The Matrix, a 1999 cyberpunk action film, is one of the greatest action films ever made, and one of the most important of late 90s/early 00s era. Written and directed by Lana and Lilly Wachowski, now two of the most famous transwomen in the film industry, its influence on popular culture remains pervasive even 24 years since its release.

On its face, The Matrix is simply a fantastic action film. But it has also been seen as a philosophical film and a trans allegory, and I’d like to explore all these angles as part of our Behind the Lens theme for LGBT+ History Month.

The premise

In The Matrix, the world we think we know is in fact a computer simulation (the titular “Matrix”) run to keep people pacified while machines use their bodies as a source of energy (it doesn’t make sense, but it really doesn’t matter). The true year is not 1999 (“the peak of human civilisation”), but closer to 2199, and the real world is now a dark wasteland as the result of a war between humans and the machines. A small number of humans have been “unplugged” from the Matrix and brought back into the real world, and our protagonist, Thomas Anderson, AKA “Neo” (Keanu Reeves) is the latest human to be unplugged. Morpheus (Laurence Fishburne) believes Neo to be a prophesied messianic figure known as “The One” who will set humanity free, if he can only fulfil his destiny.

None of this will seem particularly new. At its core, The Matrix is a “hero’s journey”i set in a well-trodden landscape. The idea of a simulated world has often been explored in both fictionii and philosophy.iii A post-apocalyptic future world has been a persistent feature of fiction ever since the Cold War. And a war between humans and machines in such a setting will be familiar to anyone who has seen The Terminator.iv

But that’s all OK. The premise is not what’s exciting about The Matrix. So, what is?

The action

Heavily inspired by martial arts films and anime,v the action of The Matrix is highly stylised: like a lucid dreamer, people who know they are in a simulation are no longer entirely bound by its physical laws.

Here’s a clip from the opening scene to give you a taste (you’ll need to sign in to Box of Broadcasts for access).

Here you can see examples of the two signatures of The Matrix’s action sequences.

The first is “wire fu” – the use of wires to allow for super-human, gravity-defying movement – facilitated by martial arts choreographer Yuen Woo-ping (also known for Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon).

The other is “bullet time”, a special effect where action appears to dramatically slow while the camera seemingly moves around the action at a normal speed. This effect was achieved using an array of cameras positioned around the subject, all firing almost simultaneously to create an illusion of near-instant movement around a point.

From Follow the White Rabbit (The Matrix DVD special feature). © Warner Home Video.

Wire fu and bullet time are blended with more traditional martial arts throughout the film to create some of the most recognisable action sequences in cinema, from the lobby shootout to the subway showdown. I’m tempted to include a lot of clips here, but anyone who anyone who doesn’t know these scenes should really just sit down and watch the whole thing.

The philosophy of The Matrix

Much has been made of the philosophical side of The Matrix. Whole booksvi and many journal articles have been written on the subject. Links have be drawn to the work of Plato, Descartes, Spinoza, and Nozick, among others, and analogies to various religions are easy to find. But the most explicit references to philosophy in the film are to Jean Baudrillard’s 1981 work Simulacra and Simulation.vii The cover of the book is shown in close up, and Morpheus introduces Neo to the desolation of the real world with the words “Welcome to the desert of the real”, pulled directly from Baudrillard’s opening paragraphs. The Wachowskis reportedly even asked members of the cast to read the book to help them better understand the film they were starring in.

Despite this, the philosophical side of The Matrix is often exaggerated. It’s certainly possible to find parallels with many philosophical and spiritual ideas in the film, but there is a bit of a scattergun approach. The authors of the book Matrix, Machine Philosophique see the film (as the book’s title suggests) as a “philosophical machine”, which does not so much carry a coherent philosophical thesis as introduce concepts for further exploration. Really, the film borrows from and combines various philosophical ideas, just as all media borrows from all kinds of narrative and artistic concepts.

The Matrix as a trans allegory

There has also been a lot of discussion of The Matrix as a trans allegory, especially since the Wachowskis came out as transwomen. In a 2020 interview, Lilly Wachowski affirmed this intepretation, but said that in 1999, “the world wasn’t quite ready for it”. Although it went unnoticed by many at first, there is certainly much in the film that can be easily interpreted as part of a trans theme.

Early in the film, when Neo is apprehended by the sinister “Agents”, he is accused of “living two lives”, one as the law-abiding and respectable Thomas Anderson, and the other as the hacker, Neo. Neo is the name the character goes by throughout the film: “Thomas Anderson” is simply the persona Neo uses to fit into society. Only the Agents – the computer programs tasked with protecting the Matrix – persist in the referring to Neo as “Mr Anderson”.

