Dr Natalia Slobodian considers the implications of the attack on the Nova Kakhovka Dam.

For over a year, the Ukrainian people have demonstrated great resistance, heroism and victories, experienced military crimes in Bucha and fierce fighting for Bakhmut, restrained their tears and fostered indescribable hatred for the Russian invaders. It seemed that Ukrainians had already gone through the most terrible trials at the hand of the Russian army but the breaking news from 6 June made me speechless. By blowing up the Nova Kakhovka Dam, Russia has committed the next act of environmental terrorism, resulting in a humanitarian and ecological disaster which may have global ramifications.

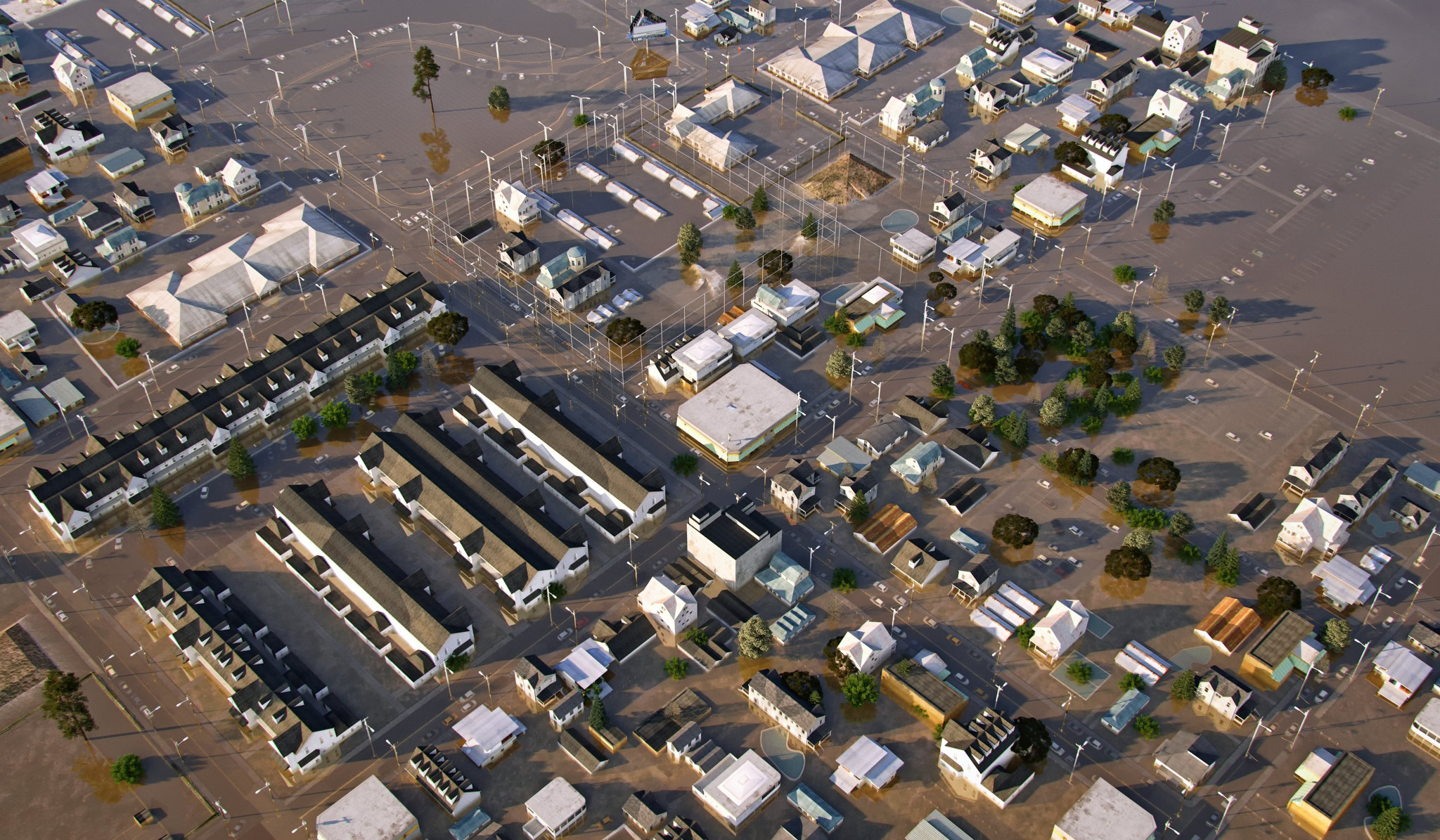

600 sq km were flooded on the first day of the tragedy, equivalent to an area of double the size of the Canterbury district. Thousands of people lost their houses, hundreds of thousands of residents of Kherson, Mykolaiv, Kryvyi Rih, and Dnipro have limited access to drinking and process water, and millions of hectares of farmlands have become unusable or contaminated. The explosion released at least 150 tons of oil into the Dnipro River, and 333 species of animals, birds, and plants classified as protected species are at risk of extinction.

It is too early to fully assess the scale of destruction but the first data that has emerged is shocking. A preliminary assessment of the Ministry of Environmental protection estimates that the ecological damage amounts to £1 billion, not including material losses.

Russia seems to have a special hatred for this region, which they first occupied, then shelled, and now flooded!

Meanwhile, environmental protection has become a value and key priority of the European Green Deal, and numerous ecological standards and rules are integrated into Directives and Regulations that form a framework for business. Unfortunately, the environment and the climate as the silent victims of violent conflict are often directly harmed by hostilities through the use of special weapons targeting industrial facilities and infrastructure or the use of so-called “scorched earth tactics”. Despite this, the environmental and climate damage caused by violent conflict is for the most part not the focus of criminal investigation and responsibility.

The dam’s destruction also creates additional problems for Kyiv because of energy security issues. The country was already running low on electricity before it lost the Kakhovka hydroelectric station. In addition, the reservoir provided cooling water for the Russian-occupied Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant. Without enough water, the plant could suffer a dangerous meltdown. The facility’s Ukrainian operating company Energoatom anticipates that currently reservoirs provide enough water, but water levels are dropping dramatically and circumstances may deteriorate rapidly. If the level falls below 12.7 meters it becomes impossible to pump water into the plant’s cooling circuits, giving plant operators just days to find a solution. The IAEA chief said that there was no immediate risk but that it was essential that a cooling basin remains intact to provide enough water to cool the temporarily closed reactors. In the event of a meltdown, radioactive material could travel several hundred miles – well beyond Ukraine – depending on the weather and other factors.

