Chances are, if you see an example of Keith Haring’s work, you’ll find it instantly recognizable. His pop art style has become iconic, enduring the decades since his death, and his trademark bold outlines, simple, stylized shapes married with complex patterns, and vibrant colours feel as fresh and innovative now as they did in the 1980s. A prolific artist whose work consistently centred on raising public consciousness, Haring, his art, and his legacy truly embody LGBT History Month 2022’s theme of ‘Politics in Art’.

An early start with art

Born in 1958 in Reading, Pennsylvania, Haring was interested in art from childhood, spending time drawing with his father, an amateur cartoonist. After selling t-shirts featuring his own handmade designs while hitchhiking across the USA as a teenager, Haring went on to study commercial art for two years before dropping out to focus on his own creative work. Despite having lost interest in the creation of art for advertising purposes, the approaches and concepts behind this branch of art clearly made a lasting impression. Haring’s work is incredibly accessible and appealing to a wide range of audiences, and, as his fame, status, and popularity rose, he never lost sight of the importance of reaching as many people through his art as possible. When he opened his Pop Shop in New York in 1986, selling merchandise emblazoned with his designs, he was accused by some of selling out but Haring’s commitment to making his art accessible and affordable remained at the heart of his operations.

Urban legend

Following a stint working at the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts and then a move to New York to study painting at the School of Visual Arts, Haring had made a name for himself in the latter city and gained recognition as a prolific street and graffiti artist, adorning subways and lamp posts with his distinctive iconography. He saw the Pop Shop as an extension of the roots he had formed in his urban art, ‘breaking down the barriers between high and low art’ (Yarrow, 1990). While criticised by some for commercialising his output, Haring acknowledged that in actual fact, given his standing, he would generate more income if he made fewer paintings and sold them for higher prices. Personal profit was never at the top of his agenda.

The personal and political

This benevolent stance was further exemplified in his murals, which developed his graffiti designs into large-scale pieces of public art, many of which were voluntarily created for places such as schools and hospitals (Delistraty, 2017). One of the most notable of these, titled Crack is Wack, was created in 1986 and used Haring’s striking visuals to create a stark warning against the use of crack cocaine, which was ripping through low income and working-class neighbourhoods across the US (Ziv, 2016). His rise to fame during the 1980s was meteoric and he became a prominent member of New York’s artist community. In addition to various exhibitions, he collaborated with a number of other artists, fashion designers, and musicians, became a gleaming beacon of the city’s youth culture, and ‘partied as hard as he painted’ (Lutyens, 2001). Haring’s sexuality was central to much of his art, with many pieces being phallocentric. Some of these phalluses express a light-hearted and comical playfulness, tongue firmly in cheek, and some examine and dismantle patriarchal and oppressive power structures and dynamics. Social commentary certainly remains at the heart of much of his work. This core element is sometimes missed or disregarded, perhaps due to the accessible and inclusive nature of his designs, his bright colours and simple figures often conveying so much more than they appear to at first glance. He used his artistic voice to advance causes of justice, public information, and equality, and frequently expressed views at odds with a dominant patriarchal, heteronormative, racist, and capitalist society.

What would Jesus do?

In the early and mid-1980s, Haring created posters for distribution at demonstrations against nuclear arms and South African apartheid, and in his 1985 series of paintings, The Ten Commandments, Haring examined the oppression found within organised religion. As a teenager, Haring had been heavily involved in the Jesus Movement, a far-reaching and diverse group of evangelical Christians who promoted a wave of spiritual enthusiasm from the late 1960s to the late 1980s. They rejected materialism and the authority of the establishment, criticising the hypocrisy of the church and embracing the compassion and generosity found in the teachings of Jesus Christ, and Haring was heavily influenced by their activities and their message (Phillips, 2007). As a non-religious person myself who is aware of the homophobia that exists within certain sections of the church, I was quite pleasantly surprised to learn about this aspect of Keith Haring’s life. That he and other members of the Jesus Movement were able to identify with and commit to sharing the neighbourly love found within the New Testament, separate from the intolerance sometimes found within Christian institutions, is incredibly touching.

