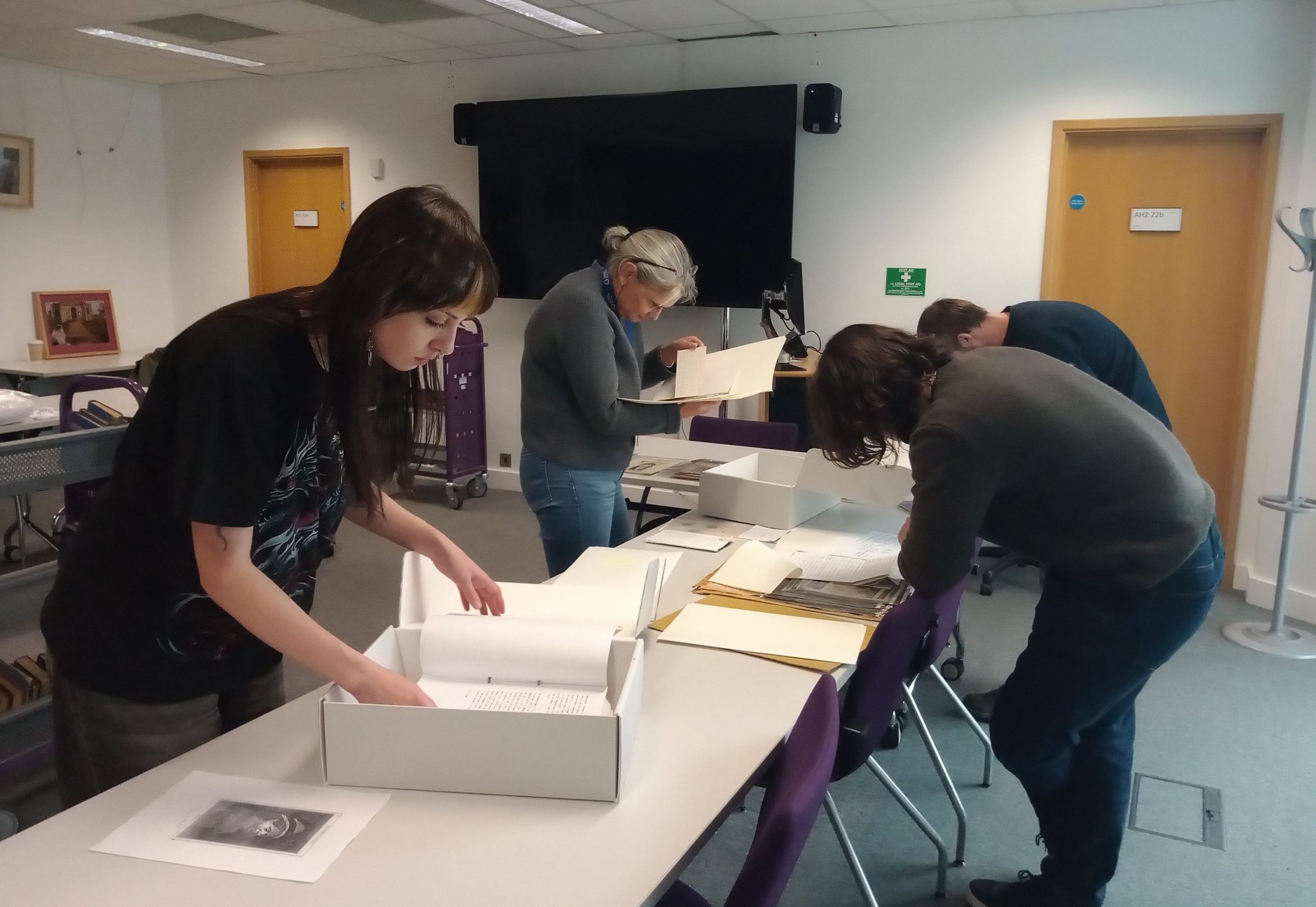

During Academic Development Week, the MA Heritage Students investigated the Hesba Stretton Collection as part of an archives and special collections workshop. Read on to find out what they discovered:

Who was Hesba Stretton?

