As the Covid-19 pandemic continues to dominate political debate, Dr Paul Anderson examines the intergovernmental interaction between the different governments in the UK, and argues that while tensions may now be appearing concerning lock-down strategies, intergovernmental relations have generally proceeded in the spirit of cooperation with the governments closely working together.

In recent years, the UK’s experience with intergovernmental relations has been marked by prolonged periods of mistrust, suspicion and outright hostility. The tragedy of the Covid-19 crisis, however, seems to have initiated a new chapter in intergovernmental interaction. Tensions around EU withdrawal and its constitutional, economic, legal and political ramifications have not gone way, but the UK approach in managing the ongoing pandemic has been one of cooperation; a common front in times of unprecedented uncertainty.

In the UK’s multi-level system, public health is largely the responsibility of the devolved nations, each of which has developed its own distinct laws and policies. At the very beginning of this crisis however, there was acknowledgement from all governments in the UK that an efficient and effective response would necessitate close cooperation. The various First Ministers representing Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales participate in the UK’s government’s COBR meetings, while the chief medical officers in the different nations continue to work together, too.

This UK-wide approach was endorsed in the collaboratively produced Coronavirus ‘action plan’ published in early March, as well as the Coronavirus Act 2020 which proceeded in the UK Parliament with the legislative consent of the 3 devolved assemblies and legislatures. Further, Boris Johnson’s statement on 23rd March announcing lockdown measures was followed by immediate and supportive declarations by the various First Ministers. This common front among the different governments sensibly seeks to diminish the risk of mixed messages and thus save lives. The Prime Minister, other UK officials and the First Ministers take part in daily briefings, and while some differences in terms of timings and communication have emerged, support for a UK-wide approach remains high.

Much like the evolution of devolution itself, there have been some divergences in the approach. The Scottish Government, for example, was the first government to impose a ban on gatherings of more than 500 people while school closures were announced first by the Northern Irish Government, albeit the other nations quickly followed suit. Initially divergent changes also applied to the holding of criminal trials in Scotland and Northern Ireland (where justice is a devolved power), while more recently the Scottish Government was the first administration to suggest wearing face coverings when shopping. Further differences may also emerge regarding lockdown exit strategies.

If you are interested in these issues, why not check out our Politics programme, where I teach on our undergraduate and postgraduate degrees?

The Scottish Government, for instance, was the first to publish its exit strategy, followed by the exit framework outlined by the Welsh Government. Interestingly, however, while the exit plans of the Scottish and Welsh governments are specific to their territories, the notion of a UK-wide approach is emphasised. Indeed, following the publication of the Scottish strategy, UK Health Secretary Matt Hancock, underlined that the Scottish Government’s plans were much in line with the tests set out by the British government. Differentiated strategies have not led to completely distinct approaches.

In recent weeks, however, the devolved governments have made clear that while the UK-wide approach is the preferred option, disagreements regarding lockdown exit strategies may entail different strategies. Mark Drakeford, Welsh First Minister, for example, has made clear that lockdown in Wales may end quicker than other parts of the UK, while Nicola Sturgeon, his Scottish counterpart, has not ruled out extending the lockdown north of the border even though it may be eased elsewhere in the UK. Arlene Foster has made a similar statement regarding Northern Ireland.

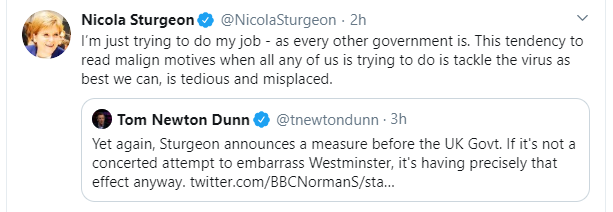

Such divergence has not gone completely unnoticed. Controversy ensued, for instance, when the Scottish Government chose to name the temporary hospital set up in Glasgow, the Louisa Jordan Hospital rather than follow the Nightingale naming convention in England. In addition, political commentators (see Tweet below) have been equally critical of the divergent communication and timing approaches of the Scottish Government. Despite two decades of devolved governance in the UK, such critiques are unwarranted and fail to understand the workings of devolved decision-making. In short, they betray a unitary rather than devolved/federalised understanding of the UK.

The unique status of Northern Ireland and its border with Ireland, not to mention the power-sharing credentials of the Northern Irish executive, necessitates cooperation not just with the UK government in Westminster, but the Irish government in Dublin too. This has seen calls from some parts for an all-island approach and exit strategy in order to minimise a resurgence of infection. The border between Ireland and the North has been a hugely controversial sticking point in the Brexit debate, but as this global pandemic has shown, viruses don’t respect borders. Politics aside, synchronisation and collaboration will be the necessary orders of the day.

So far, management of the Coronavirus crisis in the UK has seen close cooperation among the different levels of government. Cooperation during the current pandemic has not been frictionless but for the time being party politics has been replaced by genuine concern and willingness to work together. As noted earlier, this stands in complete contrast to the experience of intergovernmental interaction in the preceding years. Behind the common front of the pandemic, however, tensions remain regarding the EU withdrawal timetable, as well as the Scottish Government’s continued push for a second independence referendum. The SNP may have temporarily paused its referendum-push but will be well aware that the cooperative interaction and solidarity with the UK government necessitated by the pandemic as well as prolonged periods of (economic) uncertainty may weaken the case for independence.

There is no doubt that the experience of the pandemic will continue to change life as we currently know it, and while all governments issue friendly warnings about ‘a new normal’, only time will tell if intergovernmental cooperation and collaboration between the governments in the UK will be part of that too.

Dr Paul Anderson is Lecturer in Politics and International Relations at Canterbury Christ Church University, and co-lead of the UACES-JMCT Research Network, (Re)Imagining Territorial Politics in Times of Crisis. His research and teaching focuses on Territorial Politics, with particular focus on Spain and the UK, devolution and independence movements. He teaches modules on our undergraduate and postgraduate degrees and welcomes applications from PhD students interested these themes.

*This blog was published as part of the UACES-JMCT Research Network’s series on Territorial Politics and Covid-19

Politics

Politics Laura Cashman

Laura Cashman 1126

1126