Mark Bennister (Canterbury Christ Church University), Ben Worthy (Birkbeck, University of London) and Paul ‘t Hart (Universiteit Utrecht) have published a new book on leadership capital, applying their Leadership Capital Index to a series of country case studies.

Understanding and measuring political leadership is a complex business. Though we all have ideals of what a ‘good’ leader should be they are often complex, contradictory and more than a little partisan. Is it about their skills, their morality or just ‘getting things done’? And how can we know if they succeed or fail (and why?). From Machiavelli onwards we have wrestled with our idea of what a perfect leader should look like and what makes them succeed or fail.

Understanding and measuring political leadership is a complex business. Though we all have ideals of what a ‘good’ leader should be they are often complex, contradictory and more than a little partisan. Is it about their skills, their morality or just ‘getting things done’? And how can we know if they succeed or fail (and why?). From Machiavelli onwards we have wrestled with our idea of what a perfect leader should look like and what makes them succeed or fail.

One way to think about comparing and measuring is to consider leadership authority. Taking the idea of ‘political capital’ we can look at what sort of authority a leader is granted and how they choose to ‘spend’ their capital. We can think of political capital as a stock of ‘credit’ accumulated by and gifted to politicians, in this case leaders. Political capital is often used as a shorthand to describe if leaders are ‘up’ or ‘down’, how popular they are and how much ‘credit’ they have in the political sphere. Like with financial capital, commentators and politicians speak of it being ‘gained’ or, much more commonly, ‘lost’. Most importantly, it’s viewed as something finite; you only have so much and it quickly depreciates under pressure of the media, opposition or events. This presents us with alternative method of understanding why political leaders succeed or fail.

Politicians are acutely aware of their finite stock of authority. Having plenty of this ‘credit’ means a leader can lets of things done by spending or leveraging it- think Tony Blair in 1997 or Barack Obama in 2009 when their support, popularity and momentum temporarily made them politically unassailable. They believe they can pass laws, set agendas and dominate the ‘narrative’. Tony Blair, reflecting in his autobiography, spoke of how he was a capital ‘hoarder’, trying not to spend his authority in his early years as Prime Minister:

“At first, in those early months and perhaps in much of that initial term of office, I had political capital that I tended to hoard. I was risking it but within strict limits and looking to recoup it as swiftly as possible… in domestic terms, I tried to reform with the grain of opinion not against it.”

Understanding leadership capital

Academics have defined political capital in a variety of ways. It can be about trust, networks and ‘moral’ or ethical reputation. By incorporating many of these ideas, we are developing a notion of leadership capital as a measure of the extent to which political office-holders can effectively attain and wield authority.

We define leadership capital as an aggregate of three leadership components: skills, relations and reputation. We have worked this is into a Leadership Capital Index (LCI). The Index has 10 simple variables to enable leaders to be scored, using a mixed methods approach to capture both quantitative data and qualitative assessments. You can see our more detail index in our article or here.

The measure of a leader’s skills refers to the whole range of abilities a leader needs, from the communicative to the managerial and cognitive. We look at the power of a leader’s vision, their communication and their popularity. The difficulty for many leaders is that they have, of course, some of these but not all. Both Cameron and Blair for example have been accused of having the communication skills and (relative) popularity, but not the vision. Theresa May appears lacking in both, but has incumbency capital and gains in comparison to the alternative.

Leadership is also a relational activity. Leaders mobilise support through loyalty from their colleagues, their party and the public. Part of the challenge of leadership is to retain these ties for as long as possible or, at least, as one scholar put it, to disappoint followers at rate they can accept. But how they do this can depend on their leadership style (Fred Greenstein’s influential approach gave a psychological framework for assessing style in office). The most obvious and talked about way is through charisma, the Blair or Obama offer of what James Macgregor Burns famously termed ‘transformational’ leadership. But effective leadership can also be through quiet, technocratic competence and delivery, more in the style of Angela Merkel (as Ludger Helms and Femke van Esch show in the book). Leadership needs to suit the cultural norms of the country and the situation, see this discussion of ex (and possible future) Italian PM Matteo Renzi.

Third, leadership is continually judged and ‘sold’ by reputation. Leaders create their own performance measurements – have they done what they promised? Each type of leadership claim sets up its own performance test. We look at whether a leader is trusted by the public, subject to challenge or not and to what extent they control party policy or their legislature (see this article by Michael Rush on the UK).