Sarah Smith, more widely known by her pen name Hesba Stretton, was a prominent and bestselling Victorian author of evangelical children’s literature. She was born on 27 July 1823 at Church Stretton, Shropshire, the third daughter and fourth of eight children of Benjamin and Anne Smith. Her father was a bookseller, while her mother’s strong evangelical convictions profoundly influenced Sarah’s moral and religious themes in writing. In 1859, she struck up a friendship with Charles Dickens when her first story ‘The Lucky Leg’ was published in Household Words (‘Hesba Stretton’ 1911)

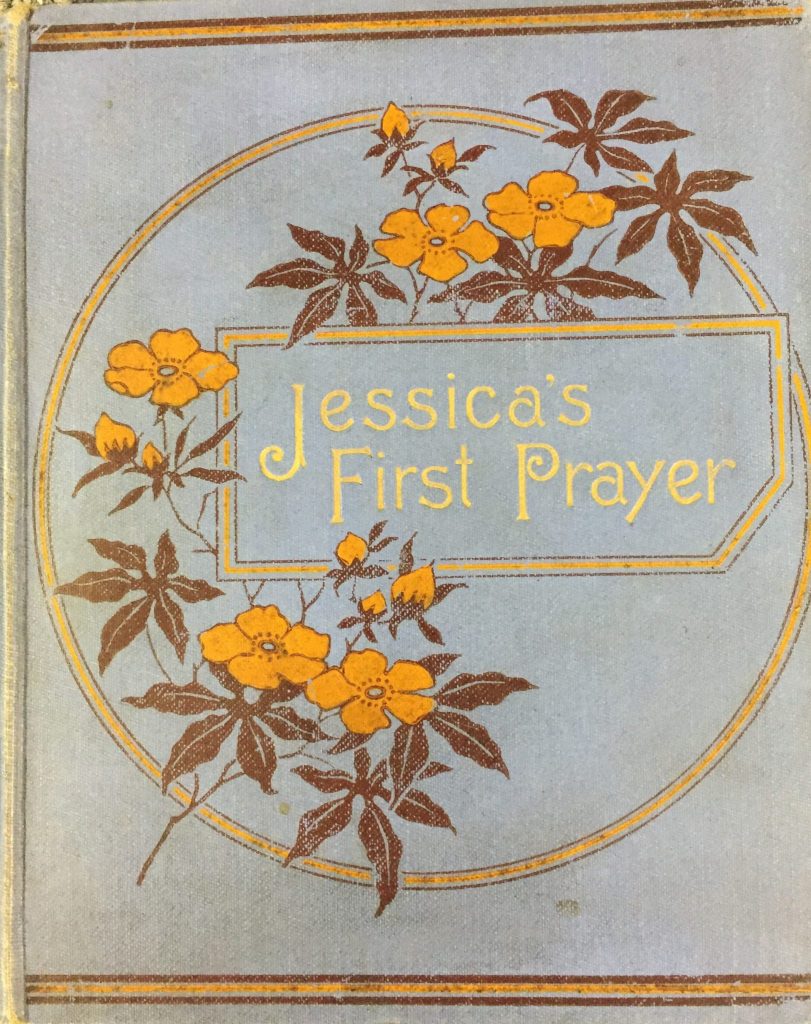

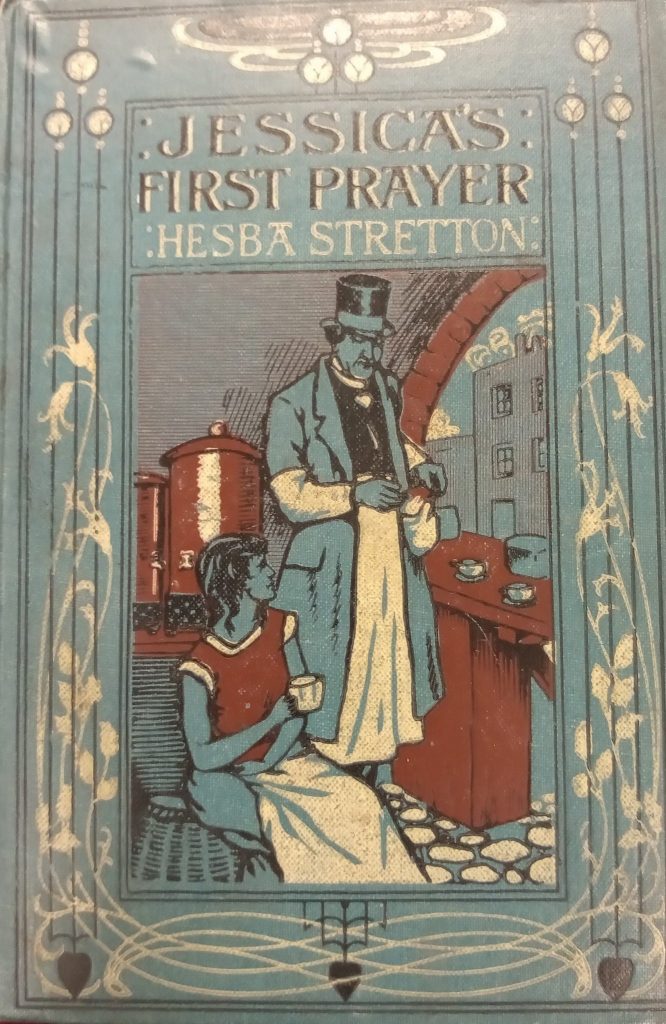

Jessica’s First Prayer

Stretton achieved critical acclaim with her first major work, Jessica’s First Prayer, which was published in 1866 as a serialized story in the London religious magazine Sunday at Home and later released as a book in 1867. The work became immensely popular, selling over half a million copies by the end of the nineteenth century (‘Hesba Stretton’ 1911), surpassing the sales of Alice in Wonderland, and firmly establishing Stretton’s reputation as a leading figure in Victorian children’s fiction (Alderson, 1974).

Copies of Jessica’s First Prayer from the library at Canterbury Christ Church University

