Revd Dr Ivan Khovacs, Senior Lecturer in Theology and Religion, Philosophy & Ethics, reflects on the Level 6 module ‘Religion and the Environment‘ within the BA (Hons) Theology

“When was the last time you peeled a potato?” It’s an unusual question to start a module with, but it was a way to get students in Religion and Environmental Ethics to think about their role in sustainability and care of the environment. Food was a way of making the environmental ethics something students could relate to. Yes, we are living an environmental crisis; but to speak of human responsibility for ‘climate change’, ‘the planet’, and ‘future generations’ is to speak in abstractions. Even the detrimental impact humans have had on landscapes, waterways, plants and animal life, or the projected population shifts the world will experience in coming years from mass migration due to climate change, is not sufficiently concrete. Our Theology and Religion, Philosophy and Ethics students needed some personal and communal account of why they should care: we needed a narrative of human values and of sources of hope that could lead from ethical analysis to action and change.

Never mind that one student had never peeled a potato, and another didn’t believe that potatoes should ever come as anything other than chips, hot and steamy from the burger van outside Verena Holmes! You are what you eat, someone said. Inevitably, the choices we make about the food we eat raises questions of human value. What we give up, and what we take on as concrete commitments to the environment, is ultimately a question of meaning: what does it mean to be human if not to act for the good of others and for the good of the planet?

At the same time, if in our consumerist age we have lost connection with nature and lost sight of our complete dependence on what the earth provides, we need to look no further than the food on our table. The food we eat—where it comes from, how it reaches us, how it’s grown, what counts as food and what doesn’t—all of it has an impact on the natural world. This, then, was the questions for our module: could food become a site for philosophical reflection, could tastebuds be knowledge nodes connecting us to the soils and oceans where our food comes from and to an ethics of care? It’s a big question. But the students were up for it, frightfully cheerful, even, to dig in!

That said, students were deeply challenged to learn, for example, that our collective appetite in the West for ‘superfoods’ like avocadoes, goji berries, quinoa, and chia seeds—with profit margins driving intensive irrigation and outsized production scales—are depleting the soils where these foods are grown. Then again, when the food we eat is grown half a world away on lands we have no connection to, what does it look like to really care? But food also has a way of making the global local and the abstract personal.

The local for us included the soil beneath our feet, in fact, the very land on which our campus sits. In one session students got to sip real ale (courtesy of Peter Rands) brewed from hops that connect our campus to its land history: a Benedictine abbey where apple, pear, and hazelnut orchards nourished a religious community and its surrounding populations. Part of our campus was once an ancient hop garden supplying the dry, bitter-sweet flowers that give us the modern English ale.

On another occasion, students tasted apple juice pressed from apples grown in Canterbury—“You can actually taste the apples in it!” one student remarked, putting into words our collective experience of natural goodness. That explosion of taste was nothing less than time-travel connecting us to those ancient monastic orchards, to a time when people ate what they could grow. Of course what they grew was also what they prayed for: “give us today our daily bread.” Our campus, it turns out, is a daily walk in sustainability heritage: scratch the surface and you quickly find a rich and deeply embedded agricultural and spiritual life.

Further into the term, we turned our attention to local production and seasonal foods to explore an ethics of gratitude, compassion, and community-building sustained by efforts in organic farming. From Maria Diemling, we learned about Jewish teaching about the relationship between land, the body, and the holy. We also read the work of farmers inviting us to recover an ‘agrarian spirit’, to tether our working lives and wellbeing to nature’s rhythms and seasons.

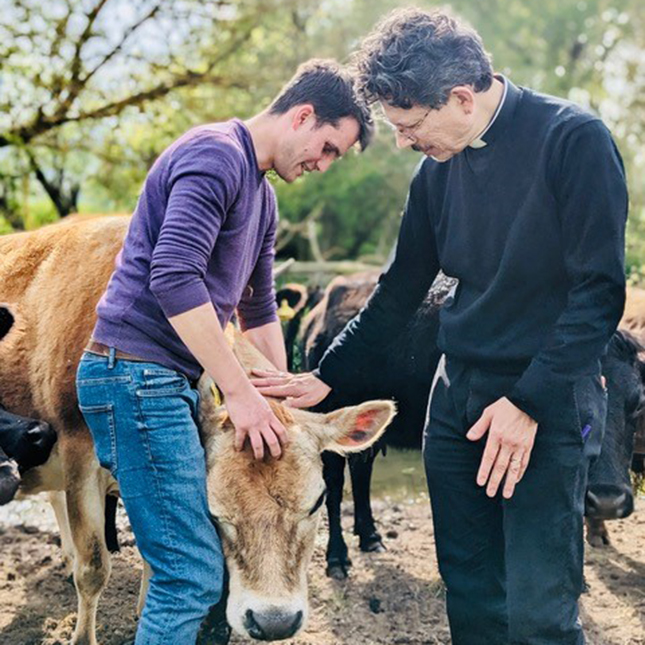

For most of us, even in a place we call the Garden of England, soils and substrates where biological and chemical processes sustain microbiology, or the waterways that vein our landscapes above and below ground, are hardly a daily concern. But things look different when you speak to people who believe that food grown locally and lovingly is the key to putting humanity and community back at the centre of food production, distribution, and enjoyment. So, we finished the semester with a visit to Oink & Udder, an organic farm started by our Theology graduate David Wilcock.

David says it was his wife Chloe who first had the idea to turn from her Music and Teaching degree to farming goats, cattle, and pigs. They also invited us to meet their organic crop farmer neighbour from Nonington Farms. From them, we learned about the science of food, how crops and animals turn grasses into protein, and how the symbiosis of plant and animal cycles pack carbon safely into the ground. They also spoke about how good food can build community life and networks of wellbeing beyond food banks. Together, these neighbours to Canterbury Christ Church are redefining animal welfare, love of land, and the link between community to wellbeing. We even learned that what our grandparents used to tell us was true all along: if you peel the potato, you peel away the goodness.

Clearly, though, a well-scrubbed potato could only have goodness if there was good, healthy, unpolluted soil to begin with, and if water was plentiful because the seasons were favourable; if human hands dug into the dirt to pick the tuber, and a chain of human labour was responsible for loading produce and bringing it to market. And although we are removed from the soils, climates, and processes responsible for a potato freshly pulled from the ground, it is in the end a goodness we can touch, see, smell, savour, and share. And now it is a goodness which our students, looking at that jacket and potato on their dinner plate, could decode as a story of ethics, sustainability, the environment, and all the reasons why we should care.

*************************************************************************************************

Follow the Canterbury Christ Church University Theology team on Instagram

Find out more about studying Theology at Canterbury Christ University HERE Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Education

Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Education Caroline Holden

Caroline Holden 621

621