Thahmina Begum Thaniya reviews Zoulfa Katouh’s debut novel and reflects on how literature can offer insights that strengthen our political analysis.

On December 28 2024, the Gardenia Choir performed the poignant lyrics of one of Abdelbaset al-Sarout’s revolutionary anthems, “Oh Mother, I Come to You as a Martyr,” within the walls of Bayt Fahri, a site now situated in a liberated Damascus. The tears visible on the faces of the choir members symbolised the culmination of a long and arduous struggle and served as a reminder that Syrians never forget their martyrs. Sarout’s words, emblematic of the Syrian resistance over the past thirteen years, reverberated through a city that had long borne the scars of war, encapsulating both the enduring strength and the profound losses experienced by the Syrian people.

In the wake of the continued release of harrowing images from Syria’s torture chambers and the desperate searches by families for missing loved ones across various online platforms, the full extent of Bashar al-Assad’s repressive regime has become undeniable. What Syrians have tirelessly endeavoured to expose over the past years is now unmistakably evident. More than a month after the fall of Damascus to the rebel group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham and the subsequent collapse of Assad’s regime, Syrians both domestically and abroad are still celebrating the demise of a dictator who ruled for 24 years, signalling the end of over five decades of Assad family control in Syria.

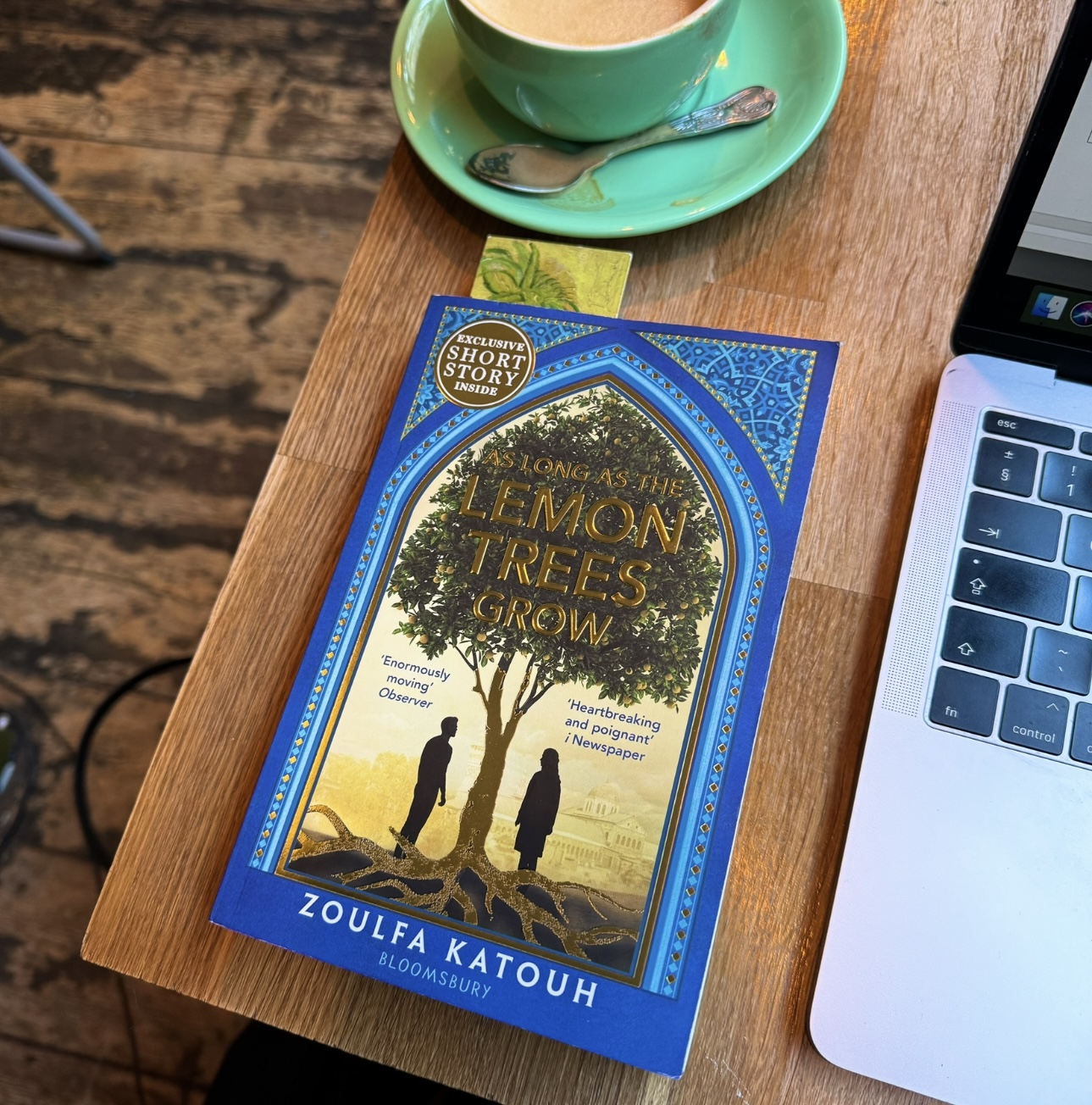

The Syrian war, often misinterpreted or overlooked due to its perceived complexity and the fragility of the region, is a significant conflict in international relations, one whose reverberations continue to resonate around the world. Its impacts ripple across the West, contributing to the rise of populism, xenophobia, and Islamophobia, as well as fuelling the global refugee crisis. Yet, while the wider political discourse is dominated by proxy wars, sectarian rhetoric, and the ongoing War on Terror, Zoulfa Katouh’s heartbreakingly, beautiful debut novel As Long as the Lemon Trees Grow offers a deeply human and intimate portrayal of the Syrian revolution.

Standing in stark contrast to the grand geopolitical analyses that often overshadow the personal stories of conflict, the novel centres on the life of Salama Kassab, a young pharmacy student volunteering at Zaytouna Hospital. Set against the backdrop of the siege of Homs, which began in May 2011, and amid the constant influx of wounded patients, Salama’s loyalty to her war-torn country is tempered by an increasing desperation to escape, especially before her sister-in-law, Layla, gives birth. As she navigates through the daily horrors of war, evading bombings and surviving military assaults, Salama is not only forced to confront the immediate, physical dangers that surround her but also to reckon with the shifting landscape of her moral compass. Her journey becomes an internal war, where the boundaries between a deep sense of duty to her country and the instinct for self-preservation blur. When she unexpectedly crosses paths with Kenan, Salama begins to question the very nature of freedom, survival, and the meaning of “home” in a world where everything seems to be fractured.