Translated into other languages

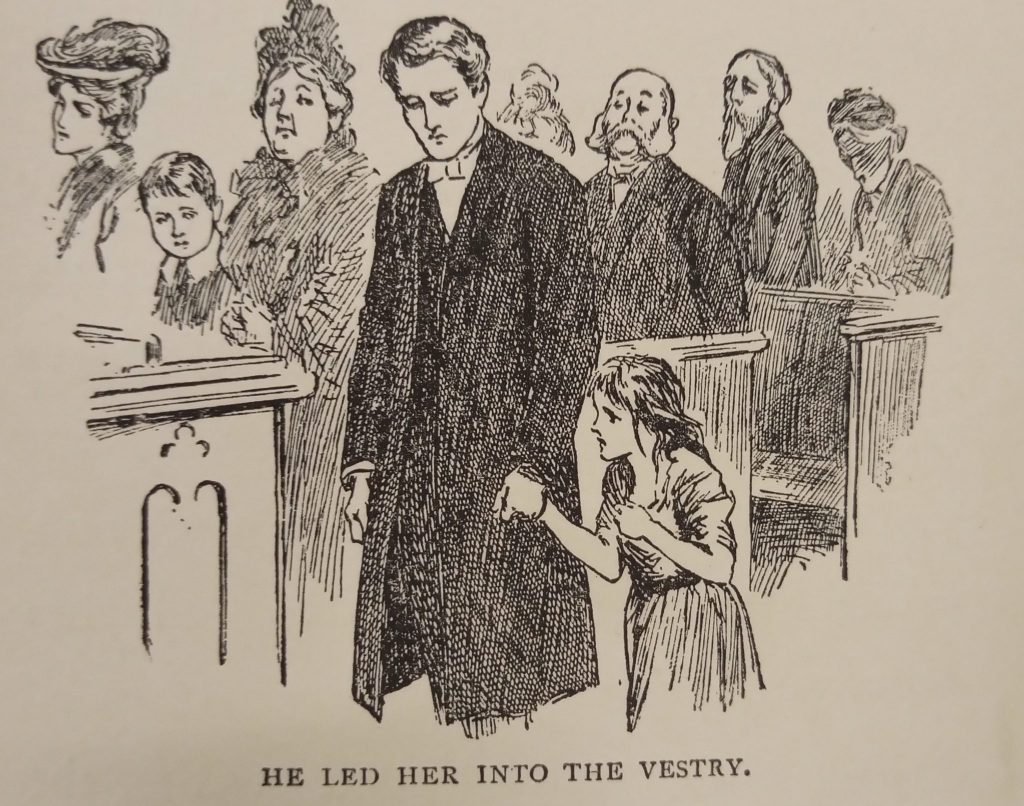

Alongside its popularity in the UK, Jessica’s First Prayer achieved international acclaim and was translated into every European language, and most African and Asiatic languages. The touching tale follows the story of a poor girl who is cared for by a coffee stall owner, who throughout the narrative learns of the importance of faith. It was met with immediate and long-lasting popularity, particularly in Russia, where the reading of this text was made compulsory in schools by Tsar Alexander II (Although this was revoked by his successor Alexander III who ordered the books to be burned) (‘Hesba Stretton’ 1911). Stretton’s heart-warming story instilled amongst Russian children a strong sense of Christian faith.

Depth of Christian Feeling

In both Russia and other parts of the world, Stretton was deeply beloved and hailed as an almost saintly figure. The Earl of Shaftesbury, in 1867, described Stretton’s work as ‘a beautiful story’ that would ‘hardly find a rival’ in its ‘nature, simplicity, pathos, and depth of Christian feeling.’ Although Jessica’s First Prayer was not Stretton’s personal favourite, it perfectly encapsulated her strong faith, background, and the charitable work she did to help those less fortunate than herself.

