*It is not guaranteed that all points made in this comment piece are true!

By Dr David Bates, Director of Politics and International Relations,

Canterbury Christ Church University

According to the common view, we have entered a period of post-truth politics. What is meant by this term is however somewhat ambiguous.

From within the socialist tradition – at least from the time of Engels – ‘True’ speech could be differentiated from false speech. False speech was the outward expression of false consciousness; false consciousness was a product of ideological inversion – in this case the ideological inversion produced in the context of the capitalist mode of production. As Engels – writing with Marx – first argued in The German Ideology: ‘the ruling ideas in an epoch are the ideas of the ruling class’ (Marx and Engels, 1845).

Soviet political propaganda took this claim seriously. But where Marx wished to abolish all forms of ideology, and the social conditions in which they were grounded, Soviet propaganda sought to manipulate the ‘Truth’ in order to keep an odious political system in power. For this reason, the Party apparatus invested huge resources into generating false data that would continue to underpin the grand lies of the State. Accordingly, Soviet propaganda did not challenge the epistemological basis of ideology. The power of ‘Truth’ was acknowledged, hence the huge commitment given to the reproduction of lies.

The Brexit vote in the UK, and the current American Presidential elections prima facie suggest a different kind of politics, with a change in the truth function at its basis.

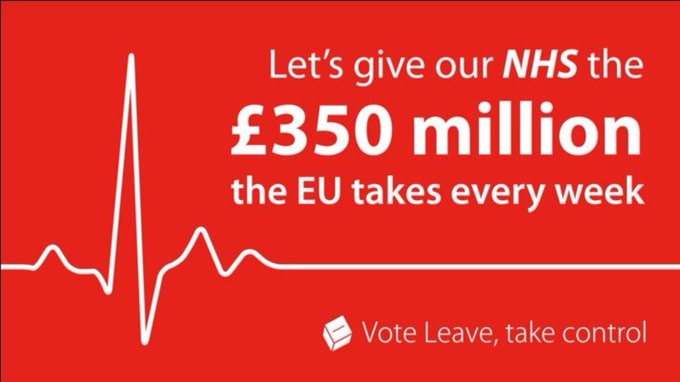

I remember approaching a Leave campaigner on a stall in Canterbury High Street in the run up to the referendum. Before I could utter a word – and knowing who I was from a previous debate at CCCU – he said ‘let me share MY truth with you’. This bold (and I think unconscious) post-structuralist utterance, I must admit, took me aback! The literature on the stall was explicit in its refusal to engage with an ‘evidence based’ political debate. As with much – though by no means all – Leave literature, it instead opted for the manipulation of the complex quasi-Freudian fear of many British subjects towards ‘migrants’. The poster sponsored by Nigel Farage in the final days of the campaign was, by any standards, shocking; Farage considered it perfectly acceptable to invoke Nazi imagery, in order to persuade the British public that, if they did not vote to leave, their small island would be swamped by bands of dark skinned, foreign criminals.

The Remain campaign’s philosophical stance was to an extent more ambiguous; Truth base evidence was used to invoke fear and derision. Brexit would produce a form of catastrophe unknown to the British people in peacetime; all the ‘economic indicators’ suggested this. And the majority of the British people were simply too stupid to understand the ‘facts’ of the case. Better therefore simply to terrify them at least into abstention.

After the result, the responses from both sides were appalling. Those with strong anti-migrant sentiments became even more vociferous, while some remain supporters derided the ‘estate vote’ for its stupidity and ignorance.

(‘Project Fear’ was to this extent a project of each side. The British population were mobilised by elites, whether in or out. However, on an affective level, the Leave side proved more persuasive.)

In the American Presidential campaign, a comparable development seems to be occurring. Trump – armed with the power of assertion – literally says whatever he thinks will gain votes. The large media corporations – desperate to boost their circulation, whatever the cost – are complicit in the process (despite Trumps often bizarre claims to the contrary). The ‘grass roots’ of Trump’s support do not think it necessary to argue on the basis of the evidence. In a hilarious while simultaneously depressing ‘report’ from the Daily Show, a so-called ‘birther’ argues that we cannot trust Obama’s claim to be born in the US because the only witness was his mother, and she of course is not a reliable witness, owing to her bias. When asked to substantiate the evidence base of her claim, she declares that she ‘believes it’ – in part as a result of what she has read on the internet. (Trump of course is well-known to be a ‘birther’. Regarding Obama’s birth certificate, he stated: ‘There is something on that birth certificate — maybe religion, maybe it says he’s a Muslim, I don’t know. Maybe he doesn’t want that. Or, he may not have one’ (see also here).

Hillary Clinton’s campaign strategy is not so dissimilar to the Remain campaign in the UK. Appeals are made to credibility based in experience, and to knowledge of global affairs. But fear too is central to the Democrat campaign. Here, the object of fear comes to be personified in Trump himself – ‘if this crazy megalomaniac gains the reins of power, we are all doomed’. (One of my students once characterized Trump as the Republican id. As students of psycho-analysis know, the id is a bundle of desires with no concern with reality, and lacking morality!)

