via Wikimedia Commons.

Alongside her scientific work, Mackenzie kept a typewritten diary that documented both the harshness of Antarctic life and moments of quiet familiarity found through community and nature. She took pleasure in shared dinners of freshly fried rock cod and seal steaks, evenings filled with music, and sunny days spent collecting lichens from the shore. Mackenzie’s diaries offer an invaluable glimpse into the lived experience of scientific fieldwork and Operation Tabarin, an expedition that remains largely unknown due to its secret wartime nature.

‘Operation Tabarin. Base B location’ by Elke Mackenzie (archived under a former name), supplied by British Antarctic Survey Archives Service, image reference BAS:AD6/19/1/B118/2. https://www.bas.ac.uk/about/about-bas/history/operation-tabarin. Sourced by Wikimedia Commons, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The above three images of Operation Tabarin are supplied by British Antarctic Survey Archives Service, with further images available here. These works created by the United Kingdom Government are in the public domain, all sourced via Wikimedia commons.

Mackenzie’s Later Career

Mackenzie’s later career is not as largely recorded as her earlier work, though it remained marked by her passion for botany, and a desire to understand the difficult lichen genus Stereocaulon in its entirety.

In 1947, she took up the role of Professor of Cryptogamic Botany at the University of Tucumán in Argentina, before becoming a curator of cryptogams at the National Museum of Canada in Ottawa in 1950. Cryptogams are plant-like organisms that reproduce through spores rather than seeds, such as algae, mosses, and ferns.

‘Polystichum setiferum’ by Georges Jansoone, JoJan. Sourced by Wikimedia Commons, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

It was in 1953 that Mackenzie accepted what would become her final and most prestigious position as Director of the Farlow Herbarium at Harvard University.

‘Farlow Herbarium – Harvard University – Cambridge’, image taken by Daderot. Sourced by Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0 Universal, Deed – CC0 1.0 Universal – Creative Commons, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Adventures of Elke Mackenzie

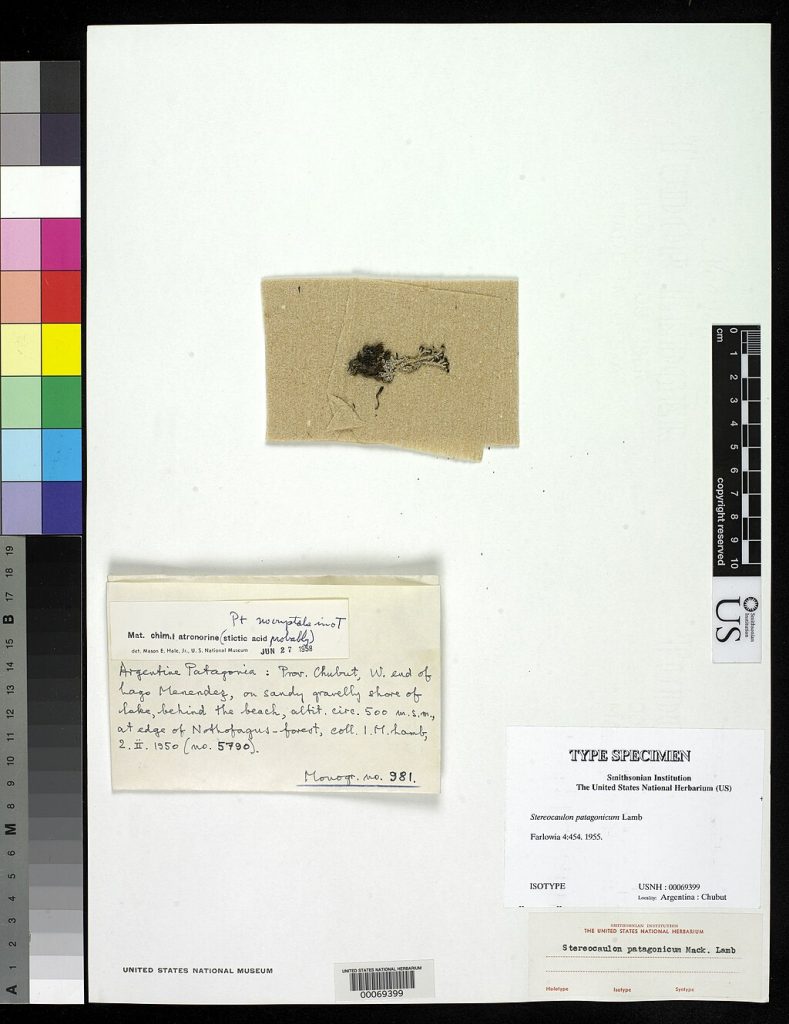

During this period, Mackenzie travelled extensively in pursuit of lichen research. From the mountains of Tucumán and Salta in Argentina, where she furthered her monographic work on Stereocaulon, to the Atlantic coast of Patagonia, supporting the Farlow Herbarium’s collections of marine algae, lichens remained a constant presence in her life.

