By Professor Amelia Hadfield, Canterbury Christ Church University

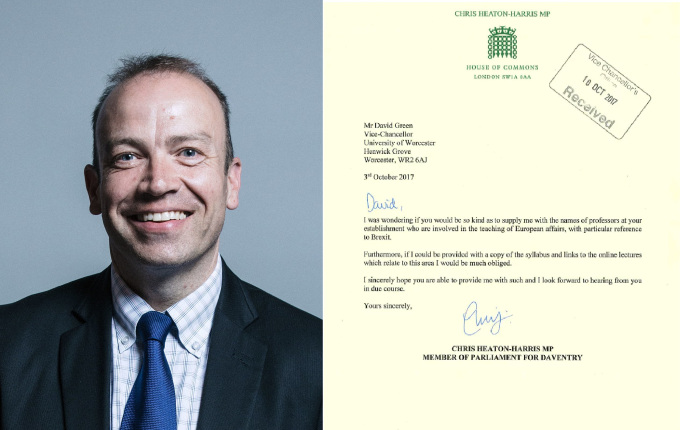

On Tuesday 25th October 2017, The Guardian published an article entitled “Universities deplore ‘McCarthyism’ as MP demands list of tutors lecturing on Brexit”, regarding a letter written by Chris Heaton-Harris, MP for Daventry and Assistant Whip, to UK university Vice Chancellors. In the letter, Heaton-Harris asks for “names of professors involved with teaching of European affairs, with particular reference to Brexit. Furthermore, could (I) be provided with a copy of the syllabus and links to the online lecturers.”

At best, the request represents a moment of pure idiocy. At worst, as per Professor Kevin Featherstone, Head of the European Institute at the London School of Economics, it’s “McCarthyite” in nature… “It smacks of asking: are you or have you ever been in favour of remain? There is clearly an implied threat that universities will somehow be challenged for their bias.” [1] The outrage it provoked in universities and academic associations across Britain was impressive, but not surprising.

The general response to the request is twofold.

First – with due respect to Mr Heaton-Harris – NO. Not now, not ever. As per the statement by Alistair Jarvis, Chief Executive of Universities UK (UUK): “This request suggests an alarming attempt to censor or challenge academic freedom. It is essential that universities remain places where free speech flourishes. This means protecting independence in academic study, encouraging rigorous debate and providing opportunities to hear and challenge a diverse range of views.”

In terms of UK legislation: Let’s remember that academic freedom is enshrined in law. As the UUK statement pointed out, “Section 202 of the 1988 Education Reform Act ensures that academic staff have the freedom to question and test received wisdom, and to put forward new ideas and controversial or unpopular opinions, without placing themselves in jeopardy”. The Minister of State for Universities and Science, Jo Johnson, made a tardy but at least accurate contribution, tweeting that “academic freedom… is core to success”, and protected in statute within the Higher Education and Research Act of 2017. In a nutshell? Progressive societies are underwritten by academic enquiry free from political interference. Not academia where university lecturers are placed on a list for ideologically dubious reasons.

In terms of universities in general: Higher education is a bulwark against bias, prejudice, misinformation and error. Higher education not only operates upon the key prerogative of academic freedom, it does so because it is charged with ensuring clear-sighted, evidence-based, open-minded thinking that can both examine and criticise any given idea. UK universities are as a whole committed to freedom of speech within the law, and to open independent academic debate. Suggesting they are hothouses of subversive thought designed to bring down the state isn’t only sinister. It’s just silly. The University and College Union was quite right to argue that HEIs “must lead the way in defending academic freedom, where received wisdom can be challenged and controversial ideas debated.” Indeed, failing to do so places our universities at risk of failing to protect the hard-won right of freedom of speech. We wouldn’t want that, would we?

In terms of teaching specifically: what lecturers choose to put into their course content is entirely their own business. They make this decision, year in and year out, on the basis of modular learning objectives, assessments, appropriate readings, learning and employability criteria; all grounded on the research expertise of the academic in question (whether a new lecturer or a senior professor). The best teachers present challenging concepts to their students on the basis of a range of readings, theories, case studies, and data, encouraging them to look carefully, critically, at all dimensions, debating the pros and cons of each aspect, in open and thoughtful environment. This constitutes the better part of virtually every academic I know in this country, and beyond.

