Where do you get your blog inspiration?

Sometimes I feel bereft of inspiration but sometimes it hits you when you’re least expecting it. I took February half term off work to look after the kids and on the Friday, to escape that week’s tropical storm, I took them to the Natural History Museum in London.

If you’ve taken young children to a museum in London during one of the busiest weeks of the year, you’ll probably have a picture of just how fraught my day was and I can’t say I was able to take in a great deal of the exhibits between the regular bouts of panic that one of the children had got lost among the crowd. One woman stood out to me though, a woman I’d never heard of but one I’d sung a familiar nursery rhyme or tongue twister about many times…

She sells sea-shells on the sea-shore.

The tongue twister, “She sells seashells by the seashore,” is based on a song written by Terry Sullivan.

The shells she sells are surely sea-shells!

So if she sells sea-shells on the sea-shore,

Then I’m sure she sells sea-shore shells!

Mary Anning or “the fossil woman” as the plaque said on the wall of the Natural History Museum, provided a number of the fossils we were looking at. In fact, she discovered one of the first full Ichthyosaurus skeletons, in the Blue Lias rocks of Charmouth beach… at the age of 11. I can’t say I’d managed much of note by that age so I was immediately intrigued to discover more about her…. so on my return to work, armed with trusty LibrarySearch (the University’s resource discovery tool) I set out to do so.

Stone Girl, Bone Girl

A quick search just under ‘Mary Anning‘ on LibrarySearch and I had 137 results to look through. I was pleased to see there were a couple of books in the Library’s Curriculum Resources collection. It was reassuring that Mary Anning might feature in the education of my children, particularly my daughter who already has a fascination for science and the natural world. When I mentioned to my daughter Samantha that Mary was only 11 when she discovered an Ichthyosaur, she was more than a little awe struck. I think I’ll get Stone Girl, Bone Girl out for her to read. You can find Curriculum Resources on the second floor of Augustine House.

For education students the article Mary Anning : She’s more than “Seller of sea shells at the seashore” by Renee M. Clary and James H. Wandersee provides great examples of how to introduce Mary Anning to school children. You’ll find it in The American Biology Teacher available through JSTOR.

To get a quick overview of Mary’s life I opened up her listing in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Mary was born on the 21 May 1799 in a seaside house in Lyme Regis, Dorset. To describe Mary’s childhood as eventful would seem to be a massive understatement. She was named after an elder sister who’d tragically been burnt to death in house fire in 1798. She was also the only survivor of a lightning strike that killed three other people in 1800 (Torrens 2008). What a remarkable start for a one year old!

Fossil Hunting

The author of Mary’s Oxford Dictionary of National Biography article was Hugh Torrens and that quickly led to an article by the same author Mary Anning (1799-1847) of Lyme; `the greatest fossilist the world ever knew’. You can find it in British Journal for the History of Science available through JSTOR. I continued to glean more about her early life…

Her father, Richard Anning, a cabinetmaker and carpenter by trade, used the mining of fossils to supplement his income. The local Jurassic coast was rich with finds and tourists to the fashionable Lyme Regis were more than willing to buy his finds. (Torrens 1995) Mary, along with her brother Joseph, would accompany her father on these hunts, it’s safe to say these early expeditions would shape her life.

The aforementioned Ichthyosaur was followed by numerous discoveries; including the first complete plesiosaur and the first British pterosaur skeleton (Torrens 2008). She discovered important fish fossils and that belemnite fossils contained fossilised ink sacs like those of modern cephalopods, like the octopus or squid. Her observations helped in the discovery that coprolites were in fact fossilised faeces. (Torrens 1995)

She sells sea shells on the seashore

In November 1810 Richard Anning died from a combination of Tuberculosis and injuries sustained from a cliff fall. (Torrens 1995) Mary was only 11 years old. A child who had to quickly grow up. He left the family with considerable debts and certainly no savings to dip into. The collecting and selling of fossils continued though, as a family run effort. Joseph, her brother reduced his involvement to take up an apprenticeship in upholstery and by 1825 at the latest, Mary had assumed control of the business.