Silence = Death

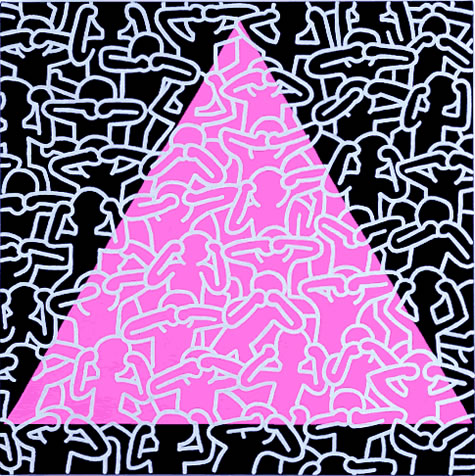

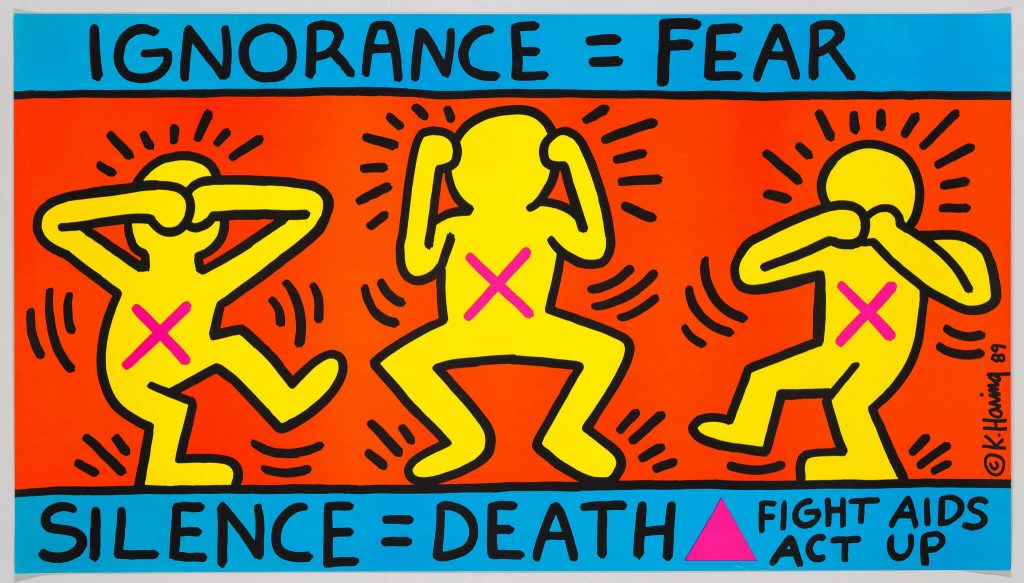

Though in Crack is Wack he may have expressed some common ground with Ronald Raegan’s government, who were waging their war on drugs, Haring was fiercely anti-Republican, a view that was cemented by Raegan’s refusal to acknowledge and act on the AIDS crisis that was engulfing the country and the globe. The US president was a very different kind of Christian to Haring and the chasm between the two men’s actions highlights the seemingly paradoxical nature of being a right-wing conservative while proclaiming oneself a follower of Jesus. Enraged by the homophobic Raegan administration’s callous disregard for the public health emergency that was taking lives at a terrifying pace, Haring created pieces that condemned this approach and promoted safe sex, emphasising the importance of action through adequate information, communication, and resourcing. As he so effectively put it, ‘Silence = Death’. Haring used such motifs as the pink triangle, a symbol used by the Nazis to identify gay men, and figures performing the actions of the famous ‘see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil’ proverb (Hoffman, Hou, Jones and Woo, 2020). He was unequivocal in his message: those in power who ignored the AIDS crisis and suppressed efforts to address it had blood on their hands.