‘Stereocaulon patagonicum I.M. Lamb’, image by National Museum of Natural History as part of the Smithsonian Institution’s Open Access collection. Sourced by Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0 Universal, Deed – CC0 1.0 Universal – Creative Commons, via Wikimedia Commons.

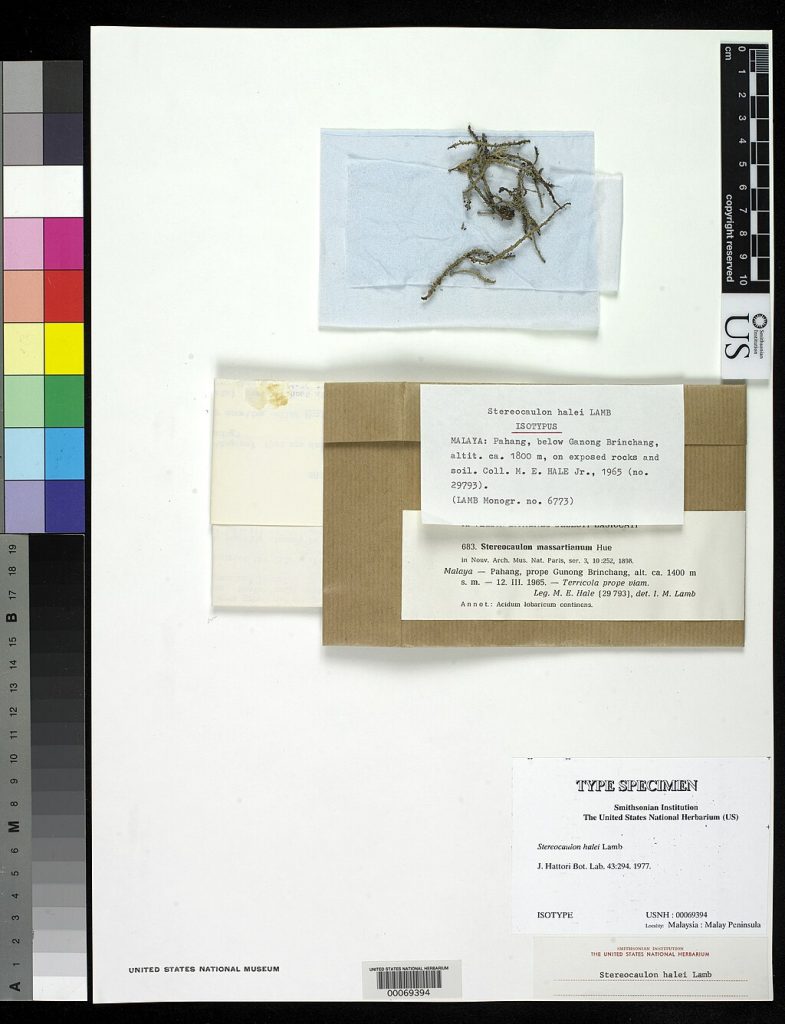

‘Stereocaulon halei I.M. Lamb’, image by National Museum of Natural History as part of the Smithsonian Institution’s Open Access collection. Sourced by Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0 Universal, Deed – CC0 1.0 Universal – Creative Commons, via Wikimedia Commons.

In 1964, she returned to Antarctica once more, naming the expedition ‘Operation Gooseflesh’. A name given in jest of the original operation, and perhaps a wry nod to the prickled skin of diving into freezing Antarctic waters to continue research into the marine algae first encountered during Operation Tabarin. Alongside a small team of researchers, Mackenzie collected approximately 500 specimens of marine algae during this expedition.

Mackenzie’s Lasting Legacy

In the 1960s, Mackenzie began to experience periods of poor mental health. She was initially diagnosed with dysphonia syndrome, a disorder affecting the voice box and what would now be understood as gender dysphoria. It was in 1971 that Mackenzie transitioned from male to female and adopted her name Elke. She retired from her role as Director of the Farlow Herbarium in 1972 and moved to Costa Rica, where her focus gradually shifted away from botanical research to translating botanical German textbooks into English.

‘Costa Rica Monteverde’ by JanBartel. Image sourced by Pixabay, Content License – Pixabay

After later returning to Cambridge in England, Mackenzie was diagnosed in 1983 with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a neurodegenerative disease affecting the nerve cells of the brain and spinal cord. Mackenzie died in 1990, at the age of seventy-eight.

Elke Mackenzie… a Hitherto Overlooked Lichenologist

Today, much of Mackenzie’s scientific work is overwritten by her former name. Her academic research, type-written diaries from Antarctica, and very existence as a lichenologist within botanical archives and collections, are all credited to an identity that Mackenzie no longer aligned with. Even within scientific papers and obituaries, Mackenzie is repeatedly misgendered.

It was in one of her final works published in 1972, “Stereocaulon arenarium… a hitherto overlooked boreal-arctic lichen”, that Mackenzie quietly asserted her identity by citing herself in a footnote, with a thanks to:

“Miss Elke Mackenzie for technical and bibliographic assistance in the preparation of this paper.” (p.10)

A small act, but one in which Mackenzie refused to be silenced and have her work divorced entirely from who she was.