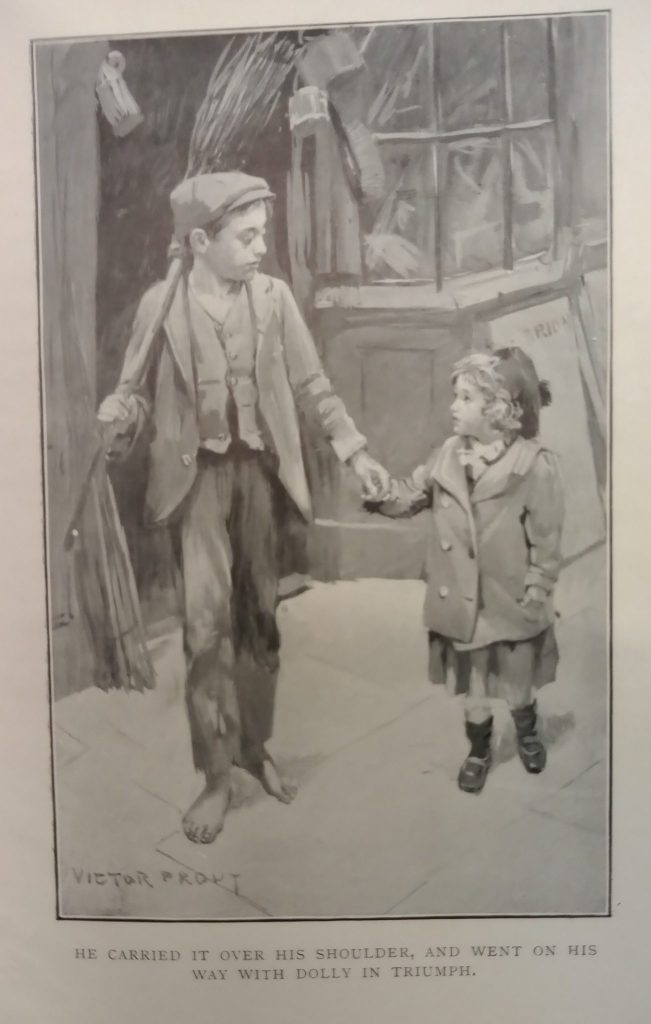

Illustrations from Jessica’s First Prayer showing the coffee stall owner leading Jessica into church for the first time and later in the book when she has been adopted and attends a service.

Passionate philanthropist

Alongside her successful writing career, Hesba Stretton was a passionate philanthropist. Her concern for poor children in particular was evident in many of her books, such as Alone in London (1869). In January 1884, Stretton wrote to The Times calling for the establishment of a society to prevent the ‘tyranny, oppression and neglect, suffered by helpless children’ and in another letter, written after visiting a children’s shelter in Liverpool, she begged that ‘the inarticulate cry of London children ought to be listened to; and will be listened to sooner or later’ adding the stark warning, ‘Only while we linger they perish.” (Stretton, 1884)

Stretton continued her letter writing campaign using strong emotive language influenced by her Christian upbringing: ‘The child Lazarus lies at our gate full of sores, seeking to be fed from the crumbs which fall from the rich man’s table. Shall we be less merciful to him than the dogs are? God forbid.’

Illustration from Alone in London where Tony and Dolly go to buy a broom.

Formation of the NSPCC

Hesba Stretton’s persistence, and that of other leading philanthropists such as Baroness Angela Burdett-Coutts, 1814-1906], paid off. In July 1884, the Reverend Benjamin Waugh founded the London Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. Five years later, the organisation changed its name to the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.

The collection

The CCCU collection contains 43 of Stretton’s novels as well as the research notes of novelist, Ann Purser, who kindly donated the material to the university. It will be of interest to researchers of Victorian children’s fiction, religious fiction or philanthropy. You can find out more on the Library Guide – Hesba Stretton – Canterbury Christ Church University

This article was written by Daisy Miloch and Amy Green.

References:

Alderson, B. (1974) ‘Tracts, reward and fairies: the Victorian contribution to children’s literature’, In Essays in the History of Publishing…, ed. Asa Briggs. Longman, p. 268

Stretton, Hesba (1884) ‘Cruelty to children’, The Times, 26 May, p. 6.

The Times (1911) ‘Hesba Stretton’, 10 October, p. 9.

Library

Library Michelle Crowther

Michelle Crowther 588

588