It has always struck me that being the first must take enormous courage. No one’s life follows a blueprint, but it is those rare miraculous individuals who can chart a course previously untraveled. How many of us have that conviction to be a true trailblazer? To be a true pioneer and pave a way for others to follow. Laurence Michael Dillon has been described as the world’s first transsexual man (Collins 2017) and was the first trans man to undergo phalloplasty. Armed with trusty LibrarySearch (The University’s resource discovery tool) and the Library’s wider Digital Library, I set out on a journey of discovery into the life of Michael Dillon.

Dum Spiro Spero

My first discovery in LibrarySearch proved to be a short piece from the British Journal of Psychiatry by Aidan Collins. Michael Dillon was born Laura Maud Dillon on 1st May 1954. Dillon was the second child of Robert Arthur Dillon and his Australian wife, Laura Maud McCliver. Robert Dillon was the heir to the baronetcy of Lismullen in County Meath, Ireland. The ancestral motto of the Dillons was Dum Spiro Spero – Whilst I breathe, I hope. Which proved a fitting motto for Michael’s life.

Collins mentions that Laura grew up in Folkestone but not the reason for this, so if I wanted to know more about Dillon’s childhood and explore this connection to Kent further, I would need to look elsewhere. When I am researching anyone for a blog or general interest, I always check for a listing in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. It contains over 60,000 biographies so is often a great place to start researching. Read our database guide to find out more or check out their LGBT History page.

I was pleased to find a biography for Michael Dillon written by Claire Taylor in 2004. However, what I read left me with a heavy heart. Dillon’s mother died giving birth to Laura. Her father, devastated, resentful, angry effectively disowned his children. The children were left in the care of two very strict Aunts who lived in Folkestone and saw their father once a year. The Kent connection unhappier than I could possibly have imagined. Laura’s childhood seemed very miserable. A self-described ‘dog’s life’. (Taylor 2004)

People thought I was a woman. But I wasn’t. I was just me.

In 1934, Laura Dillon started at St Anne’s College, Oxford. As well as studying, Dillon was a keen rower and became the President of the Oxford University Women’s Boat Club. It was at Oxford, Dillon started to describe the feeling of being ‘in the wrong body … People thought I was a woman. But I wasn’t. I was just me‘. An insightful quote from Liz Hodgkinson’s autobiography of Dillon, Michael, Née Laura, featured in Taylor’s article.

Upon leaving University Dillon found work in a laboratory near Bristol. The work involved the dissection of brains, something I could not imagine doing as a job in a million years, it did however spark an interest between the relationship of the body and the mind. In 1939, Dillon persuaded a doctor to prescribe testosterone, deepening Dillon’s voice, halting menstruation, and starting the growth of facial hair. Dillon left the laboratory as soon as the signs became obvious and started to identify as a man, choosing the name Michael. (Taylor 2004)

Michael’s life is hard to read about at this time. Lasting only a month in the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry and prevented from pursuing war work, Michael ended up spending four long miserable years as a petrol pump attendant. These sound like wilderness years, unable to fit in and just very lonely. It turns out it took a bizarre twist of fate, hospitalisation due to hypoglycaemia, that would lead to Michael back on the road to realise his dream.

Harold Gillies

It was whilst Michael was recovering in the Royal Infirmary, he came to the attention of one of the world’s few practitioners of plastic surgery. The surgeon performed a double mastectomy and provided Dillon with a doctor’s note that enabled him to change his birth certificate (which would prove to have unforeseen consequences later in life). He also put him in contact with the pioneering plastic surgeon Harold Gillies. (Taylor 2004)

Harold Gillies was a fascinating person to research as well. There are lots of starts in LibrarySearch if you would like to find out about this truly exceptional surgeon who has been described as the father of modern plastic surgery. He was fundamental in the development of a reconstructive surgery centre first in Aldershot, later moving to Queen Mary’s Hospital, Sidcup. (Battle 2004). The Centre was dedicated to reconstructive plastic surgery on the wounded coming back from the First World War. Gillies and his colleagues pioneered many techniques of plastic surgery; preforming thousands of operations. He was awarded the CBE in 1920 and an OBE for his efforts in 1930. (Battle 2004)