Supporters of Trump are characterized as ‘deplorables’. To quote Clinton in full:

‘To just be grossly generalistic, you can put half of Trump supporters into what I call the basket of deplorables… Right? Racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, Islamaphobic, you name it…And unfortunately, there are people like that and he has lifted them up. He has given voice to their websites that used to only have 11,000 people, now have 11 million. He tweets and retweets offensive, hateful, mean-spirited rhetoric.’ (Source: LA Times)

In his book Contingency, Irony and Solidarity, the American philosopher Richard Rorty claimed that in ethical discourse ‘anything can be made to look good or bad by being re-described’ (Rorty, 1989: p. 74). The trouble with Rorty’s philosophical claim is that it pays no attention to the relations of power which shape discursive practices and hence truth claims (see Geras, 1995). Formally anything can be made to look good or bad by being re-described; but in reality, some ‘truths’ are dominant than others.

The theorist of populist politics Ernesto Laclau (see Laclau and Mouffe, 1985; Laclau, 2005) argued that political reality – and to this extent ‘Truth’ – is largely the product of rhetorical discursive practices, the unstable result of which he characterises as hegemony. Truth does not have an existence outside such practices. Laclau’s approach is therefore useful for understanding both Brexit and the American presidential campaign, though it has limitations (which I will sketch out below). Laclau argues that political discourses are at their most effective when they establish ‘chains of equivalence’ between a range of seemingly disparate elements in ways that can mobilise the masses. The Occupy Movement brought a wide range of groups into the open signifier of the 99%. Yet this equivalence itself is grounded on a difference – we the 99% are not the 1% (see Bates, Ogilvie and Pole, 2016). For the Brexit campaign, the ‘person in the street’ is set against the European and metropolitan elites, ‘indigenous’ British people against migrants. Indeed, the biggest ‘success’ of UKIP is perhaps the way in which it was able to harness anti-migrant feeling to the Leave agenda.

What is particularly interesting in relation to both Brexit and the US election is that these relations of equivalence – as indeed Laclau’s approach elsewhere suggests – seemed to be entirely arbitrary. The JD Wetherspoon chain supported leave by setting out a range of criticisms of the IMF. A person in Lancashire voted leave because the local council lost his application for a parking permit. In the US, a Trump supporter claims that Barack Obama was responsible for 9/11.

How can political and social theorists in particular make sense of this?

We can see from the discussion above that the label ‘post-Truth’ is often used to denote two quite different propositions. I call these the everyday epistemological proposition and the radical proposition respectively.

In the everyday epistemological proposition, Truth tends to be reduced to ‘facticity’. A statement is said to be true to the extent that it corresponds to empirical immediacy (the economy is ‘growing’, ‘it is raining today’, ‘my train is five minutes late’, etc.). The opposite of ‘Truth’ is falsity. Falsity may simply be the result of empirical error; but it has a second key meaning – lying. The common claim – made by the Remain campaign and by critics of Trump alike – is that empirical error was reproduced as a result of the influence of more powerful lies. Accordingly, a post-truth politics is one in which the dominant practice is one of lying.

In the radical proposition, the post-‘Truth’ hypothesis does away with the categories of Truth and error. So, as we have seen, for Laclau, Truth is a product of unstable discursive practices. For Rorty, politics – as with ethics – is a practice of telling ‘sad and sentimental stories’ (see Rorty, 1989). Ultimately, the ontological grounding of politics is affect.

Rorty may be correct that our moral intuitions emerge from the manipulation of our emotions. Accordingly, poetry is possibly better suited to political practice than philosophy. However, I think that the everyday and radical claims are wrong-footed.

For what if a particular unconscious disavowal served to denote an underlying truth, a truth that reaches beyond mere facticity? What if the existential scream of the previously ddisenfranchised Brexit voter was an unconscious urge to destroy the neo-liberal stage of the European project, a project which completely subsumed human labour into the commodity form? For if the Brexit vote was the ‘estate vote’, then the abstract violence of the commodity form is felt more acutely in Burnley than it is Brighton.

The viscous irony of course is that this existential scream has come to be mobilised by those – such as the British Conservative MEP Daniel Hannan in the case of Brexit, and far right Republicans in the US case – who would let the market rip without constraint. This scream will not therefore produce a new freedom beyond neo-liberalism, but new and more brutal forms of exploitation and alienation.

Bibliography

Bates, D., Ogilvie, M., and Pole, E. (2016) ‘Occupy: In Theory and Practice’, Critical Discourse Studies, 13 (3). pp. 341-355.

Freedland, J. (13 May 2016) ‘Post-truth Politicians Such as Donald Trump and Boris Johnson are No Joke’.

Geras, N. (1995) Solidarity in the Conversation of Humankind: The Ungroundable Liberalism of Richard Rorty, London: Verso.

Marx, K. and Engels, F. (1845) The German Ideology.

Laclau, E., and Mouffe, C. (1985) Hegemony and Socialist Strategy, London: Verso.

Laclau, E. (2005) On Populist Reason, London: Verso.

Rorty, R. (1989) Contingency, Irony and Solidarity, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Politics

Politics Anna Vanaga

Anna Vanaga 1102

1102

Comment on “Post-Truth Politics?*”