Looking across these three areas in combination allows us to understand how they influence each other in ‘positive’ or ‘negative’ cycles. Successful leaders communicate, achieve aims and strengthen relations and reputation. Failed leaders poorly communicate or never map out a vison, then often lose confidence, control and credit.

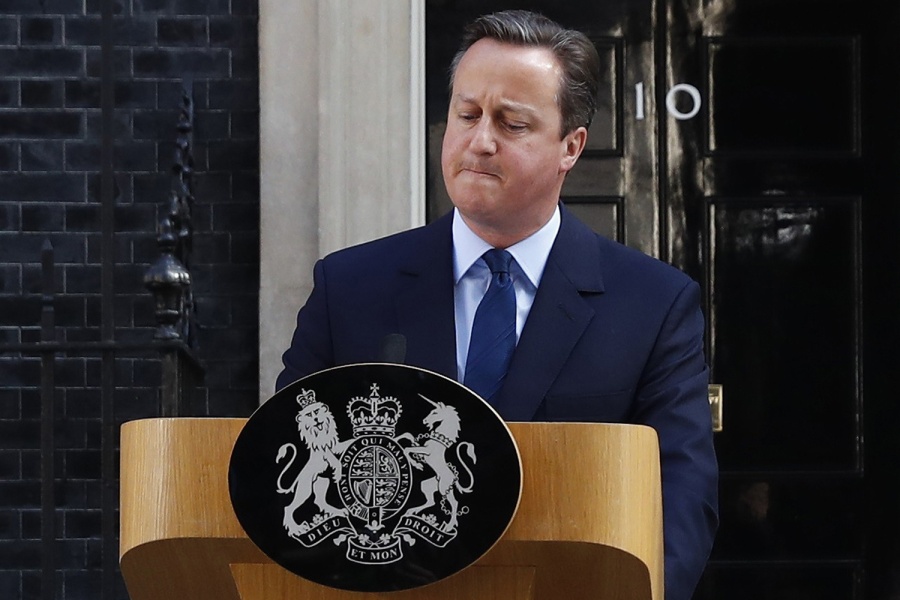

David Cameron’s EU strategy 2013-2016 provides a neat mini-example of capital loss, where he gambled his capital on a series of high stakes policies with diminishing returns. His failure to communicate his European vision, and tendency for a series of ‘Hail Mary Passes’ with a promised 2017 referendum and EU reform, eroded already ambivalent relations with parts of the Conservative party. This in turn has left him with less control over EU policy or parliament as party rebels exerted more and more influence. So attempts to regain the high ground on the EU debt or by making ever more promises on immigration weakened his capital (you can read a more detailed assessment of Cameron here). This led directly to Cameron losing the referendum and resigning in June 2016.

Where next for leadership?

The idea of leadership capital offers one possible way of understanding how leaders succeed and fail. We hope our LCI can provide one way to measure and identify the ebb and flow of the leadership trajectory over time. In analysing cases within countries such as Canada, Australia and the United States but also Spain, Sweden the Netherlands and Hungary we can track the trajectory draw some general observations across the cases. We also hope it can be used comparatively beyond our cases to evaluate leadership capital at sub national level as well as cross national.

However, while the framework provides a neat lens, we recognise that all leaders can be helped or hindered by structural advantages or disadvantages, from different levels of trust to powers of the office. Different political systems give leaders less or more control and greater or lesser power, most US Presidents would probably happily swap for the power of a UK Prime Minister or French President. The wider environment also offers opportunities or limitations-war, peace or crisis all shape a leader’s influence.

There is also the fascinating issue of comeback. If all leaders only have a limited ‘stock’ what of those who bounce back? Bill Clinton, Tony Blair (to an extent) or John Howard all managed to turn around their political fortunes and reinvigorate their leadership. Winston Churchill may be the prime example of leader who squandered skills, reputation and relations over and over until late in his life-his career up until 1939 was famously described as a study in failure.

Churchill himself spoke of how politicians ‘rise by toil and struggle’ and remain caught in a paradox whereby ‘they expect to fall: they hope to rise’. Perhaps leadership capital can help us to understand why and how this happens.

_________________________________

Mark Bennister, Ben Worthy and Paul ‘t Hart are editors of a new collection of case studies The Leadership Capital Index: A New Perspective on Political Leadership published by Oxford University Press. You can read the introduction here and find out more on leadership capital on their blog.

Politics

Politics Anna Vanaga

Anna Vanaga 1435

1435