With the British Psychological Society – Social Psychology Section annual conference being held at Canterbury Christ Church this year, we thought it was a great opportunity for us to get together with our colleagues in Sociology and Psychology (obviously) and look at the interdisciplinary nature of our research. With the conference theme set as “the personal and the political in social psychology” the potential for different approaches to common issues was obvious. Dr. Nicola Abbott in Psychology suggested migration as an area with overlap between her work and that of Dr Lorena Arocha in Sociology, Drs Laura Cashman and John FitzGibbon in Politics, and Dr. Dennis Nigbur of Psychology, as suitable for an interdisciplinary panel.

All the papers provided a fascinating divergence of approaches to a single, ostensibly straightforward, topic. In turn they focused on migrant perceptions of social interaction; official language toward exploitation of migration and how it affects practice ; how patterns of bullying are different with migrant school children; and why Roma migration has increased populist behaviour among mainstream European political parties. What emerged from the panel was not that one paper had the ‘best’ methodology, insight or approach but that looking at an issue from a multi-disciplinary perspective provides a wonderful intellectual richness that leads to more questions, more ideas and more research.

Below are brief descriptions of the research presented.

Dr. Nicola Abbott

The number of young people seeking help for racist bullying increased sharply last year (ChildLine, 2013). This is not particularly surprising when one considers the heated public debate on the issue of immigration in the UK. One way of tackling this type of bullying in schools could be to encourage school peers to help come to the aid of someone being bullied based on their race. But in order to encourage peers to intervene, we need to understand what leads to this type of behaviour. Therefore, Nicola Abbott and Lindsey Cameron (2014) surveyed over 800 adolescents (12-13 years old) to find out if the level of contact with other racial groups is important.

They found that as opportunity for contact with different racial groups increased (e.g. at school and in their neighbourhood), so too did levels of empathy and cultural openness; which in turn, were associated with a greater intent to aid a victim of racist bullying. Finally, greater opportunity for contact with different racial groups, was linked to less of a preference for your own group (in-group bias). This was also then associated with a greater intent to aid a victim of racist bullying. These survey findings can help to design anti-bullying programmes that aim to increase empathy and cultural openness and decrease in-group bias, in order to encourage school peers to stand up for a victim of racist bullying.

Dr. Lorena Arocha

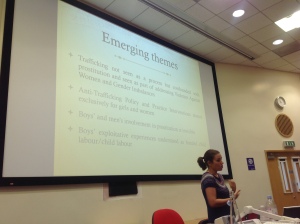

Over the last three decades, human trafficking has consolidated as a transnational social policy area (O’Connell Davidson, 2014), a problem to be recognised, identified and tackled. In 2014, we are marking a decade since the UN Trafficking Protocol came into force. Here, we look at the experiences of anti-trafficking interventions in two different countries, India and the UK. Based on qualitative research conducted in West Bengal in 2012 and in the South East of England in 2014 (ongoing), we examine policy and practice in two very different border regions.

Though in both contexts trafficking is framed and understood differently, unsurprisingly, the way in which it is framed has had a significant impact in how it is approached in practice. In both contexts anti-trafficking policy and practice have evolved in silos. Trafficking is confounded with prostitution and seen as part of addressing violence against women and gender imbalances in India. Anti-trafficking policy and practice interventions prioritise girls and women, rendering boys’ and men’s experiences of exploitation as something else (e.g. bonded labour). In the UK, trafficking is framed as a transnational organised crime and migration issues, and hence law enforcement and border control are the leading statutory agencies in anti-trafficking interventions. This has had implications in practice, as the identification of trafficked persons is different depending on their nationality (Anti-Trafficking Monitoring Group, 2010) and cases might not be investigated if they are not part of an organised crime group (e.g. domestic workers).

This analysis explores the anti-trafficking field not as a rescue industry (Agustin, 2007), but as a policy field, turning the focus onto policy and practice actors and the relationships among them and how these ensure the continuation of the anti-trafficking field but not so much the eradication of trafficking.

Dr. Laura Cashman and Dr. John FitzGibbon

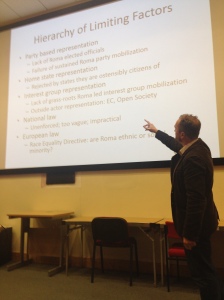

Prominent political figures from across Europe have engaged in Romaphobic discourse over the past few years. Specifically singling out a single group in society with a negative political narrative is associated with the radical right. Frequently such arguments are directed at Immigrants, Jews and Muslims and are considered ‘unacceptable’ by political actors who represented the mainstream in society. Why is it then that it is acceptable for such discourse to be directed at Roma and not other groups in society?

Our research incorporates a unique interdisciplinary approach between Roma studies and political party analysis. In taking this approach we are able to develop a model which describes how the specific nature of Roma as a group in society facilities their exploitation by political actors as part of a populist narrative. Despite the public and political actors having a clear idea of who the Roma are, in reality there is no agreed definition of what constitutes ‘Romaness’ amongst either scholars or the Roma themselves. This in turn negates the development of both political representation and legal protection for Roma. Other groups in society are more politically organised and are able to defend their interests more forcefully than the Roma. In conclusion we find that mainstream political actors engage in Romaphobia, despite it being against their ostensible societal values, because there are few negative consequences for them doing so.

Dr. Dennis Nigbur

This study aims to offer an individual perspective on acculturation – the process that happens when two or more cultural groups begin to live together. In addition to the socio-cultural adjustment at the level of the group, there are individual experiences and perspectives that deserve to be studied. Taking the migration experiences of international students as an example, this research uses phenomenological interview methods to find out how the acculturation process feels for the people involved in it.

The presentation focused on the perspective of Sachit, a postgraduate student who has already migrated twice for education purposes. The analysis of his interview data suggests that he sees migration as an individual decision and responsibility, and that the changes involved for him are pragmatic adaptations to a new social context. However, there remains an attachment to the culture, people and identity of his country of origin, which is experienced as helpful and nice to have. In Sachit’s account and in other interviews, you are the same person in both places, but you act – and, sometimes, feel – different.

The talk ended with a discussion of how international students hold a privileged position among migrants, but the methods used in this study could help examine the link between state policy and individual experience.

Politics

Politics Anna Vanaga

Anna Vanaga 760

760

Comment on “Bonding with our Psychology and Sociology colleagues at British Psychology Conference”