Ukraine is exploring various avenues that will allow it to hold Russia accountable for the environmental damage Russia’s attack has been causing to Ukraine. The crime of ecocide has been included in the Ukrainian criminal code in 2001. At the global level, the International Criminal Court does not currently recognize ecocide as a crime despite growing pressure to do so. Currently, Article 5 of the Rome Statute of the ICC states that it can consider “issues relating to four categories of crimes: genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and the crime of aggression”. In the discussion on the international legal regulation, ecocide has been mainly considered in the context of armed conflicts and war crimes.

It is also important to note that on 25 January 2023, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe adopted a resolution on the negative impact of war on the environment. The parliamentarians made a clear step towards defining the crime of ecocide, emphasizing the importance of such a definition for both national and international legislation. The resolution recognizes the need to amend the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court and add ecocide as a new crime. If these changes are implemented, Ukraine will be able to sue Russia in the ICC for crimes against the environment – destroyed ecosystems, contaminated soil, burned forests, etc. Moreover, President Zelenskyy keeps ecocide high on the agenda in his 10-point peace plan, which is also one of the country’s preconditions for entering peace negotiations with Russia.

Russia in the 21st century remains a threat on multiple levels, including not only military, geopolitical and humanitarian challenges, but also man-made environmental and technological disasters with transboundary and global effects. The Kremlin thus shapes the demand for globally security-related decision and the UK, EU, and USA as well as international authorities should not merely quickly react but also look for asymmetric solutions. Consequently, the global community should move to create a multi-level deterrence system on the basis of already existing structures and mechanisms, which are ready both to respond to pre-emption and to signal to a potential aggressor that, in the case of war, compulsory compensation for environmental and climate damages will be set in action.

Dr Natalia Slobodian joined the Politics and IR team as a researcher in October 2022. Previously Natalia was Head of Department Climate Change at the energy company DTEK and head of Corporate think tank SE NPC Ukrenergo. She has more than 10-years’ experience as senior researcher and lecturer at Taras Shevchenko Kyiv National University.

Politics

Politics Laura Cashman

Laura Cashman 2245

2245