In addition, module content, course materials, and teaching personnel are entirely matters for universities themselves. The specific attitude of a given academic vis-à-vis their course content, whether it’s European geopolitics or medieval knitwear can indeed influence how they teach in the classroom, but they’re generally intelligent and skilled enough to point out the difference to their students between their personal opinion of an issues, their overarching understanding of it in academic terms, and how it functions in practical, material and daily political life.

We academics all teach on the basis of our expertise, our research, and with a keen awareness of the duty of care to our students in delivering cutting-edge, challenge, engaging courses that encompass the fullest range of views.

More to the point, course content – from reading lists to power points, from lecture notes to seminar handouts, both hard copy and virtual – are located within termly and yearly structures comprising higher award pathways. These pathways are available to students who are undertaking the rigours of an undergraduate or graduate degree, in a competitive environment, and for which they are assuming both an immediate cost and a long-term debt. Both the quality of this content, and the sheer quantity of course work (e.g. on UK-EU relations) is not something that can be chucked cheekily across the desk of an MP, however dubious the request.

Second. I would advise Mr Heaton-Harris to have a look at what already IS publicly available regarding Brexit content before dashing off rogue requests to baffled vice-chancellors. Since 2016 – and in many cases long before – academics in this country have been in overdrive, publishing peer-reviewed articles, chapters, texts, anthologies, briefing notes, reflective papers, official and unofficial reports, in addition to scores of media and social appearances on Brexit. We are as a group bringing our expertise to bear upon the uniquely challenging situation that is Brexit. We do it because we have the freedom in law to do so, the expertise to comment intelligently, and the courage to think beyond the ideological straightjacket that now threatens the majority of independent thinking in this country, from the government on down.

Why on earth wouldn’t academics be busy with Brexit, and consequently animated at attempts to curtail this activity? Brexit is epochal in its implications. It will impact every sector and field of activity, from business to medicine, from agriculture to education. Academics from across a range of disciplines (not just politics) have for months engaged publicly and openly with local stakeholders, regional and national government, to provide their insights on the emerging challenges of Brexit. Here at Canterbury Christ Church University for instance, we’ve been privileged to work with a wide range of individuals, companies, and entities in producing data-based analysis regarding the local impact of Brexit on Kent and Medway (see our latest reports here). We’ve looked in depth at business and agriculture, and are now examining health and social care, and customs, policing and the border. These reports, and the public events that accompany them are all publicly accessible, clear in their inclusive rationale and their academic objectivity. Nothing nefarious here, I’m afraid, Mr Heaton-Harris.

Nor in the classroom, as intimated above. The MP for Daventry will just have to satisfy himself that UK academia really is representative of the rights and freedoms that are held up as uniquely British values. And he’ll have to deal with the political fallout from his own party, the opposition, at his crass insinuations of academic bias regarding the teaching of Brexit. He and others who subscribe to such views may be surprised at the heated response generated by universities in defence of their role as free intellectual spaces, and academics as guardians of thinking without political interference. Perhaps it’s time for Heaton-Harris to go back to school.

[1] McCarthyism refers to the movement led by US Senator Joseph McCarthy during the Second Red Scare in the 1950’s which saw federal employees and even actors blacklisted on suspicion of being Communists

Politics

Politics Anna Vanaga

Anna Vanaga 1174

1174

Well said. As someone proud to have been one of the first ever Jean Monnet Profs, this DM attack is a continuation of anti EU bullying trotted out over the years since Thatcher pushed for the Single European Market. Monnet stood for pragmatism over political dogma, peace and cooperation to end division in Europe and enable every generation to shape Europe in the light of development. Brexit robs children of something their peers enjoy. Which parents, which students approve of a government doing that? Students have a duty to read the Government’s impact studies…oh dear, they’re suppressed. Why is the question. An answer is awaited. Meanwhile, they – and the public and journalists, MPs and the Cabinet – can read reports on the EU websites, expert evidence to Parliament, speeches and so on and try and decide for themselves. That is what critical thinking and reflection are about. That is what universities do in respect of every subject taught. That is the point of learning, innovation and trying to build a better future for

the common good. Juliet Lodge (Prof)