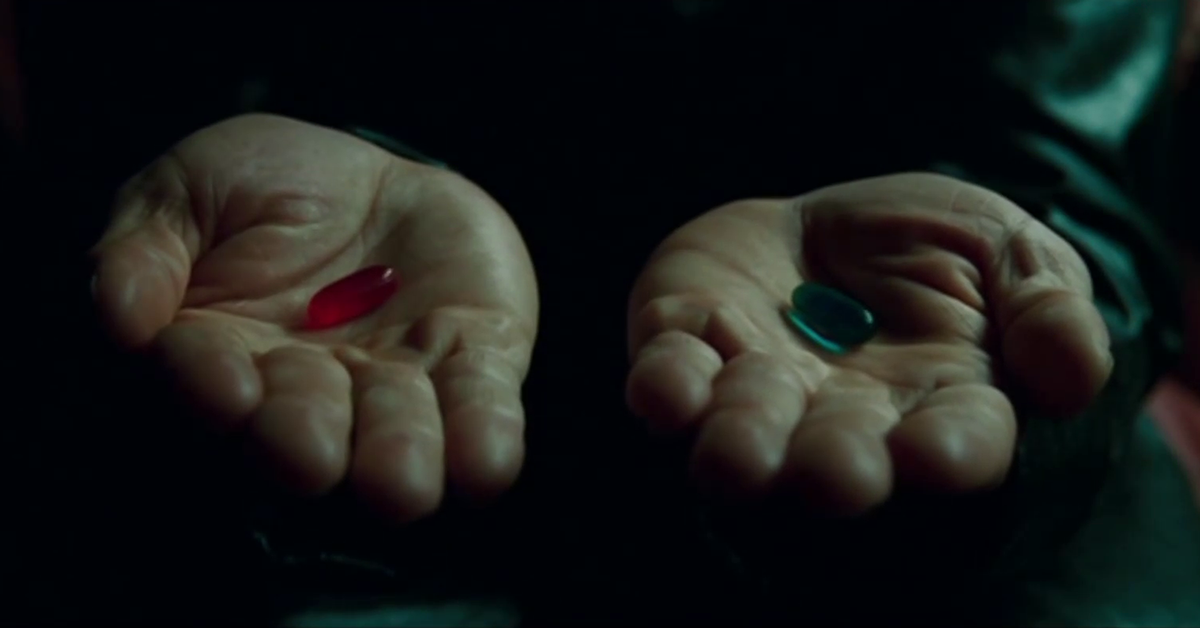

As the film progresses, it is explained that Neo has always felt something was not quite right with the world – he has a “splinter in (his) mind” – and he is given the option to remove himself from the artificial society of the Matrix altogether, becoming his true self not just in the seclusion of his own home, but permanently, in the real world. While this is in many ways liberating, the real world is clearly not an easy place to live in. But despite this, most of the characters clearly find living as their true selves preferable to the artificiality of the Matrix.

It’s easy to see the parallels to many trans experiences in a story about people who reject the false reality imposed upon them in a favour of a harder but truer life, or a person whose chosen name is continually rejected by the forces who aim to protect the status quo.

A more direct reference was originally intended for the film: one of Neo’s fellow “unplugged” humans, Switch, was envisaged as a character who presented as male in the real world, but in the simulated world, where a person’s appearance is drawn from their own mental projection of themselves, would be a woman. At the decision of Warner Bros, this idea was dropped, and in the final film the character is played by a single actor in both simulated world and the real world.

The final scene of the film features some particularly clear symbolism. As Neo promises “a world without rules and controls, without borders of boundaries”, we see a monochrome computer display, warning of a “system failure”:

As the camera moves forwards towards the text, our perspective is carried directly between “M” and “F” as the letters lose their rigid shape, blurring and taking on a more fluid aspect.

This symbolism is particularly interesting, because it went completely unnoticed by most people, but once you’re made aware of it, it’s impossible to miss.

The legacy of The Matrix

If the action of The Matrix all looks familiar, maybe even a little clichéd, that’s because the film was so influential that it spawned a host of imitators, along with a multitude of homages and parodies in the years after its release. To modern audiences, The Matrix may, at first glance, appear to be little more than just another of a crop of forgettable turn-of-the-millennium action films like Equilibrium or Underworld.

The effects, and the blending of Eastern and Western styles, are now almost commonplace in action films. But at the time of its release, the action of The Matrix felt new and exciting. In fact, it was impressive enough that the film beat Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace (a film with almost twice the budget) to win the 2000 Academy Award for Best Visual Effects.

The influence of The Matrix was much wider, however. Emily St. James summed it up in a Vox article:

Hollywood took notice, stealing everything from the costumes to the color palette … every element of it spread throughout the culture. The influence of anime became more pervasive, and comic book superheroes (the very rough template Neo is built atop) became the dominant cultural characters of our era. The Matrix didn’t invent any of these trends, but it drew a clear “before and after” line in the sand.

The Matrix also helped popularise the “simulation hypothesis”: the idea that we ourselves are living in a computer simulation. There is a very long history behind this concept, but today one of its most famous drivers is philosopher Nick Bostrom’s 2003 paper Are We Living in a Computer Simulation?viii This hypothesis continues to draw a considerable amount of interest today, and discussion of it continues to reference The Matrix as a way to draw in an audience who may be more comfortable with popular culture than musings published in Philosophical Quarterly.xi The term “Matrix defence” has even made its way into legal circles as a legal defence in which a defendant claims to believe they are living in a simulation.

Watching The Matrix

The Matrix is available through online streaming services, but you can also borrow one of our DVD copies, or watch it online for free through Box of Broadcasts. If you haven’t seen The Matrix before, I urge you to watch it. If you have seen it before, I urge you to watch it again.

i See Joseph Campbell’s book The Hero With a Thousand Faces, available from the Library in physical and e-book formats.

ii See, for example, Philip K Dick’s We Can Remember It for You Wholesale and the films based on it, both named Total Recall.

iii For example, Robert Nozick’s experience machine from Anarchy, State and Utopia.

iv The Terminator is available from the Library on DVD or through Box of Broadcasts.

v For example, Ghost in the Shell, available from the Library on DVD or through Box of Broadcasts.

vi E.g. The Matrix and Philosophy, available from the Library.

vii Simulacra and Simulation is available from the Library.

viii Bostrom’s paper is available online through the Library.

ix See, for the example, the documentary A Glitch in the Matrix.

Library

Library Ben Marchant

Ben Marchant 3624

3624