By Dr David Bates, Director of Politics and International Relations at Canterbury Christ Church University

‘Look, all I want is for things to go back to the way they used to be. Back when the villagers were afraid of me and I can take a mudbath in peace. When I could do what I wanted, when I wanted to do it. Back when the world made sense!’

(Shrek from Shrek Forever After, DreamWorks Animation, 2010).

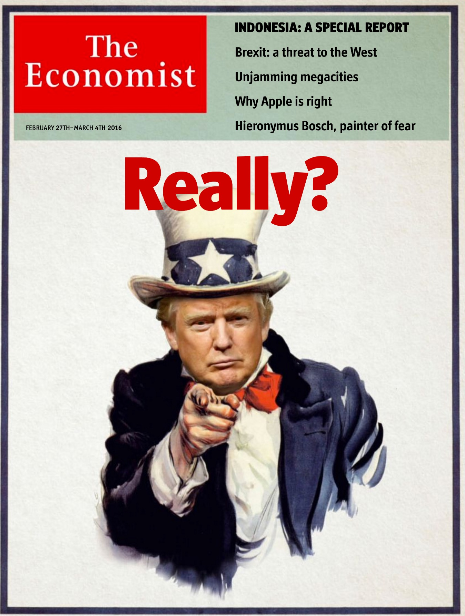

I have noticed a lot of discussion on social media platforms pertaining to the historical significance of Donald Trump’s victory. Many have compared the moment which delivered the soon to be President Trump to the 1920s and 1930s – that is the birth of fascism.

There do seem to be many similarities between Trump and fascist politicians from history. Such similarities include:

- Anti-migrant sentiment and racism – we might characterise this as scapegoating

- Aggressive sexism and deep seated misogyny

- A nostalgic reimagining of the past, invoking a ‘greatness’ which can be reactivated

- A fictitious affinity with the ‘man in the street’; Trump has stated that he gets on much better with taxi drivers than politicians

- The characterisation of all those with whom one disagrees as traitors

- A level of insatiable desire for power which it is difficult to differentiate from psychopathy

- A love of size and vulgarity in architecture, in relation to which it is difficult not to make Freudian connections

And this is not to mention the preference for expensive suits and bad haircuts!

However, there is an extent to which the conjuncture which brought us to this moment is more dangerous than the situation of the 1920s and 1930s.

The financial crash of 1929 was a key point of crisis for international capitalism. This crisis helped set humanity on the path to the Second World War and the destruction of many of the embryonic systems of global governance created after the First World War. As severe as it was, the financial crisis did not challenge the technological basis of the mode of production as such.

The consolidation of contemporary neo-liberal capitalism has resulted in the following:

- The technological transformations which have devastated ‘traditional’ working Industrial labour has been transferred significantly to the Far East. The nearest thing to a factory in many cities may be a call centre or a nursing home.

- The political transformation of the structures of global governance into disciplinary mechanisms which – though this is not their only function – reinforce market norms.

Trump offers a ‘vision’ of America based on a time when these shifts had not yet occurred; when the ‘world made sense’.

The neo-liberal ‘capture’ of the structures of global governance is to an extent challenged by Trump – but from the perspective of an often-contradictory right-wing libertarianism. Along with his supporters, he has attacked NATO and the United Nations for failing to uphold ‘American interests’, and for challenging American exceptionalism.

But Trump does not want an end to neo-liberal capitalism as such. He is no enemy of big business. His ‘alternative’ to ‘Obamacare’ will no doubt be a demonstration of this.

Apart from some public work programmes – for example transport infrastructure – which will be necessary if he is to meet his (forced?) repatriation targets, there will not be an expansion in sustainable employment opportunities. There will be no reopening of factories. There will be no return to the 1950s.

What is more likely is that there will be a slow recognition on the part of key aspects of his constituency that their prospects are not improving. However, Trump – as with all right wing populists – will blame the so-called enemies of the nation. It will not be Trump’s fault. It will be the fault of the Mexicans that he has not yet deported. It will be the fault of African Americans who Tea Party activists consider have gained too much power since the civil rights movement. It will be the fault of working women. It will be the fault of liberals. It will be the fault of environmentalists, etc., etc.

The only way in which right wing populism can function is by the constitution of an ‘Other’ which gives a presence to the nostalgic historical fiction on which it is based.

Unlike short term – though devastating – economic depressions, the global restructuring of capitalism means that there simply will be far less ‘traditional’ manual jobs as a proportion of available employment. Communist thinkers in particular have argued that the technological advance on which such transformation is based would enable an expansion of human leisure time, and hence human flourishing. However, this was only possible with the radical critique and negation of the structure of private property accumulation. Clearly Trump is no communist! (Indeed one of his supporters Newt Gingrich has called for a new House Un-American Activities Committee!)

In his Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Karl Marx argued that Bonaparte’s populism was possible because of the inability of the French peasantry to represent their (perceived) economic interests. Marx wrote:

‘They cannot represent themselves, they must be represented. Their representative must at the same time appear as their master, as an authority over them, an unlimited governmental power which protects them from the other classes and sends them rain and sunshine from above.’

The existential crisis currently being felt by Trump supporters cannot be resolved by Trump. It can only be resolved by an end to ‘Trumpism’. Yet Trump may get stronger as this crisis persists; right wing populism gains its power through the discovery of new enemies. This is a spiral of hatred and decline in relation to which it is difficult to imagine an exit!

The Trump time-machine which some want to take them back to the 1950s – itself a frightening wish – may have returned us in a certain sense politically to the 1930s. But it is difficult to see how the current technological structure of the global economy can enable us to escape the new fascist crisis, especially if Trump continues when in office to refuse the authority of all institutions of global governance.

How can we get out of this terrible cycle? Most people would acknowledge that the Democrats chose the wrong candidate for 2016. It is not possible to stand an unpopular ‘liberal establishment’ candidate against a right wing populist and win. The affective turn of politics in recent years attests to this. But left-wing populists – as frightened by this as the agents of global capital may be – do stand a chance.

Sanders tapped into a rich seam of dissatisfaction; Trump – unfortunately – was able to mine this for the right. Yet, while left-wing populism has the potential to bring humanity back from the brink, it is not itself a firm basis on which to build an emancipatory politics beyond capitalism. No political system can satisfy fully the desires of ‘the people’, but the mobilisation of the insatiability of populist desires points to the real contradiction of the populist moment. This contradiction can only be transcended once we go beyond this (dangerous) moment.

To cite Alain Badiou: ‘Emancipatory politics always consists in making seem possible precisely that which, from within the situation, is declared to be impossible’. (Badiou, 2001: p. 121).

Politics

Politics Anna Vanaga

Anna Vanaga 945

945