The end of the world

In 1988 Haring was diagnosed with AIDS and he spent the last two years of his life raising awareness through his creative work and his activism with ACT UP, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, an advocacy group working to end the AIDS pandemic. For Haring, his personal circumstances and his politics were inextricable from his art, and he used his compassion and his rage to create striking visuals that are as impactful now as they were at the time of their creation. In Apocalypse, a collaboration with William S. Burroughs, a Beat Generation author whose work had been highly influential on the young artist, Haring draws parallels between the AIDS crisis and the end of the world, with the virus depicted using symbols of religious damnation and nuclear destruction (Huber, 2018).

A lasting legacy

Keith Haring passed away on 16th February in 1990 at the age of 31 from an AIDS-related illness. Before his death, he established the Keith Haring Foundation, which is devoted to providing education and opportunities for children and young people from disadvantaged backgrounds, and to the dissemination of public health information regarding HIV and AIDS. The progress that has been made in AIDS research and treatment in recent years is remarkable, and the outlook for those testing HIV positive or at risk of contracting the virus looks increasingly bright. HIV and AIDS are not specific to the LGBT+ community but were allowed to run rampant through these vulnerable populations as a result of prejudice and ignorance. The work and commitment of groups such as the Keith Haring Foundation has been vital in the achievement of such powerful progress and, while it is galling to imagine what might have been attained prior to this point in a society not shaped by such devastatingly erroneous and damning preconceptions, and we mourn the many, many lives senselessly lost, we must take comfort in how far we’ve come. The foundation website contains an extensive archive of information about Haring, images of his art, and details of the work being done in Haring’s name. Haring’s legacy is a powerful one; his art remains ubiquitous and synonymous with cool, and his philanthropy continues to enrich lives.

“There is nothing negative about a baby, ever”

– Keith Haring

One of the most enduring and well-known symbols created by Haring, and one of my personal favourite images from the rich catalogue of his work, is the Radiant Baby. The baby personifies purity and innocence but it is not helpless. It is full of life and light and joy and wonder, and it moves freely in a world full of possibility. The Radiant Baby is the childlike potential in all of us to be an independent, powerful and positive force and I find great comfort in it. There is huge sadness in the shortness of Keith Haring’s life, AIDS having robbed him, and us, of the years he might otherwise have spent continuing to deliver empathetic and educational messages through his art. But his prolific output lives on, as do his ideals and his desire to address injustice and change lives for the better.

References

Most of the electronic journal articles cited in this blog were found and can be accessed through CCCU’s LibrarySearch, our online catalogue. In addition, we also have a number of print books about Keith Haring, some of which are on display throughout February on the ground floor of Augustine House. If you would like to learn more about Keith Haring, take a look on LibrarySearch and see what you find.

- Delistraty, C. (2017) ‘Rescuing Keith Haring’s “Tower”‘, Modern Painters, vol. 29. no. 11, pp. 28.33.

- Hoffman, S. J., Hou, A., Jones, A. and Wou, J. (2020) ‘Learning from the role of art in political advocacy on HIV/AIDS’, Imaginations: Journal of Cross-Cultural Media Studies, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 233-258.

- Huber, L. R. (2018) ‘Pulling down the sky: envisioning the apocalypse with Keith Haring and William S. Burroughs’, CrossCurrents, vol. 68, no. 2, pp. 283-308.

- Lutyens, D. (23rd June 2001) ‘Thou shalt be a bit rude’, The Guardian, NP.

- Phillips, N. E. (2007) ‘The (radiant) Christ child: Keith Haring and the Jesus Movement’, American Art, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 54-73.

- Yarrow, A. L. (17th February 1990) ‘Keith Haring, artist, dies at 31; career began in subway graffiti’, The New York Times, p. 33.

- Ziv, S. (2016) ‘Haring, impaired’, Newsweek Global, vol. 167, no. 12, pp. 54-58.

Library

Library Emma Latham

Emma Latham 1146

1146