I’m getting off track though… Gillies performed at least 13 surgeries on Dillon between 1946 – 1949. Phalloplasty wasn’t unknown. Gillies himself had reconstructed penises for injured soldiers or intersex people with ambiguous genitalia. This was the first time a trans man had undergone phalloplasty though and it had to be done under the guise of surgery for the condition hypospadias (Taylor 2004). It’s hard to imagine how hard going through 13 surgeries must have been for Dillon from both a mental and physical point of view. At one point a noticeable limp had to be passed off as a war wound flaring up. Pioneering new techniques could not have been easy but Dillon’s sheer perseverance I find incredibly inspiring.

Roberta Cowell

In 1946 Dillon published the book Self: A Study in Ethics and Endocrinology, a book about what would now be called transsexualism, though that term would not be introduced into the English language until 1949, based on Magnus Hirschfeld’s coinage (in German) of the term “Transsexualismus” in 1923. I’ve written a blog about Magnus Hirschfeld if you want to find out more.

The year after the completion of his surgery, Michael Dillon fell in love. His book had brought him to the attention of Roberta (born Robert) Cowell. Cowell was a famous racing driver, who would become the first British trans woman to receive male-to-female sex reassignment surgery. Though Dillon was not yet a licensed physician, he himself performed an orchidectomy on Cowell which was illegal by British law. Cowell’s vaginoplasty was later performed by Gillies (Taylor 2004). As besotted as Dillon was, his affection was spurned by Cowell. Cowell would return to race cars again. Pathe News have shared the following clip of her comeback 1957 hill climb race on YouTube.

To find out more about Dillon and Cowell’s relationship I highly recommend the Channel 4 documentary The Sex Change Spitfire Ace. You can access if through Box of Broadcasts here https://learningonscreen.ac.uk/ondemand/index.php/prog/0B550D5B?bcast=124496613. To find out more about Box of Broadcast read our guide.

Later life and Buddhism

After qualifying from medical school in 1951, Dillon became a ships doctor. This suited his hope of acceptance and keeping a relatively low-profile life. This was shattered by a simple mistake, as his own aristocratic past came back to haunt him.

Michael produced his amended birth certificate to Debrett’s, a publication that listed all the aristocratic titles and the current lines of inheritance. In 1958 Dillon was listed as the next male in line for the baronetcy at Lismullen. This brought to light a discrepancy between the Debrett’s version and Burke’s Peerage and led to a scandal in the press. You can read the Time magazine article from the 26 May 1958 online and read how the “newsmen” tracked down the “Bearded, pipe-smoking Dr. Dillon” in Philadelphia ” aboard the British freighter, City of Bath, on which he serves as medical officer“. It seems being hounded by the press was as common in the 1950s as it is today.

Michael fled, his hopes for relative anonymity on board ship in tatters. He escaped to India where he spent the rest of his life. He first lived at an English Buddhist monastery in Kalimpong, then moved to Sarnath, where he attended the Sanskrit University in 1959. He later lived at Rizong monastery in Ladakh, as a novice monk. He took the name of Jivaka (doctor), and was the first westerner to be ordained in the Tibetan order.(Taylor 2004)

Michael’s final years ended as his childhood began. More ‘dog’s years’ ahead. His hopes of finding some sort of spiritual enlightenment were not within his grasp. He couldn’t adjust to the Tibetan diet and had no money to buy alternative food. He literally starved and became emaciated. (Taylor 2004)