Through her story, Katouh serves a lesson to political pundits and their long-winded, often orientalist commentaries by bringing us back to the simple, fundamental demands that lie at the heart of the Syrian revolution: the yearning for freedom, dignity, and the basic will to survive. Katouh’s novel does not engage in macropolitics, but rather, it focuses on the deeply personal and the profoundly human. It centres on spectacularly unremarkable peoples, ordinary Syrians whose lives have been upended by war, yet whose resilience encapsulates the spirit of a nation. In doing so, As Long as the Lemon Trees Grow offers a narrative of quiet heroism. Like so many Syrians, the characters in the novel are not revolutionaries in the conventional sense but individuals caught in the turmoil of war. Yet, they represent something far larger: the collective will of a people who dared to demand freedom from a violent regime.

What makes Katouh’s novel particularly clever is its subtle exploration of nature as a symbol of survival and resistance. Writers have analysed the book from an ecocritical perspective, focusing on how the natural environment is central to the narrative. As Long as the Lemon Trees Grow showcases how the land itself becomes intertwined with the fate of its people. In the aftermath of war, when everything seems to be crumbling and colour appears to be missing from everyday life, nature persists. Even amidst the devastation of Homs, the city where Salama lives and works, the natural world, symbolised partly by her constant recollection of natural remedies to soothe her nerves and quiet her troubling thoughts, reminds us of both fragility and strength. Nature’s survival in wartime is portrayed not as a passive force, but as a symbol of hope and continuity, a reflection of the Syrian spirit that refuses to be crushed by violence. In moments of despair, nature offers a glimmer of possibility. As Salama reflects in the novel, “And we will come back…Insh’Allah we will come back home. We will plant new lemon trees. We will rebuild our cities, and we will be free” (p. 245). This passage is more than just a hopeful prayer; it is a defiant declaration that despite everything, despite the destruction and the pain, there is still hope for rebirth, for a return to the soil that was once loved and nurtured. The reference to lemon trees is not just about the resilience of nature but about a longing for restoration, for a Syria where the simple act of planting trees symbolises a return to normality, peace, and self-determination.