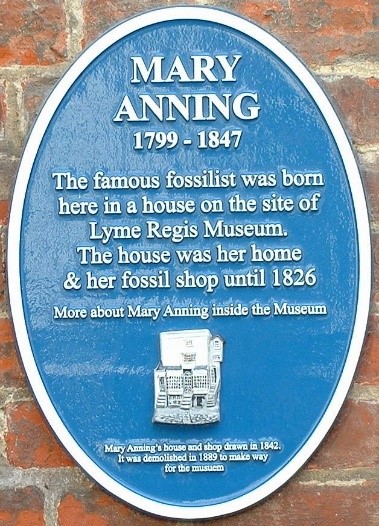

In 1826, at the age of 27, Anning had managed to save enough money to purchase a home with a glass store-front window for her shop. The shop was called Anning’s Fossil Depot. The building is now Lyme Regis Museum and you’ll find a blue plaque is on the wall to signify the building was Mary’s home and fossil shop.

Scientific recognition

The article The greatest fossilist the world ever knew: Mary Anning (1799-1847) by Michael A. Taylor published in the journal Endeavour, available through Science Direct was my next port of call. It ably highlights the barriers Anning faced as both a woman and working class in 19th Century England. Anning was an outsider to the scientific community. The Geological Society of London did not admit women and a subscription to the Society’s publications were certainly out of the reach to the working classes, costing a couple of months income (Taylor 1999).

Mary’s faith was also a barrier to success. Mary was what was know as a Dissenter belonging to an Independent Chapel on Coombe Street in Lyme Regis. These ‘Congregationalists’ outside the Church of England couldn’t legally marry or register the birth of a child in their own church. Dissenters were not allowed into universities or the army, and were excluded by law from several professions. If you’re interested in finding out more about Mary’s faith I recommend reading The Faith of a Fossilist: Mary Anning by Thomas W. Goodhue from the Journal of Anglican and Episcopal History. You can find it on JSTOR.

Ultimately, it was the rich gentleman who bought her fossils who got much of the credit for her discoveries. When they donated the finds to museums it was their name recorded for posterity. These gentlemen had new species named after them whereas Anning’s achievements were not recognised. (Taylor 1999) Museum records were bereft of Anning’s original involvement. Naturally Mary became resentful of this. Anna Pinney, a young woman who sometimes accompanied Anning while she collected, wrote:

“She says the world has used her ill … these men of learning have sucked her brains, and made a great deal of publishing works, of which she furnished the contents, while she derived none of the advantages.“

Anna Pinney, as recorded in McGowan, Christopher (2001), The Dragon Seekers, Perseus Publishing, pp. 203-204.

Fortunately, a combination of archival detective work and public interest has led to more and more of her accomplishments to be discovered and proper credit applied to her discoveries (Taylor 1999). More books are being written about Anning than ever and in 2010, one hundred and sixty three years after her death, the Royal Society included Anning in the list of the ten most influential women in British science history. Mary Anning is even due to be the subject of a feature film this year, Ammonite, starring Kate Winslet in the role of Mary.

Her name is only becoming more famous but the men who capitalised on her discoveries are all but forgotten.

That sounds like justice, long overdue.

…I can’t wait to tell Samantha more about her.

Need help?

If you need help making your own discoveries with LibrarySearch and Your Digital Library, you can book a 1-2-1 with your Learning & Research Librarians through Blackboard.

References

Anholt, L. (2000) Stone girl bone girl. London: Picture Corgi.

Clary, R.M. and Wandersee, J.H. (2006) ‘Mary Anning: She’s More than “Seller of Sea Shells at the Seashore”‘, The American Biology Teacher, 68(3), pp. 153-157. DOI: 10.2307/4451954

Goodhue, T.W. (2001) ‘The Faith of a Fossilist: Mary Anning’, Anglican and Episcopal History, 70(1), pp. 80-100. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42612156

McGowan C. (2001) The Dragon Seekers, Cambridge: Perseus Publishing.

Taylor, M.A. (1999) ‘The greatest fossilist the world ever knew: Mary Anning (1799–1847)’, Endeavour, 23(3), pp. 93-94. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-9327(99)01227-2

Torrens, H.S. (2008) ‘Anning, Mary (1799-1847)’ in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/568

Torrens, H.S. (1995) ‘Presidential Address: Mary Anning (1799-1847) of Lyme; ‘The Greatest Fossilist the World Ever Knew’, The British Journal for the History of Science, 28(3), pp. 257-284. Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/4027645

Library

Library Steve Peters

Steve Peters 901

901