The image above is by Syrio. Sourced by Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0 Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International, Deed – Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International – Creative Commons, via Wikimedia Commons.

Whilst Mackenzie never completed her monograph on Stereocaulon due to a series of unfortunate circumstances, her work on the genus proved invaluable in addressing significant gaps in lichen research, with many of her ideas and hypotheses continuing to hold up in light of our modern biological insights.

Present Day Lichenology

Today, lichens are recognised as valuable environmental health indicators. As Prado notes in their 2025 article in The Journal of Fungi, lichens can accumulate trace elements and metals from the air and soil, making them useful bioindicators of atmospheric pollution. They are also sensitive to climatic conditions, meaning their presence or waning absence can reveal subtle changes in climate.

‘Lichen Tree Forest Nature’, by JerzyGórecki. Image sourced by Pixabay, Content License – Pixabay

Prado also notes that recent research has also highlighted lichens potential within medicine, with studies exploring the unique chemical compounds found in Antarctic lichens and their possible applications in treating neurodegenerative and cancer-related diseases. That this research continues is especially poignant given that Mackenzie herself suffered from neurodegenerative disease, ALS.

Conclusion

Writing in her 1959 article in Scientific American, Mackenzie noted that “lichens do not fossilize readily” (p.144) due to their softer forms, meaning they are often absent from geological records. Like Mackenzie herself, lichens are easily overlooked by the systems that record and preserve history. Recognising figures like Elke Mackenzie during LGBTQ+ History Month allows us to see how LGBTQ+ individuals have discreetly shaped scientific knowledge, even when they have not always been acknowledged.

Lichens have been integral in modern biological thought, with their existence challenging scientific assumptions by revealing life not as singular or fixed, but as collaborative and interdependent. As biologists Scott F. Gilbert, Jan Sapp, and philosopher Alfred Tauber note in their 2012 article in The Quarterly Review of Biology, symbiosis has become a central tenet of modern biology:

“For animals, as well as plants, there have never been individuals. This new paradigm for biology asks new questions and seeks new relationships among the different living entities on Earth. We are all lichens.” (p.336)

The next time you notice a lichen on a wall, the bark of a tree, or hiding under a stone, it may be worth pausing to look a little closer. In these small, resilient organism lies a story of cooperation, symbiosis, and quiet transformation, one that Mackenzie devoted her career to understanding and refused to separate from her own story as a woman.

‘Terrestrial vegetation of Antarctica’ by T.Voekler. Sourced by Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0, Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported, Deed – Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported – Creative Commons, via Wikimedia Commons.

Bibliography

Featured Image: ‘Cup Lichen Trumpet Moss’, by YAKY_X. Image sourced by Pixabay, Content License – Pixabay

- Gilbert, S. F., Sapp, J., Tauber, A. I., Handling Editor James D. Thomson, & Associate Editor Stephen C. Stearns. (2012). A Symbiotic View of Life: We Have Never Been Individuals. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 87(4), pp.325–341. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1086/668166

- Honegger, R. (2000). Simon Schwendener (1829-1919) and the Dual Hypothesis of Lichens. The Bryologist, 103(2), pp.307–313. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3244159

- Imbler, S. (2020) The Unsung Heroine of Lichenology. JSTOR Daily. Available at: https://daily.jstor.org/the-unsung-heroine-of-lichenology/

- Johnston, E. (2022). Lichen Adventurer: Elke Mackenzie. Royal Botanic Gardens Kew. Available at: https://www.kew.org/read-and-watch/elke-mackenzie

- Lamb, I. M. (1959). LICHENS. Scientific American, 201(4), pp.144–159. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24940423

- Lamb, I. M. (1972). STEREOCAULON ARENARIUM (SAV.) M. LAMB, A HITHERTO OVERLOOKED BOREAL-ARCTIC LICHEN. Occasional Papers of the Farlow Herbarium of Cryptogamic Botany, 2, pp.1–11. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41760390

- Llano, G. A. (1991). I. Mackenzie Lamb, D.Sc. (Elke Mackenzie) (1911-1990). The Bryologist, 94(3), pp.315–320. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3243974

- Prado, T., Sylvian Degrave, W.M, Duarte, G.F. (2025). Lichens and Health—Trends and Perspectives for the Study of Biodiversity in the Antarctic Ecosystem, Journal of Fungi, 11(3), p. 198. Available at: doi:10.3390/jof11030198.

- Schneider, A. (1895). The Biological Status of Lichens. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club, 22(5), pp.189–198. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/2478161

- The British Lichen Society (no date). What is a Lichen? Available at: https://britishlichensociety.org.uk/learning/what-is-a-lichen

- The University of Edinburgh (2024). Elke Mackenzie (1911-1990). Available at: https://alumni.ed.ac.uk/services/notable-alumni/alumni-in-history/elke-mackenzie

Library

Library Amelia Turner

Amelia Turner 331

331