Data and hard facts are increasingly disputed by the media and the government during the coronavirus crisis. Dr Soeren Keil reflects on the never-ending debates about the benefits of qualitative and quantitative research methods, and argues that too narrow a focus on numbers can be dangerous from both scientific and political political perspectives.

I remember when I studied Politics in my 2nd year of my undergraduate studies, I was obliged to take a class on research methods. The Professor, a strong supporter of quantitative research methods, kept emphasising not only the objective value of these methods, but also highlighting the fact that most qualitative methods allow far too much room for interpretation in their findings.

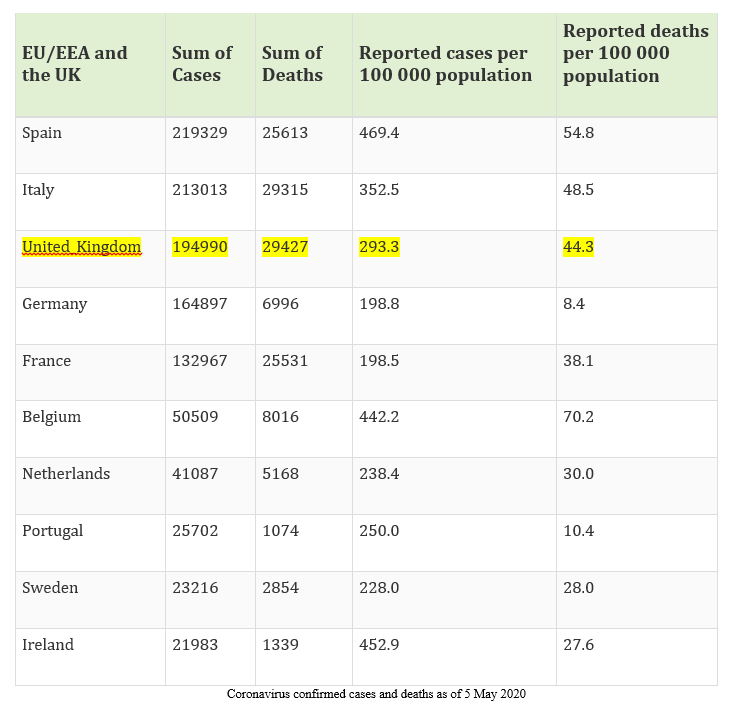

Fast forward some 18 years, and here we are, in the middle of a global pandemic, stuck at home, in the country that has the highest death rate in Europe. Or does it have the highest death rate?

When looking at raw data, the UK has now the most deaths related to COVID-19, the illness caused by the coronavirus, in Europe, and 2nd in the world only to the USA.

Source: European Centre for Disease Control, https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/cases-2019-ncov-eueea

However, the UK government has been quick to point out that the data as such might a) not be correct as different countries use different counting mechanisms, and b) that absolute numbers of deaths for each country are not a useful measurement to assess how hard a country is hit, or how a government should be judged in their response. Likewise, the BBC highlighted that Italy has a smaller population than the UK and that other factors should be considered as well. Of course, they forget to mention that Germany has a substantially larger population but less than one third of the deaths of the UK (I will not even mention China here…).

This is not the first time that numbers have been questioned and openly challenged. When the government announced on 1st May 2020 that it met and exceeded its target of 100,000 coronavirus tests by the end of April the previous day, it counted 30,000 tests which were sent out to patients to test themselves and return. Not all of these tests were returned, and there is no evidence that any of them had been tested by the 30th of April – yet, in the eyes of the UK government, and especially the UK Health Secretary it was mission accomplished. For many observers however, this seemed like a very flexible and unscientific way of counting, and the government’s aim to maintain this figure has been missed repeatedly in the first week of May.

If you are interested in these issues, why not check out our Politics programme, where I teach on our undergraduate and postgraduate degrees?

As the dispute continues between those arguing that the late reactions of the UK government at the beginning of the crisis, and structural failures within the NHS (after years of underfunding the health service and a lack of preparation before the outbreak) are to blame for the UK’s overall poor performance, and those questioning data collection and reliability – thereby defending the UK government and its actions in the coronavirus crisis, there is a heated debate about what these figures mean and how one can compare. There is also a risk that the UK’s government wants to shift blame and avoid responsibility for this public policy failure. But it seems as if there is another strategy here as well – one which disputes scientific evidence and facts as such. By disputing absolute figures, and questioning the way countries count, the UK is playing partly to its own superiority complex (Foreign Minister Raab literally said that the UK Office of National Statistics is the best in the world), but also wants to highlight that within the failure, there are some good bits. We might have a high number of deaths, but at least we count them accurately, seems to be the message here.

And all this got me wondering. My research methods Professor was wrong after all. Quantitative data can be disputed as much as qualitative findings. Absolute raw numbers mean nothing without context, without clear descriptions of how these numbers have been arrived at, and what they mean for cases and across cases. The famous apples and pears analogy comes to mind here. While every person that dies as a result of COVID-19 is a tragedy, the current debates about the number of deaths, the number of daily tests and the impact of the crisis as a whole also needs to remind us that behind all of these raw data, there are public policy choices. These choices have consequences. These consequences are reflected in some of the raw data we have today, including overall death counts.

Dr Soeren Keil is Reader in Politics and International Relations at Canterbury Christ Church University and Director of the Centre for European Studies. His research and teaching focus on territorial autonomy, conflict resolution, the Western Balkans and the EU. He teaches modules on our undergraduate and postgraduate degrees and welcomes applications from PhD students interested in these themes.

Politics

Politics Laura Cashman

Laura Cashman 1338

1338