By Dr. John FitzGibbon, Senior Lecturer in Politics

Few areas of European political science have grown at such a pace as that of Euroscepticism. Beginning with the work of Taggart (1998), a significant body of work has flourished all with the aim of seeking to understand opposition to European integration. The substantive academic literature that define the parameters of the study of Euroscepticism (Taggart: 1998; Sitter: 2001; Szczerbiak and Taggart: 2004; Kopecky and Mudde: 2004; Flood and Usherwood: 2005; Hooghe and Marks: 2007) were all drafted in a time of relative stability in the EU economy and politics of individual member states. The events of the economic and financial crisis that has gripped the EU since 2008 (henceforth referred to as the Eurocrisis), however, has brought a new dimension to the contestation of European integration. It is my belief that this ‘Euroscepticism’ is different to what has preceded in that it argues not for the return of sovereignty to individual member states (as Sinn Féin do in Ireland) or for withdrawal (as UKIP do in well the UK) but for substantial changes in the policy response of the EU to the Eurocrisis.

As Cas Mudde has discussed, in a very succinct and incisive account, the study of Euroscepticism has hitherto focused on either the extent to which a political actor wishes to remove their state from the processes of European integration (what he labels the Sussex School) or the ideological motivations for opposing the EU project (what he labels the North Carolina School). Euroscepticism has thus been interpreted by scholars (and to be fair politicians as well) as a zero/sum game whereby all criticism of the EU institutions and agreed EU policy is interpreted as Euroscepticism to a greater or lesser degree. The key word here is agreed. As EU policy is being formulated there is no doubting the deep divisions and angry confrontations between member state governments, Commission officials, relevant civil society members and MEPs. Once EU policy becomes agreed (meaning the position of the most recalcitrant voice has been brought on board), the policy ostensibly reflects the general will of all political and policy actors participating in the process. The slow but steady expansion of participants in the EU policy formulation process to include MEPs and certain civil society actors such as trade unionists, environmentalists and business organisations lends further credence to the perception that Euroscepticism can be characterised as the politics of extremists who are challenging the European social and political mainstream.

The Eurocrisis has radically affected the EU policy making process. What has emerged is a clear schism between the so-called prudent and solvent ‘Northern’ states and the supposedly feckless bankrupt ‘Southern’ states. This has fed into a clear policy divide with the ‘Northern’ states favouring ‘cuts to government spending, tax increases, and economic liberalisation to stimulate exports and raise economic competitiveness. This policy has come to be known as ‘austerity’ and has been strongly advocated principally by Germany, but also states such as Finland and Slovakia. The ‘Southern’ states disagree strongly with this policy. Instead they argue for an expansionist monetary policy from the ECB, the loosening of EMU deficit rules and increased EU spending to stimulate economic growth. Greece, France and Italy have been at the forefront in arguing for these changes.

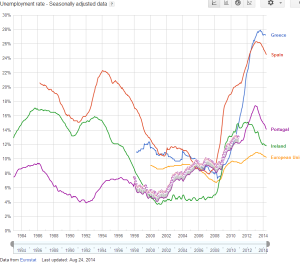

While it is not the place of this post to argue the rights or wrongs of various economic policies (there is plenty of that here) what is important to note is there is a clear ideological split in the EU, a division that is driven, in part, by strong public opinion toward EU issues. When the EU policy making process was focused on extremely low salient issues such as the system of CAP payments or tweaks to the Single Market, the public was simply not interested. Now that decisions at the EU level have direct and immediate impacts on their lives citizens have started to care about European politics and their political interlocutors are responding by contesting EU economic and financial policies at the national and European levels. This is true for both the ‘North’ and the ‘South’. In the ‘North’ citizens are concerned that the EU is forcing through direct transfers of their money to irresponsible governments in the ‘South’ while their state services are being cut back. While those in the ‘South’ are incandescent at the imposition of austerity and the failures of EU institutions to alleviate their eye-wateringly high unemployment rates.

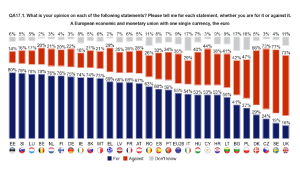

One would think that this would feed into outright rejection of the EU and the sweeping to power of Eurosceptic parties. Public opinion, however, tells a different tale. While citizens of the ‘South’ are deeply pessimistic about their current economic situation, they are still strongly supportive of membership of the Euro. I believe it is more correct to say that the EU is at a policy impasse rather than at risk of breaking up. Typically such impasses are decided by elections with the winner implementing their policy on the basis of democratic legitimacy. At the EU level, however, there is no such means of resolving the clash between the ‘North’ and the ‘South’ via a direct democratic process. Citizens who believe that their state should be a member of the EU, but who disagree with the policies being pursued by the EU, have no means of changing those policies. The attempt of the Europarties to launch such a process with their ‘Spitzenkandidaten’, and argument that the outcome of EP elections needed to have an impact on the EU policy, shows that there is a degree of recognition that this needs to happen. As of yet though, the European Council and the ECB have been extremely reluctant to open up their policy making process to greater democratic accountability. The belief is that such a process is against the European spirit of conscociationalism and too much of a challenge to member state sovereignty and the independence of the ECB.

They are too late. As Hooghe and Marks pointed out way back in 2007, in analysing the fallout of the Dutch and French No votes to the EU constitutional Treaty, the politicisation genie is out of the EU bottle. The Eurocrisis has increased this process exponentially. For scholars of opposition to European integration it demands the development of a new system of analysis for Euroscepticism. There is a clear need to disaggregate those that are opposed outright to the principle of European integration from those who oppose the current ‘austerity’ economic policies of the EU but who support membership. Otherwise we are left with an outdated categorisation that places the same label on the withdrawalist Dutch FPP of Geert Wilders as that of SYRIZA of Greece who want a radically reformed EMU.

With the development of the Spitzenkandidaten and the emergence of different alternatives for what policies the EU should take to end the Eurocrisis, the term Euroscepticism needs to be joined by others such as ‘Euroreformist’, ‘Euroalternativist’, ‘Critical Europeanist’ for example. Scholars must keep up with the pace of change in the EU.

(This post originally appeared on the excellent European Parties Elections and Referendums Network [EPERNN] blog: http://epern.wordpress.com/2014/09/16/pro-european-euroscepticism/)

Politics

Politics Anna Vanaga

Anna Vanaga 847

847