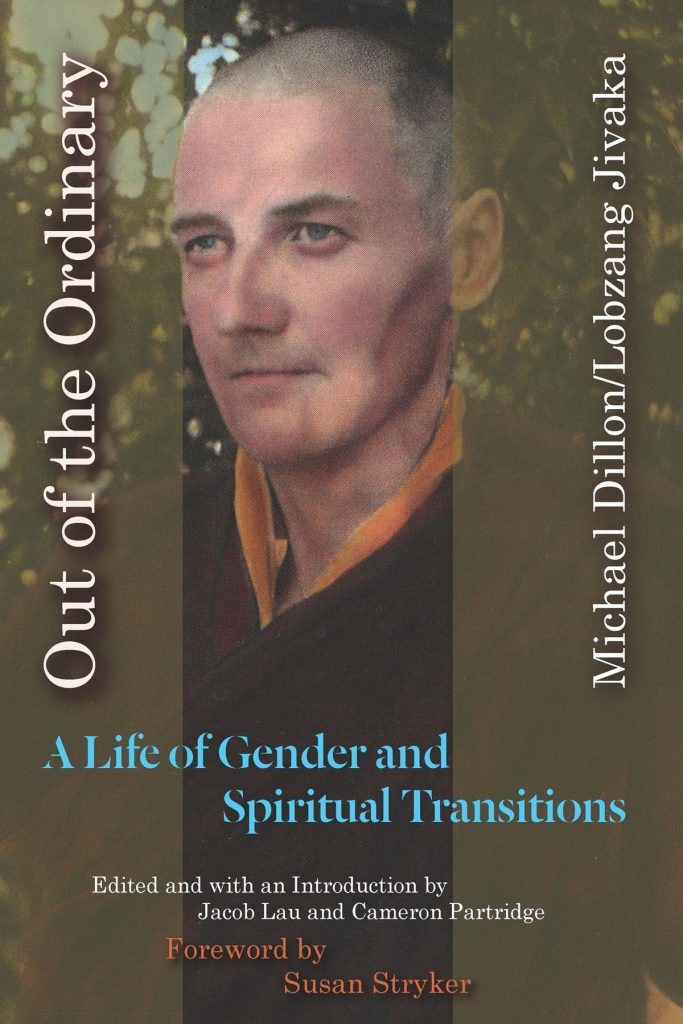

A legacy lives on

Michael Dillon died on 15 May 1962 in the Civil Hospital in Dalhousie. He was 47 years old. After his death, his agent received a manuscript of his autobiography which was completed two weeks before Michael’s death. (Taylor 2004). Dillon’s hopes for his remarkable life to be shared with the world would eventually come to fruition. It was published as Out of the Ordinary: A Life of Gender and Spiritual Transitions in November 2016.

Over 50 years later.

His hopes finally realised long after his final breath. His hopes though realised so much more for others. With the help of Gillies he’d successfully forged a path many others would follow.

Dum Spiro Spero

References

Battle R. (2004) ‘Gillies, Sir Harold Delf (1882–1960)’, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/33407 (Accessed: 3 February 2021)

British Pathé (2014) Roberta wins Hill Climb (1957). Available at https://youtu.be/CQ0MENnadk0 (Accessed: 9 February 2021)

Collins, A. (2017) ‘Laurence Michael Dillon of Lismullen: world’s first transsexual man’, The British Journal of Psychiatry, 210 (3), pp. 179.

doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.196642

LGBT History Month (2021) 2021.04 – The Faces For 2021: Michael Dillon. Available at https://youtu.be/KIGYHyjuBBU (Accessed: 9 February 2021)

Taylor, C. L. (2004) ‘Dillon, (Laurence) Michael (1915–1962)’, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/76743 (Accessed: 3 February 2021)

‘The Sex Change Spitfire Ace’ (2017) Channel 4. Available at Box of Broadcasts. (Accessed: 3 February 2021).

Time Magazine (1958) GREAT BRITAIN: A Change of Heir. Available at http://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,936913,00.html (Accessed: 9 February 2021)

Library

Library Steve Peters

Steve Peters 1615

1615