The personal stories that weave through the broader narrative of resistance in As Long as the Lemon Trees Grow resonate deeply with the real-life figures who gave everything for the cause. A patient at Salama’s hospital mentions the news of Ibrahim Qashoush’s murder, the revolutionary singer from Hama whose anthems galvanised many to continue the fight. Qashoush was killed at the hands of the Assad’s military when they cut his vocal cords to silence him, highlighting the regime’s cruel attempts to quash even the simplest expressions of defiance.

Similarly, the character of Kenan, who records and shares the regime’s brutalities online, evokes memories of Bassel Shehadeh, the bright-eyed Syrian filmmaker who abandoned his place at Syracuse University to return to Syria and document the revolution. Driven by an unwavering love for his country, Shehadeh could not bear the thought of telling his future children that he was abroad while his homeland was torn apart by war. He dedicated himself to training activists and citizen journalists, teaching them how to document the atrocities through video. Shehadeh was killed in 2012 while filming in Homs when government forces began shelling a neighbourhood where rebels had taken refuge in civilian homes.

In the novel, when Salama is told that her brother is alive but imprisoned in Sednaya, known as the “Human Slaughterhouse,” her anguish is all too understandable. The torment of knowing that he survives in such a brutal place, where survival itself is worse than death, is a reality echoed in the testimonies of those who have endured its horrors. Mazen al-Hamada’s story is one of many tragic accounts that will emerge from Sednaya. A prominent activist from Deir ez-Zor, Mazen had fought for Syria’s freedom since 2011, bringing global attention to the cruelty of the Syrian government. After seeking asylum in the Netherlands in 2014, Mazen returned to Syria in 2020, despite the immense risk. Faced with the dehumanising bureaucracy of the Dutch immigration system and being given promises of clemency in Syria, he decided to go home. He disappeared later that year. As rebels began releasing prisoners in the first days of Assad’s fall, Mazen’s body, bruised, burned, and tortured, was found in Sednaya, indicating he had been killed just days before the fall of Damascus. Mazen was so close to experiencing a free Syria, to witnessing a Syria without the Assads, a Syria for all Syrians. His death, like that of countless others, stands as a powerful testament to the sacrifices made by those who risked, and ultimately gave their lives, in the pursuit of truth, freedom, and justice.

As Long as the Lemon Trees Grow is a reminder that the revolution was not only about overthrowing a dictator but about claiming the right to be heard, to be free, and to rebuild a nation shattered by war. By focusing on the intimate, personal experiences of its characters, As Long as the Lemon Trees Grow serves as a necessary counterpoint to the often impersonal and distant political analysis that characterises discussions of the Syrian conflict. Katouh’s literary skills challenge us to reconsider what constitutes politics and history. It reminds us that they are not solely crafted in the halls of power or within the corridors of government. Politics and history are also found in the quiet, fleeting acts of resilience – on crowded streets, in casual conversations on the way to the market, and in the shared songs and dreams of a people determined to be free. These transient moments, often dismissed as too insignificant for any serious analysis, have the potential to spark radical new possibilities, inviting people to reimagine societal structures and redefine what constitutes community and justice.

The future political landscape remains uncertain, but for now, a dictator has been toppled, families are beginning to reunite, and Syrian cities and civil society are slowly rebuilding. This shift in context allows the book to serve as a reminder of the long road ahead while also offering a sense of closure for those who have lived through the turmoil.

On the first anniversary of the uprising, Salama underscores the significance of the revolutionary Syrian flag:

“The revolution’s flag is flying high over our heads, and it makes me dream of a day when we can raise it in our schools, proudly singing the national anthem. When it will represent us worldwide. For now, this flag is our shield against the cold winters, the bombs falling from the sky, and the bullets that tear into our bodies. In death, it is our shroud, our corpses swaddled in it as we return to the soil we vowed to protect” (p. 259).

The revolution’s flag, once a symbol of defiance and resistance, has evolved into a beacon of hope — much more than just a political emblem. It became a protective shield for Syrians, a blanket of solace amidst the violence that rained down upon them. Perhaps it is a selfish comfort, but I am grateful to have read the novel after Assad’s fall. Now, having finished it, I can take solace in knowing that Salama can return to the home she never wished to leave, raise her flag proudly above Syria’s skies, and plant as many lemon trees as her heart desires.

Thahmina Begum Thaniya is an Academic Tutor in the School of Law, Policing and Social Sciences.

- Photo of people gathering by Ahmed Akacha: Pexels

- Photo of lemon tree by Oleksandra Zelena: Pexels

Politics

Politics Laura Cashman

Laura Cashman 4160

4160